Recently I came to learn that the number one sport in America is not baseball, not basketball or football, not even my beloved figure skating, but birding! That’s what the Audubon website claims, as it says, breathlessly, “Did you know that birding is the number one sport in America? According to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, there are currently 51.3 million birders in the United States alone, and this number continues to grow!”

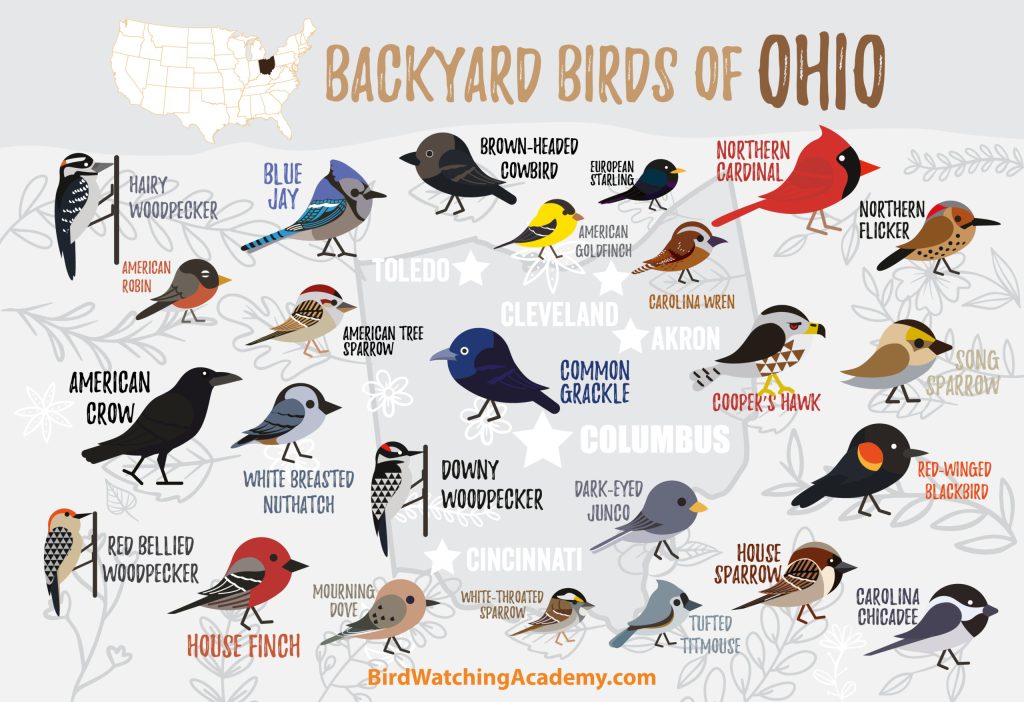

Birding. As in, becoming knowledgeable about knowing where to look for birds, what to look for, and what to listen for. Is it a woodpecker you’re seeing, or a blue jay? A house sparrow, or a mourning dove, or a dark-eyed junco, or a carolina chickadee? Each of these names is a verbal label, telling you where the bird is typically found, what its distinguishing physical marks are, and what its signature song is.

Birding, says the Audubon website, brings a sense of wonder, and it is just fun.

Who are some of the birders among us this morning?

Learning about birding was inspiring to me and, given the diversity of birds existing, I found myself thinking about yet another kind of diversity which is often on my mind: our Unitarian Universalist diversity. I found myself imagining that you and I are just like the fine feathered friends whom birders love to seek out.

Maybe right now, you might pull out your imaginary binoculars. Pull them out, and train them upon another person in this space. Ask, What kind of fine feathered friend are you? Where do you typically hang out? What are your distinguishing characteristics and behaviors? What is your signature song?

In this religious habitat, we are a unity-in-diversity. And we love our diversity.

One aspect of this relates to where we fine feathered friends tend to congregate. Where we typically congregate says something about our spiritual priorities and commitments. If we are most often to be found in the choir loft, or in an Aesthetics Team meeting, for example, it suggests that beauty is a spiritual value to us and we want to help make more of it. Or, what if most often we are found in a religious education classroom or space? That says something about our belief in the value of the lifelong journey of learning and growth, and we participate either as teachers or learners. Perhaps we are most often found in justice-related events and activities, some of which happen beyond these walls. That suggests something about how we prioritize transformation in ourselves and the larger world–our sensitivity to oppression and our thirst for liberation. And, if most often we are found in a Board meeting, a Coordinating Team meeting, or some other committee space, well, that says we are committed to a spirituality of democratic action. Stuff around here just doesn’t materialize on its own!

