Every year in January, we celebrate one of history’s greatest leaders, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and his dream of racial and social justice.

But he had to grow into his leadership. And his relationships were critical to this.

Of course this is true. But in our American culture of radical individuality, we can fall for the illusion that heroes like Dr. King were purely self-made.

Even more than that–that they sprang from the womb fully formed in all their abilities.

There’s probably other reasons why regular people like you and me might shy away from calling ourselves leaders, but this is a big one. Because we tend to make great leaders into superhuman saints who don’t need to learn, who don’t make mistakes, who don’t need encouragement from other people.

In this respect, one facet of a spirituality of socal justice is about bringing leadership down to earth–bringing compassion and patience and understanding to the real process of learning how to be the change you wish to see in the world.

So let me tell you a not-very-well-known story about Dr. King’s leadership formation process. It had to do with the time he was invited to become part of the Montgomery bus boycott. As you know, first there was Rosa Parks—her refusal to obey the bus driver’s demand that she give up her seat. Dr. King’s biographer Marshall Frady tells us what happened next: “[Rosa Parks’ NO, and her arrest,] quickly set off a spontaneous combustion among Montgomery’s black citizenry to boycott the city’s segregated bus system. Almost immediately, mimeographed leaflets calling for the boycott were coursing through the city’s black neighborhoods. But when, the night of Mrs. Parks’ arrest, a local social activist by the name of E. D. Nixon phoned the young Martin Luther King Jr. to ask him to join in the boycott movement, King, out of some uneasiness beyond just his absorption in his multiple other duties, seemed curiously reluctant: ‘Brother Nixon, let me think on it awhile, and call me back.’” Marshall Frady goes on to say that Nixon became concerned about King’s hesitation, and so he went on to call King’s friend Ralph Abernathy. Abernathy turned right around and called King, telling him that his cooperation in the boycott effort would be of monumental importance.

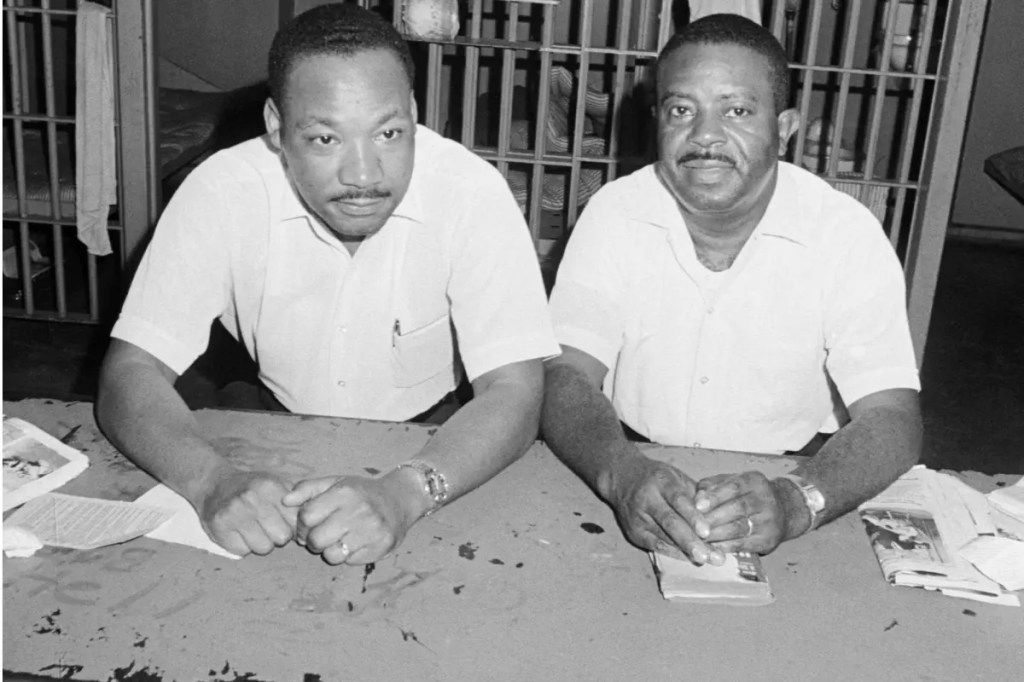

Ultimately, it was Abernathy’s counsel which led to Dr. King saying YES.

And from that YES, everything flowed. The respect he earned as leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott led to his role in founding (with others) the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and this led to his leadership in civil rights campaigns in Albany, then Birmingham, then Augustine and Selma, and then the March on Washington and his soaring “I have a dream” speech, and beyond.

But it all started with Montgomery and the not-very-well-known story of Dr. King’s initial hesitation which gave way to Ralph Abernathy’s encouragement.

What if Dr. King had, instead, stayed in the position of “thinking on it awhile”—which is really just a nice way of saying NO? What if? Without Montgomery, would there ever have been an “I have a dream”? Hindsight is 20-20. “We live forwards,” said philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, “but we understand backwards.” With only the knowledge that is given us in the moment—already full of the pressures of existing responsibilities and anticipations of future work we already know of—it is truly understandable and fully human to hesitate when a call to something new comes before you.

Dr. King was only human, and this is something we need to be reminded of, so that we can be confident leaders in our own right.

Especially because there’s confusion out there, about what it takes to learn how to be an activist. “One person acting alone” is the message we hear over and over again. Nothing or not much about family, the larger supportive community, the worship services, the committee work, the coalition building, the flurry of letters and emails and phone calls, and, in the midst all of it, above all, key sustaining friendships. People whose judgment you trust, so that even if all the world is criticizing you, if THEY believe in you, YOU believe. People who will lift you up when you need it; people who will bring you back down to earth, when you need that.

Nothing about any of this, mentioned in the standard story. Just one person acting alone. Rugged individualism.

It’s just not true. You can’t get to Dr. King without his parents and family and teachers, the Black church community, liberal religious communities like this one, all the committee meetings, all the worship and prayer and hymn singing, all his friends and colleagues.

You just can’t get to him without Ralph Abernathy—the man who reconnected him to his sense of call and purpose when he hesitated. The man who was with him throughout, until the very end and beyond.

I’m asking you this morning: Who is your Ralph Abernathy? Who believes in you, so you can believe?

There’s many dimensions to a spirituality of social justice. Mary-Jo spoke to the heart sense dimension; Rev. Shirley spoke to the self-care dimension; and right now I’m speaking to the dimension of our relationships and how we need to help eachother into the activism that is right for us and sustainable for us.

You know, I’m excited about Tim Walz as Kamala Harris’ running mate. I really am. Hope and joy are buzzing through their politics. What a change. Thank the Buddha.

But it’s Tim Walz’ style of encouragement and support that I’m particularly happy about. He’s giving that to Kamala. He’s giving it to all of us.

And there’s nothing new about it. It’s who he is.

I was reading an article the other day about his old football team at Mankato West (in Mankato, Minnesota) back when he coached their defense. This was years ago, in the mid-to-late 1990s. The team had been terrible when he got there–it had gone 1-26 over the course of several years. But when Walz arrived, he brought a kind of Ralph Abernathy energy that transformed things.

Chuck Wiest, one of his players, said about him, “He was so full of positive energy. He was our hype man.”

Adam Friedman, another player, has this to say: “When I was a junior, I was a punt returner. I muffed a punt, and they could tell I had the yips. Coach Walz came up to me and said, ‘We’re not going to fix this today. We’re going to put somebody else in for you, but we’re going to figure this out, don’t worry.’ I was [really upset] at the time and remembered it. A year later, I returned a punt 80 yards. We ended up scoring and won, and I got interviewed after the game. