In their book The Spirituality of Imperfection, Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketcham share a story about a time when a group of addiction experts from Russia visited the United States and attended several Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, “hoping to find in those smoky rooms something that could be used to fight the serious alcohol problem in their homeland.”

These addiction experts from Russia: They listened to the stories, they talked to the A.A. members, and they decided that, yes, there was something here that could help. But what was it, exactly? They couldn’t quite figure it out.

At the end of one meeting they approached their hosts, several of whom were themselves recovering alcoholics. “We want to make alcoholics like that,” they said. “Teach us how.”

The hosts smiled in gentle understanding. “Well, that’s what we’ve been doing this evening,” came the answer. “You see, you learn how to be like THAT only by BEING like that.”

“But,” the Russians sputtered, “surely there must be something you could share with us, a technique, a certain kind of approach, some kind of trick that would make this all a little easier?”

“No,” came the reply. “What you see in this smoky room, what you want to take home with you, is spirituality; and if there is one thing that all alcoholics discover, it is that there are no shortcuts to spirituality, no techniques that can command it, and especially no ‘tricks.’ That’s what we tried to find in the bottle, in booze, in alcohol. It didn’t work. What we have learned is that the only ‘technique’ is what we call ‘a four-letter word’: it is spelled ‘T-I-M-E.’”

The the story from Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketcham and their book, The Spirituality of Imperfection.

And right now, I want you to imagine something: that this worship space has been suddenly transformed into one of those A.A. meeting rooms (although these days, the rule is no smoking indoors). Imagine: you’re sitting in a metal chair. You’ve got a coffee cup in your hand.

Here we are. Some of you already have experience with this, and you’re going to feel right at home. Others of us don’t. In fact, some of us here today may honestly not be struggling with addiction, and we are also not enablers of folks who do have addictions–so if this is you, you might be wondering if today’s sermon is going to miss the mark for you. But maybe by the T-I-M-E our “meeting” is done, you’ll see that there’s wisdom here for you too, whoever you are, in this room where others are indeed working the Twelve Steps in their lives and sharing the Steps with each other.

How many of you are familiar with the Twelve Steps? It’s a set of guiding principles first published in 1939, in the Big Book, more formally known as Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How More Than One Hundred Men Have Recovered from Alcoholism. Since then, the guiding principles have been adapted to become the foundation for all sorts of recovery programs: Adult Children of Alcoholics, Codependents Anonymous, Crystal Meth Anonymous, Workaholics Anonymous, Online Gamers Anonymous, and on and on.

The American Medical Association summarizes the Twelve Steps as follows:

admitting that one cannot control one’s addiction or compulsion; recognizing a higher power that can give strength (the God of one’s personal understanding); examining past errors with the help of a sponsor (or experienced member); making amends for these errors; learning to live a new life with a new code of behavior; helping others who suffer from the same addictions or compulsions.