All of these differing spiritual priorities and commitments matter. This is good diversity, and we need it all!

Next, there’s the kind of diversity which relates to the question of what to look for. In traditional birding, you look for distinguishing physical features: color variations, variations in size and shape, variations also in behavior, as in, is the bird acting alone or in a group? Is it stalking, standing still, or flitting about? Apply this to humans, and what we’re talking about is culture and ethnicity. Let’s define these terms. Culture: A set of shared ideas, customs, traditions, beliefs, and practices shared by a group of people that is constantly changing, in subtle and major ways. Ethnicity: A group of people who identify with one another based on shared culture. The five main world cultures are Asian, African, European, Middle Eastern, and Latin American. The six main ethnicities in the United States are White, Hispanic, Black, Asian American, Native American, and multi-ethnic American. This aspect of our West Shore diversity is extremely interesting, and I can only acknowledge it here in passing. My sermon on Sept. 17 will address it directly, as it touches upon our worship; and I also suggest that you check out our Undoing Oppressions group, which regularly explores issues around race and other oppressions. You might also consider attending the Class Aware religious education course which begins in early October. This course focuses on class issues in congregational life. Very important.

With this dimension of diversity, what’s at stake is becoming aware of the diversity of cultures and ethnicities that already exists at West Shore and exploring ways to expand on that, uncovering ways we stymie it, and just becoming more authentically multicultural.

And now we look to a third aspect of our Unitarian Universalist diversity, which will be our main focus today. Our theological diversity. For traditional birders, this would be analogous to listening for a bird’s signature song. What are the diverse theological songs we sing?

Right here, we have one of the uniquely distinguishing features of our religion. Our religious way welcomes theological diversity, and that’s unique! Woodpecker theology belongs just as much as blue jay theology or house sparrow theology or mourning dove theology, and so on. So what if dark-eyed junco theology says that the Bible has important things to say, and carolina chickadee theology says that the Bible is optional and that there may be better sources of wisdom. Our church believes that “you don’t have to think alike to love alike.”Dark-eyed juncos and carolina chickadees can coexist in peace, within these walls, if both abide by our behavioral covenant of mutual respect.

It is glorious.

And, a Unitarian Universalist can get so used to this that the reality in most other religions fades into the background. Too many other religions say: there can only be one theological way, and all the others ways are wrong. In too many religions, religious communities are single-species habitats only. Many Christian churches, for example, hold to very specific beliefs about God, Jesus, and the Bible, and the only kind of birds that are going to feel welcome at those churches are the fine feathered friends that flock to such beliefs, and never stray.

So, today, I want us to bring renewed awareness to what we can easily take for granted about our Unitarian Universalist spiritual habitat, which is our glory. When all we fine feathered friends are in shared space together, I want us to pull out our binoculars and look at each other with a renewed sense of theological wonder. Pull out those imaginary binoculars, again. Train them upon some other person in this space. Ask, What kind of fine feathered friend are you? without taking for granted that they necessarily believe the same things you do about God, Jesus, the Bible, and the myriad of other religious things there are to believe in.

Here’s a quick quiz, to prompt a raised awareness about the many varieties of God-related belief among us. There is, of course, so much to theology beyond this, but the question of God never fails to generate a lot of diverse ideas and theories.

The quiz: I will name a series of possible sermon topics, and your gut response will indicate what kind of theological bird you are:

1. God the Noun–as in, the God of traditional Christian theism, who is an omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent Person. Perhaps One Person, perhaps One-In-Three and Three-In-One.

How does that settle with you? Or what about this sermon topic:

2. God the Verb–as in, a nontraditional view of God, a Process Theology God (or, equally, Goddess) whose body is literally the changing, evolving physical universe and whose spirit is the Divine Spark within each of us, the Still Small Voice which encourages us to persist through all trials: to love, to fight against social oppression, to find joy, to become whole. The technical theological label here is Panentheism. Some versions of Paganism also go here.

Or what about this topic:

3. Gods Aplenty–as in, a polytheistic view of ultimate reality, in which there are many Gods and Goddesses who each have jurisdiction over specific aspects of nature, who each command respect from humans, and to which humans can turn for special gifts and graces. Other versions of Paganism go here.

