September 6, 2023: The New York Times headline screams across the page: An aging America needs an honest conversation about growing old. “In less than two decades,” says the newspaper in a voice I imagine to be like that of the narrator of a disaster movie, “the graying of America will be inescapable: Older adults are projected to outnumber kids for the first time in U.S. history. […] America may still think of itself as a young nation, but as a society, it is growing old. Thanks to falling birthrates, longer life expectancy and the graying of the baby boomer cohort, our society is being transformed.”

Because West Shore member Anne Osborne purchased this sermon at the last annual service auction, we are going to have this honest conversation among us right now. (We love you, Anne!) And, to this honest conversation, I will be bringing all sorts of wisdom–as is our practice as Unitarian Universalists–including science, including religion, and also including fairy tales.

Fairy tales? The fairy tale, says psychiatrist Allan Chinen, is a treasure trove of human psychological and spiritual wisdom. Unlike many artistic creations which are produced by single individuals at single points in time, genuine fairy tales transcend individuals. Genuine fairy tales are handed down over the generations, with the Darwinian implication: that they survive over time exactly because they are so valuable, exactly because they preserve priceless human wisdom we do well in any age to heed.

In the vast majority of fairy tales, says Dr. Chinen, the protagonists are children or youth, and so, interpretations of these tales emphasize the psychology of childhood and youth and the tasks of growing up. However, there happen to be a small number of tales in which the protagonists are “old”–meaning middle-aged and beyond. These are called the “elder tales,” and these deal with the unique issues and tasks of psychological and spiritual growth in old age.

Today, the elder tale entitled “Fortune and the Woodcutter” (which Scott performed a moment ago), will provide the basic wisdom structure of our honest conversation about America’s aging.

This elder tale begins with poverty. After his two sons leave home to seek their own fortunes, and after more years of labor in the woods, one day the woodcutter makes a painful discovery: that he has little to show for all his years of work. He is poor. Dr. Chinen counsels us to interpret this as an honest insight about the infirmities of aging and all the losses that take place. There are just so many. If you are older, think of a store you knew that is no more. Think of a building you knew that is no more. Think of people you love who are no more. Think of the smoothness of your skin or the strength of your body, which are no more.

Humorist Roger Rosenblatt touches on some of this when he says, “One thing I need to remember is which day for which doctor. On one day last week, I had a vascular sonogram in the morning, consulted my ophthalmologist in the afternoon, made an appointment with a retina specialist, spoke to my primary care physician about test results and put off my dentist. As a result of such activities, my vocabulary has increased. I now can say ‘occlusion’ — and mean it. Has anyone seen my oximeter?”

Ha ha.

Roger Rosenblatt goes on to mention “another of aging’s unnerving surprises. You disappear from the culture, or rather, it disappears from you. Young women and men shown on TV as world famous, you’ve never heard of. New idioms leave you baffled. You are Rip Van Winkle without having fallen asleep.” Can you relate?

With less humor and more sobriety, the Rev. Carol Johannsen wonders, “I am … an elder, age 71 and counting. And I wonder: what about when I retire? What happens as I lose physical strength? Have I already experienced the best of life? I resonate with the words Peggy Lee sang in the 1960s, ‘Is that all there is?’ I hope not.”

Today’s elder tale opens with an honest acknowledgement of poverty, but we are not done mining this symbol for all it’s worth. Because, the personal losses symbolized by the fairy tale’s poverty are interwoven with negative stereotypes about aging, together with a pernicious dynamic social scientists call “stereotype threat.”

The negative stereotypes are of time immemorial. Mimnermus, a Greek from the 7th century B.C. (that’s 2600+ years ago) wrote, “The fruit of youth rots early; it barely lasts as long as the light of day. And once it is over, life is worse than death.”

Fear of old age is ancient, and it is universal. Maggie Kuhn, founder of the Gray Panthers movement, writes, “There are six myths about old age: 1. That it’s a disease, a disaster. 2. That we are mindless. 3. That we are sexless. 4. That we are useless. 5. That we are powerless. 6. That we are all alike.”