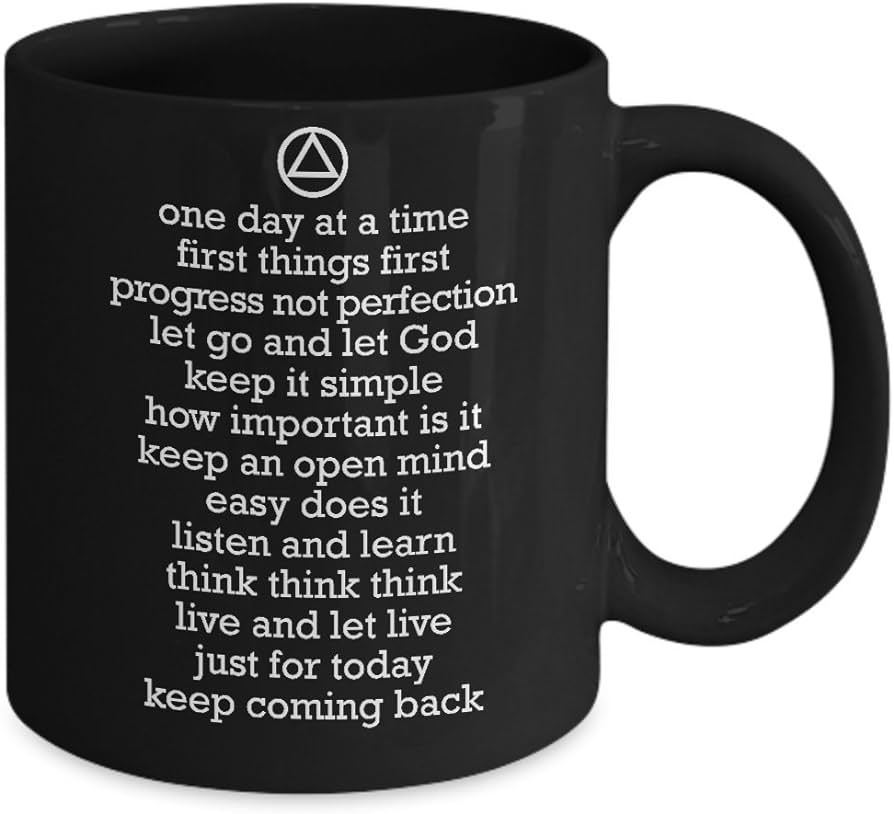

There is a powerful form of spirituality here—that’s what gathers us together in this room, in the T-I-M-E of this morning. That, and lots of humor, lots of sayings and slogans. As in:

“How come if alcohol kills millions of brain cells, it never killed the ones that made me want to drink?”

“I’m an egomaniac with an inferiority complex.”

“The good news is you get your emotions back. The bad news is you get your emotions back”

“I would rather go through life sober, believing I am an alcoholic, than go through life drunk, trying to convince myself that I am not”

“Alcohol gave me wings and then slowly took away my sky”

“Resentments are like stray cats: if you don’t feed them, they’ll go away”

“I can’t do God’s will my way”

“The power behind me is greater than the problem in front of me.”

“I used to be a hopeless dope fiend, now I’m a dopeless hope fiend.”

“The shortest sentence in the Big Book is, “It works.”

One of the main things that happens in the space of a Twelve Step meeting is storytelling.

Rabbi Rami Shapiro speaks to this in his book, Recovery, where he says, “I am not drawn to Twelve Step meetings to listen to people who are perfect; I am drawn to listen to people who are broken and who have found the wisdom in that brokenness that allows them to live in a place of love. […] We don’t ignore the trauma of the past, and our story is still rooted in it, but it is no longer controlled by it. We don’t end up where we began. […] By learning to tell our story over and over, we learn to free ourselves from the emotions attached to it. We begin to tell the story in a detached manner. We own the story; the story no longer owns us.”

Here we are, all in this room together, seated in uncomfortable metal chairs, coffee cup in hand. And now I’m going to tell my story, at least a part of it. TRUE story.

Hi, my name is Anthony. [Hi, Anthony]

I remember my Mom drugging as I was growing up—Dad ended up drugging too, but only after I left home for college, as far as I know. Before that, Dad was just Mom’s supplier—and since he was a medical doctor, the supply was endless.

I remember my Mom as either crazy high and rushing around the house, obsessively vacuuming the rugs, compulsively polishing windows and dusting and straightening; either this, or she’d be crashed on the couch, catatonic, dead to everything.

Either way, she was not available, and I felt the lack of connection in my body as an insecurity that ate into my child’s heart and made it hard to look into the eyes of my teachers; I felt it as an irritability that would not go away, a restlessness that made it hard to receive things like friendship and fun and peace and just spoiled everything and could only be soothed by busy-ness, activity, movement.

Also by snooping. I was an incurable snoop. What’s in this drawer? What’s in that desk? I marveled at how perfectly everything would be stacked and sorted. It got to be a game, although I learned, only too late, and much to my surprise, that Mom was playing the game too. One afternoon I snuck into the piano room. The rug had been carefully vacuumed in such a way that the tracings of the vacuum left cross-hatching marks. Didn’t pay much attention to that. Passed by the piano (yet another thing I was not allowed to touch) and longingly caressed the polished keys with a finger. Went straight to the cabinet and opened it, looked inside at my Dad’s classical LPs. One at a time, I slipped out Tchaikovsky, I slipped out Shostakovich, I slipped out the Red Army Choir. I looked at the albums, I wondered about the music. I knew it was my heritage, since my family had come from that part of the world. But I didn’t linger too long, since my Spidey sense started to tingle. Mom was busy downstairs, but not for long. I slipped the LPs back, slunk out of the room, smiled to myself at my cleverness.