Or what about this:

4. God the Adjective–as in, a mystic view of reality which may be agnostic about God being like a Person per se…. Here, the belief is in the possibility of moments in life where you have a felt sense of Oneness with the Universe. God here is more a quality of experience, rather than an independent divine consciousness. Another label for this viewpoint is Animism or Pantheism. Buddhism could fit in here as well, with some tweaks.

And then there is this possible sermon topic:

5. God as Energy–as in, God is like the Force in the movie Star Wars, or God is the chi energy that Taoism speaks of. This sort of God is an energy that humans can learn to mobilize. People who practice Witchcraft mobilize life energy with the highest of intent, and they affirm what’s called the Rule of Three, which says, whatever energy is put out into the world by a person, that energy will be returned to that person three times.

But what about this sermon topic?

6. God the Expletive–as in, God is a human creation meant to empower the ruling classes with a powerful weapon, enabling them to maintain their rule over the underclass. Karl Marx would say that this God simultaneously serves the underclass in that it is an “opiate of the people”–the thought of happiness in an afterlife makes people more complacent and willing to go along with injustice in this life. One possible label for this is Atheism, or Marxism.

And then, of course, there’s this topic:

7. Too Confused to Decide–as in, there’s not enough evidence for or against the truth of any of these ideas. Call this Agnosticism.

And then, this:

8. Pieces and Parts–as in, there are parts in many or all of the above perspectives that are valid, based on the situation one is in, or how one defines this or that term. Call this Spiritual Eclecticism.

Eight possible sermon topics on God, and trust me, there’s plenty of possible others.

Which sermon would you flock to? Which sermon would startle you?

And, my fine feathered friends, you are all welcome. As your minister, my Unitarian Universalist promise to you is that I will respect the various theological perspectives and rotate among them. Every bird will have its day in this space, as far as is humanly possible and there is time enough.

Our theological diversity is what makes us astonishingly different from so many other religions in the world. It really is our glory.

However, what if I were to tell you that this glory can also, potentially, be our downfall? Freedom isn’t easy. Freedom to be theologically diverse in community can, under certain circumstances, stunt spiritual growth. It is a paradox. Let’s take a closer look at this, for the rest of our time together.

There are two potential dangers to name, and both are lifted up in an official UUA denominational report from 2005, entitled Engaging Our Theological Diversity. One has to do with what the report calls “the culture of niceness,” where people become afraid of offending one another. We are afraid to speak about the things that theologically matter to us because it might turn off others who believe differently. “Encouragement to spiritual growth,” says the Engaging Our Theological Diversity report, “is a stated goal of congregational life in the UUA’s Principles, and the rich theological milieu present in most of our congregations would seem to be fertile soil for such growth; but if people are afraid to talk about and experience the diversity before them, then the potential for growth will be stunted.”

How terrible for this to happen, especially when our theological diversity is our glory! How ironic!

Especially ironic, when you come to learn something that the great transpersonal psychologist Abraham Maslow came to learn through his research. Maslow is the guy who coined the phrase “peak experience.” Peak experience is like a God-the-adjective-moment, which is a profound moment of love, understanding, happiness, or rapture, during which a person feels more whole, alive, self-sufficient and yet a part of the world; more aware of truth, justice, harmony, and goodness. Maslow tells us that when his students began to talk to each other about their peak experiences, they began having them all the time. It was as if the simple act of being reminded of their existence triggered more of them. What I am saying is that when we talk about our deepest spiritual moments, it makes it more likely that more people will have more of such moments. Conversely, if we do not talk about such things, we may block their happening.

Theological silence stifles the spirit. Let’s not allow a culture of niceness to divert us from our purpose as a church. Replace a culture of niceness with a culture of covenant-centeredness in which healthy behavior expectations are laid out, and there is honest acknowledgement that disagreement will happen, but “we need not think alike to love alike!”

My own suspicion is that the culture of niceness squelches us and theological silence descends like a pea-soup fog upon us because we don’t fully appreciate the unique role of beliefs in Unitarian Universalist religion. Many other religions see holding the right beliefs as the be-all and end-all of faith, and if we unconsciously import this idea into our UU communities, then, yes, theological differences can raise a lot of anxiety and can lead to mutual contempt and shaming. But we must bring this unconscious mistake to light. Beliefs are NOT the be-all and end-all to our Unitarian Universalist religion. Our Unitarian Universalist religion is supposed to be a way of the creative unfolding of the Self (not the ego), in which beliefs serve only as stepping stones to further growth. You have to start somewhere. So you start with beliefs that make the most sense to you at the time. But, over the course of experience, whenever your beliefs prove to be limited or limiting (say, in the face of further reflection and research, or in the face of a life transition or crisis), you exchange them for other beliefs that are more life-affirming. Beliefs are not the ultimate goal of the UU religion; they are a means to the goal–the goal being quality of life: integrity, justice-seeking in one’s living, capacity to grieve, capacity to feel joy, aliveness.