Some scholars theorize that today’s particular idealization of youth is energized by the twin ideals of capitalism and materialistic science. Capitalism says that people are valuable insofar as they are working, making money, and buying things. Materialistic science comes into play when people’s minds and bodies start to wear out and need so-called fixing, with the result that they can get right back to living out the capitalist dream. Capitalism is essentially a heroic paradigm, which puts people upon an endless quest for power, strength, beauty, and wealth; materialistic science wants to serve up life extension interventions and technology that could make any and all of us “forever young.”

Whatever the source of the negative stereotypes about aging, they are there, and they are pervasive. Every time I hear someone say that President Biden is too old, I catch the sour smell of nasty ageism. Whenever was the accumulated wisdom of decades and decades of proven service in some of the highest offices of the land irrelevant to our time of multiple wars, a dysfunctional House of Representatives, and the most serious threat to our democratic way of life in history?

Negative stereotypes about aging:

The most important thing to know about all of these negative stereotypes is that they are contagious. They help to create the poverty. David Robson, author of the powerful book The Expectation Effect, says a little about what drove him to write it: “The expectation effect concerns how our beliefs become self-fulfilling prophecies through changes to our behavior and our physiology. [T]he research on aging … demonstrates this beautifully. [The research has] shown that people who have a negative belief about aging – who associate aging with a kind of inevitable decline with disability and with a lack of independence – that they actually age much more quickly. Their actual biological aging is accelerated. [T]his can be seen right down to the cellular level. So the length of the protective caps at the ends of the chromosomes for example, these telomeres, they tend to be much shorter as people get older and they’re much much shorter amongst the people with the negative beliefs compared to those with the positive beliefs. […] So people who hold the negative beliefs about aging live for seven and a half years less than people with the positive beliefs. So that instantly … got me interested in just how that could be….”

This concept of the “expectation effect” is one of the most important things anyone can know about themselves. For each and every one of us, there is an excess of life possibilities, but often, only few of them are ever realized. It’s because our brains are “prediction machines” which allocate the use of personal resources in line with the expectations we have for ourselves (or the expectations others have for us.) Any individual’s potentialities are through the roof, but which of these potentials are actualized–and to what degree–can be tragically minimal.

We must all understand that whenever we personally propagate negative stereotypes about aging–or whenever allow another person’s joke or comment to stand (as in “President Biden is SO OLD” ha ha ha!!!!)–we are helping to create impoverishment. When we joke about aging or when we talk about aging in such a way as to reinforce stereotypes that aging means

Being fragile

Being lonely

Being forgetful

Being grumpy

Being sick

Being boring

Being useless

Being a burden

… when we talk like that or joke like that, we are helping to create impoverishment. The scientifically-verifiable dynamic is called “stereotype threat.”

If we are to be a people of anti-oppression, it needs to stop.

The New York Times wanted an honest conversation about aging, and I wish it were more honest about how all the negative stereotypes are a huge part of the problem. In fact, in my reading, the language of the article only reinforces negative stereotypes. “The graying of America will be inescapable: Older adults are projected to outnumber kids for the first time in U.S. history[!!!!]” Like it’s a horror story or something.

Thank the Buddha for fairy tales. Because our honest conversation is only getting started.

Because look at what that plucky woodcutter did, in the face of all the poverty: He “vows to work no more.” “He decides to stay in bed” and he waits for Fortune to find him. His wife repeatedly tries to change this, but he resists her at every turn. “It is astonishing,” says Dr. Chinen. In tales of youth, the young hero or heroine must leave home and aggressively seek out Fortune. By complete contrast, the old woodcutter stays home, hunkers down in bed, and drops out of society.

Alternatively, he could have continued trying to become a success as society defines it: running and running on the “forever young” treadmill in quest of capitalistic values. Or, he could have succumbed to the influence of negative stereotypes about aging and essentially die psychologically and spiritually–long before the death of his physical body.