Until later, when Dad came home from work. “Bob, would you PLEASE tell your son not to go into the piano room? I work like a slave all day and I don’t need him going in there messing things up!” Mom found out because my small footprints had ruined the perfect symmetry of the rug’s crosshatching. I hadn’t thought of that.

Mom couldn’t bear my energy. I needed to sit down and shut up. I needed to be still. Being active in the house meant making a mess, and Mom hated messes. She was at war with messes. Mom couldn’t stand a house that wasn’t as sorted and clean as a museum. If I didn’t calm down, she’d put me outside and lock the door, that’s what she’d do. I’d be out there for hours. Even when I had to go to the bathroom, she’d refuse to open the door.

One day, I tried a different strategy. Mom was drugging, so why not me? From previous times when I’d been sick with a cold, I’d noticed that the codeine-laced cough medicine Dad gave me made me feel REALLY good. Took me to a place where my body didn’t need to soothe itself through restlessness or snooping. Body felt groovy. Had no problem sitting down and shutting up then. In fact, all felt perfectly right with my world. This stuff was a straight shot to sweetness. I’d think of Mom, I’d think of Dad, and I’d tear up with the gooey feelings of love that I felt. Shortcut to love. The anger—the rage—was pushed aside, and it was a relief. Raging against the people who were your sole source of protection did not feel safe.

So my strategy was sneaking into the laundry room (where the medicines were stored) and stealing a few nips of that codeine-laced cough medicine. Did this early in the afternoon, so I’d have a couple hours to enjoy the kaleidoscope of the day.

Made me into a different kid. One way is this. I used to have this coin bank that looked like a barrel with a bunch of monkeys coming out of it. Smiling monkeys—and on the barrel, these words: “Quit monkeyin’ around and save money.” And I did. Ruthlessly. I was a greedy kid with my money. Didn’t like to spend it; wanted to keep it all because the fuller the bank was, the more I liked the sound when I shook it. Especially in my brother Rob’s presence, making him green with envy. Yeah! Rob was always wanting to borrow money, and I was always pitiless. Never gonna go there.

Until I started drugging. That’s what turned this 1% into a 99%er. Rob, you want some money? Sure! Want some more? Charge you interest? Are you kidding? What’s the matter with me? Nothing! I feel fiiiiine.

Dad eventually found out. Maybe Rob got seriously weirded out at my about-face generosity and complained to Dad. I don’t know. All I know is that when Dad found out, he bent me over his knee, spanked me good. Ordered me never to drink the stuff again. I limped away from the scene wondering why he never drew the line with Mom.

And I never did drink the stuff again. Ironically, I would end up developing a deadly allergy to the codeine that was the active substance in that cough syrup. And while my path since the days of my childhood has not led me into further drugging, it has taken me into being a perfectionist, a workaholic, a caretaker. Not that wanting to excel is intrinsically bad, or working hard, or wanting to be a caring person. But since drugs as a way of playing God in my life were out of the question, I took to codependency instead. That’s what worked in my family; that’s what worked to ease the restlessness and irritability and lack of peace that I never stopped feeling. My way of playing God, my way of lying to myself that through carefully honed technique I can command the love that I so craved and still crave. My technique. My insanity.

And that’s my story.

If this were a real Twelve Step meeting, this would be the time for me to sit down. As another Twelve Step slogan says, to people who are sharing their story, “Be interesting, be brief, be seated.” But seeing that I’m the preacher today, let me tell you another story:

It comes from the tradition of Buddhism. One day, a woman approached the Buddha in tears. She presented him with her dead child and said, “Lord Buddha, I have heard that you can bring the dead back to life. This is my beloved son who died only this morning. I beg you, Lord Buddha, restore him to me.”

The Buddha agreed, provided that the woman bring him a single mustard seed from a home in the village that had not experienced death. The woman ran to the village and went door to door to find even one household that had not been touched by death. But every single one had been touched by death. There would be no mustard seed to bring back to the Buddha. Finally, when she returned to him, her grief was no less but her attitude towards it had changed. She knew the inevitability of suffering and the futility of seeking to make things other than they are. She could now mourn her child and move on.