In this light, when you happen to be in a conversation and you come to realize that the fine feathered friend across from you holds a theological point of view that maybe you once held but discarded long ago–or maybe you just dislike it–well, be more generous. Let them be who they are. Let them have their journey. Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle, and none of that battle may be visible to you. Judge not lest you be judged.

Be more generous. This is also the solution to the second and last danger in our diversity: diversity in how people come to be Unitarian Universalist in the first place. Says the Engaging Our Theological Diversity report, “Today, Unitarian Universalism is predominantly a faith of ‘come-inners,’ those who joined the church as adults, with a minority of ‘born-inners,’ those who were born or grew up as UUs. We may come from the faith tradition of our childhood, or we may come from no faith tradition at all. Most of us have in common, however, the experience of being raised in a tradition other than Unitarian Universalism. Stories abound of UU congregants saying, ‘I was always a Unitarian Universalist, but didn’t know it,’ or ‘I finally found a church community where I could express my beliefs and have them accepted.’ Gatherings of newcomers express joy at finding a community of like-minded people. At the same time, there are some substantial differences between the ‘come-inners’ and ‘born-inners’ among us, differences that are potential sources of tension and conflict.”

How many of us fine feather friends here today would consider themselves “come-inners”? You came to this faith from elsewhere? But this category contains its own diversity. Some come-inners come inside bearing the scars of previous bad religious experiences. The primary thing they might want to do with their new-found freedom is do the thing they were never able to do in their previous church: to push back against authority; to be skeptical; to not have to engage God, Jesus, and the Bible because in their old church those things proved toxic. Typically, this kind of come-inner may not be able to tell you what they believe, but they will have little difficulty denouncing what they do not believe. Often they are Unitarian Universalists largely for negative reasons–because this faith accepts their doubts and does not demand that they meet some imposed external standard.

Contrast this to another kind of come-inner: the kind that comes inside bearing no scars, and they may be open to exactly the sorts of things that the other kind of come-inners are trying to escape! God, Jesus, and the Bible? Zen, Taoism, New Age channeling? Prayer, meditation, chanting, Zentangle? It’s all good! Let’s try it all! Let’s see where it goes….

As for the fine feathered friends among us who are “born-inners”–who are you among us? You are second, third, fourth generation UUs, and here’s what the the Engaging Our Theological Diversity report says about you, starting with a contrast: “For many newcomers, the experience of finding Unitarian Universalism is intoxicating enough; for someone from an oppressive background, it is wonderful to find a place where questions are welcomed and where nobody is cast out for believing the wrong thing. But for someone who grows up in the faith, the permission to question all matters of belief is not an earthshaking revelation—it is simply the way things are. Born-inner UUs are often interested in exploring Unitarian Universalism and spirituality more deeply, but sometimes they cannot find a place for such exploration in the adult congregation.” Yes, that’s right–for them and for come-inners who aren’t escaping previous religious oppression. Often, our churches can cater to those who are spiritually wounded and who really do need to be in rejection mode for a time as part of their recovery. Combine this with a culture of niceness, and the Unitarian Universalist church, whose glory is supposed to be its theological diversity and freedom, can find itself locked in a pattern of avoiding anything that is spiritually rich. It will avoid all words and all the rituals and all the songs and all the anythings which, for just some members (or, for different members at different times) cause angst. In service to the goal of being as nonoffensive to the people who carry the most spiritual scars, the church essentially becomes like a meal of hospital food: so-so nourishing, and bland as bland can be.

Don’t get me wrong. Spiritual abuse is real. This church is and can be a haven for people in their spiritual recovery. But a UU church fails when it shrinks in narrow service to this one kind of theological bird and this one bird alone. UU church fails when it does not dare to be a habitat which is attractive to multiple theological birds, with all their different cultures and different songs.

Let the birdsong among us be a chorus, a plentifulness and playfulness of different musics.

Take out your imaginary binoculars and look around you, look, look.

All the fine feathered friends.

Let there be theological woodpeckers and blue jays and house sparrows and mourning doves and dark-eyed juncos and carolina chickadees and more.

Let the glory of our Unitarian Universalist religion be!

Leave a comment