But no. He is resolved to live live LIVE up until the point that his physical death makes that impossible. To live abundantly up till the very moment his body ceases to function. Maybe he doesn’t know how at first. All he knows is that he’s got to follow his intuition, stated well by the Rev. Carole Johannsen, who says, “A human being would certainly not grow to be 70 or 80 years old if this longevity had no meaning for the species to which he belongs. The afternoon of human life must also have a significance of its own and cannot be merely a pitiful appendage to life’s morning.” The woodcutter intuits this. He intuits that old age is (as Joan Chittester puts it) “a time to come alive in ways one has never been alive before.” “The last phase of life is not non-life; it is a new stage of life.”

The old woodcutter steps off the treadmill of a youth-worshiping society, and in this way, he opens up room for a countercultural vision of elderhood to emerge. He opens himself up for a new vision of what it means to be “young old” (65-74), or “old old” (75-84), or the oldest old (85 and beyond).

Do you happen to be in one of these age ranges?

If you are, good! If you aren’t, you are still in the right place, because (as we’ve just seen from our exploration of the expectation effect and “stereotype threat”) everyone, no matter what their age happens to be, is an integral player in ensuring that the cultural environment is clear of noxious stereotypes. You do it because you love other people. And, you do it because you love yourself, because you will yourself be the victim of any ageism you espouse, soon enough….

What this time of “working no more” and “staying in bed” might look like can vary. I suspect that it involves a lot of personal reflection and exploration. Mandatory would be honesty about the degree to which you have bought into negative stereotypes about aging. That’s mandatory.

But there’s more, much more to this. The Rev. Carole Johannsen suggests what this might be when she acknowledges the work of developmental psychologist Erik H. Erikson, “whose eight Stages of Life, set out in his 1950 book, Childhood and Society, laid the foundation for modern studies [of aging]. Erikson’s stages,” she says, “cover a lifespan, with each stage defined by the use of contrasting words that indicate either a successful passage through the stage or an incomplete one. For the eighth stage, Maturity, the contrast is “Integrity vs. Despair.” In this stage, a person either accepts her life, with all its mistakes and blessings (Integrity), or finds the past not only unacceptable but realizes that death is on the horizon and there is no time for do-overs (Despair).” Rev. Johannson now gets to the main point: “The move toward Integrity is spiritual work. Looking back, taking stock, giving thanks, knowing shame, reconciling where possible and forgiving when necessary, oneself as well as others, and accepting … forgiveness – all this is the [spiritual work necessary in the second half of life.]”

And THEN the Rev. Johahnsen says: “Yet most elders are left to do this alone.” She says, “In my experience, faith communities give little attention to the spiritual needs of elders. They may host luncheons, provide rides or visit shut-ins, all of which are needed and usually appreciated. It is no small thing to continue to [go to church and be a part of a church community]. But,” she says, “I believe more is needed. Just as children and teens need age-appropriate spiritual support, so do elders.”

If you are “young old” or “old old” or the “oldest old” (85 and beyond), has that been your experience at West Shore? I want to hear from you. The only critique of the woodcutter fairy tale I have is that it suggests that we as individuals can step off the social treadmill, drop out, and create for ourselves a new vision of positive elderhood. I don’t think so. It’s a collective achievement. It’s something we need to do together.

Can we do better at this, here at West Shore? Shoot me an email. Talk to me. What do you think?

But now–back to the fairy tale. The Stranger comes. Remember the Stranger? He’s a magician. He uses the old woodcutter’s mules to find treasure. Happily, the soldiers come and the magician scrams, leaving behind the treasure. The mules then return home, with the treasure, and so the story ends: “’Fortune did come to us after all!’ the old wood cutter exulted. And when the old man and his wife gave half their treasure to their sons, and half the remainder to the poor, they were still as rich as rich could be!”

Magic comes to the woodcutter and his wife, in the midst of all the poverty. That’s the amazing lesson of the tale. That magic is not just for children and youth, but for elders as well. But it is a different sort of magic. Magic in youth tales comes effortlessly. “The young man or woman,” says Dr. Chinen, “is freely given help by a fairy godmother, or some magical treasure, and such generosity reflects the naive optimism and wishful hopes of youth.” The magic of this elder tale, however, can unfold only on the foundation of the old woodcutter’s many years of hard labor and hard-earned skill. This is symbolized by the role of the mules in the story. The role of the mules is key. “For all his powers, the Stranger apparently cannot obtain the treasure without the beasts.” “The mules return home by themselves only because they have followed the same trail many times before.”