I share this story because it gets to the heart of the matter. Everybody hurts. Life can hurt us terribly, if not disappoint us deeply. If it’s not a dysfunctional family with a drugging Mom and dealing Dad, it’s something else. Your child dies. You are estranged from family. You carry the burden of some chronic illness. You carry the burden of having an identity that the world marginalizes. You carry the burden of our dysfunctional American politics. You feel the burden and the pain of more violence in the Middle East. Whatever it is—it’s always something. And this so very easily takes us to the reflex response that is at the bottom of every kind of addiction: to refuse to move on, to refuse accepting reality—and this refusal energy morphs into paranoia that reality is out to get you!

The essence of every kind of addiction is making war on reality, so that one can live in a world that is perfectly ordered to one’s design, reflected in exactly the way my Mom used to vacuum the piano room rug and keep the house museum clean and never stop battling against messes. The essence of every kind of addiction is the motivation behind the grieving mom who sought out the Buddha so that he could bring the child back to life again. Or trying to be the Buddha yourself, to work a miracle. Playing God. God miracle of codeine-laced cough syrup—silver bullet solution shortcut to love. God miracle of perfectionism and workaholism and every other kind of –ism you can think of, in order to force into being states of heart and mind like self-confidence, contentment, peace.

“We sought,” says Rabbi Rami Shapiro, “to create for ourselves a world of light alone, and when that failed, we sought to shield ourselves from the dark through acts of self-medication.” But Twelve Step spirituality says that there’s hope. There’s T-I-M-E. “I used to be a hopeless dope fiend, now I’m a dopeless hope fiend.” “The power behind me is greater than the problem in front of me.”

One of the ways I practice Twelve Step spirituality is through a prayer of my own. I created it in the context of yet another circumstance in which I felt the itch to play God in my life. Being judge, jury, and executioner all rolled up into one. It was years ago. I was sitting on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, watching the fascinating world go by with all its exotic and exciting sights and scenes, but feeling like I was on the outside, looking in. Not able to take it all in, not able to be in the moment and feel joy. Feeling wretched and alone, “other,” left out, ill-prepared for life because I’d grown up in a screwed up family. Feeding the stray cats of my resentments, and the more I fed them, the more resentments gathered…

Out of this turmoil came the words of a prayer that I continue to pray to this very day, some days more than others…. Something like this:

I forgive all the ways in which my life appears to fall short.

I trust that whatever I truly need will find its way into my life.

I am grateful for what I have.

My holy trinity: forgiveness, trust, gratitude.

It was my way of doing what the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous says: “ceasing from fighting anything and everyone.” Stopping the war and letting go, letting go of all my pride that says I am entitled to whatever I want. Letting go of pride, letting go of greed for MORE, letting go of the itch to order my world as my Mom tried to order her house–and relaxing. Relaxing into the sea of my life. THIS is the only power I really do have: not hard power to command the world to be as I want it to be, not hard power to command love, but soft power to let go and relax, soft power to let the sea hold and carry me along its currents.

Let go and let God.

This is not about passivity. This is about learning how to act from a different head and heart space. This is learning about how you can help to bring love to birth in the world–your private world and the public world–without the resentment and aggression and perfectionism. How you can step up, show up, do your part, then let go.

Forgiveness, trust, gratitude. Trusting that if I take one step at a time, with every step life is going to meet me with what I need. The daily bread will come. “Alcoholism is a disease of faith,” says the writers of The Spirituality of Imperfection. “Alcoholics often develop a cynical attitude toward life, not seeing anything to believe in. When you persistently feel the need to change your consciousness through drugs or booze, you are expressing a lack of trust in yourself, in your ability to tolerate life undiluted, to find value in your own, unadulterated experience.” That’s what I saw Mom and Dad doing all the time. I did it too. I knew and know this kind of self-mistrust intimately.

But there is another way. It’s like my man Ralph Waldo Emerson says, in one of my all-time favorite quotes: “There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till.”

Forgiveness, trust, gratitude. The power behind me which is greater than the problem in front of me. The Higher Power I have to turn my will and life over to again and again, lest resentment be the poison I keep on drinking in the insane hope that it’s gonna kill the other people who hurt me. Praying my prayer again and again, to open up my heart. It’s just like washing the dishes. Never happens just once. It’s just part of the human condition to slip into the mania of wanting to play God. But as Bill Wilson, creator of the Twelve Step program, says, “First of all, we had to quit playing God.” “I can’t do God’s will my way” “Let go and let God.”

The shortest sentence in the Big Book is, “It works.”

Leave a comment