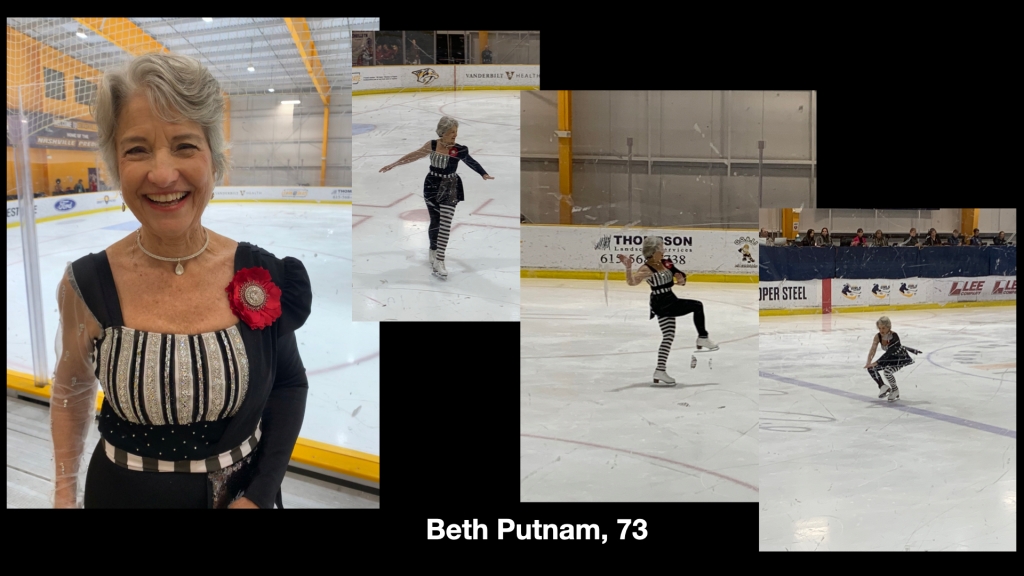

Last week I was in Nashville, at the 2023 International Adult Figure Skating Competition, with competitors from Australia, Canada, Germany, Spain, the U.S., and on and on. Rachel and I were supposed to compete but my aging body said no. I’ll need both my hips replaced before I can get back out there. Rachel was able to skate and did wonderfully. I was stuck in the stands watching all the skaters from around the world who are 30 years and older. Here was someone who caught my eye:

She is Beth Putnam, 73. I don’t know her from Adam. But there was something special about her energy and smile. When she came up to the stands, I limped to her and asked to take her picture. I hurriedly said I was a Unitarian Universalist minister and was preaching about aging the following Sunday and asked if I could take her picture and she said yes.

She is someone who defies age stereotypes! I see this sort of thing all the time in adult skating. People whose skating will never appear on TV because, quite frankly, their skating skills (developed as adults) are a million miles away from the young people we do see on TV. But they skate anyhow and there is a glory to it that no nineteen-year-old or twenty-three year old Olympian competitor can ever, ever approach.

Above all, I’m wondering about Beth Putnam’s mules–in other words, her character attributes which only a lifetime of living could forge, which served to bring the magic of skating in later life to her. I’m wondering about the wisdom she’s lived into over the years, about success and failure. I’m wondering about the role shame has played in her life, and how she learned to free herself from shame’s terrible bind. These are all examples of hard-earned knowledge and virtue which, on the surface, have nothing to do with skating; but on this foundation of all that’s gone before, in her eldership years, she has been enabled to build a new, magical chapter in her life. Her magical figure skating at 73 years old!

Magic is just not for children and youth. Magic can come in old age also. It’s very different, but it can come.

Aging is NOT just a downhill slide into oblivion.

Maybe your magic won’t ever be figure skating at 73 years old. So what will it be? What will the magic that is perfect for you be?

“Aging is not ‘lost youth,’ says Betty Friedan, “but a new stage of opportunity and strength.”

If you are “young old” or “old old” or the “oldest old,” I guarantee you, you’ve got well-trained mules who know the way home. If you happen to be in a negativity spiral about aging, it’s time for you to unplug from the fantasy of perpetual youth and do as the old woodcutter did. Just get in the bed, let fortune find you. Be a part of this spiritual community that wants your spirit to grow as much as it wants children and youth and younger adults to grow. Do your spiritual work around aging: call out the negative stereotypes, reflect on your life’s ups and downs, face your regrets, forgive others and forgive yourself, mourn your losses, reconcile yourself with your changing body, open yourself up to your growing spirituality, find a way to give back, find a way to mentor those who need your wisdom.

Be the elder you were meant to be.

Don’t die psychologically and spiritually before the death of your body.

Live live LIVE and never stop living and only when your physical body is done living, only then, die.

The magic is real.

Allow that magic to find you.

**

**

“Fortune and the Woodcutter,” from In the Ever After: Fairy Tales and the Second Half of Life, by Allan B. Chinen.

Once upon a time, there lived an old woodcutter with his wife. He labored each day in the forest, from dawn to dusk, cutting wood to sell in the village. But no matter how hard he struggled, he could not succeed in life, and what he earned in the day, he and his family ate up at night. Two sons soon brightened his hearth, and they worked by his side. Father and sons cut three times the wood, and earned three times the money, but they ate three times the food, too, and so the woodcutter was no better off than before. Then the young men left home to seek their own fortunes.

After twenty years, the old man finally had enough. “I’ve worked for Fortune all my life,” he exclaimed to his wife, “and she has given us little enough for it. From now on,” the old man swore, “if Fortune wants to give us anything, she will have to come looking for me.” And the woodcutter vowed to work no more.

“Good heavens,” his wife cried out, “if you don’t work, we won’t eat! And what are you saying? Fortune visits great sultans, not poor folk like us!” But no matter how much she tried to persuade him–and she reasoned, cried, and yelled–the old woodcutter refused to work. In fact, he decided to stay in bed.

Later that day, a stranger came knocking at the door, and asked if he could borrow the old man’s mules for a few hours. The stranger explained that he had some work to do in the forest, and that he noticed the woodcutter was not using the mules. The old man agreed, still lounging in bed. He simply asked the stranger to feed and water the two animals.

The stranger then took the mules deep into the forest. He was no ordinary man, but a magician, and through his arts, he had learned where a great treasure lay. So he went to the spot and dug up heaps of gold and jewels, loading the booty on the two mules. But just as he prepared to leave, gloating over his new wealth, soldiers came marching down the road. The stranger became frightened. He knew that if the soldiers found him with the treasure, they would ask questions. His sorcery would be discovered and he would be condemned to death. So the stranger fled into the forest and was never seen or heard from again.

The soldiers went along their way, noticing nothing unusual, and so the two mules waited undisturbed in the forest. After many hours, they started for home on their own, following the trails they had used with the woodcutter for many years.

When they arrived at the woodcutter’s home, his wife saw the poor animals. She ran upstairs. “Dear husband,” she cried out, “come quickly. You must unload the mules before they collapse!”

The husband yawned and turned over in bed. “If I’ve told you once, I’ve told you a thousand times. I’m not working anymore.”

The poor woman hurried downstairs, thought for a second, and then fetched a kitchen knife. She ran to the mules and slashed the bags on their backs to lighten the load. Gold and jewels poured out, flashing in the sun.

‘Gold! Jewels!” she exclaimed. Instantly, her husband was downstairs, and he stared in astonishment at the treasure spilling into their yard. Then he grabbed his wife and they danced deliriously. “Fortune did come to us after all!’ he exulted.

And when the old man and his wife gave half their treasure to their sons, and half the remainder to the poor, they were still as rich as rich could be!

Leave a comment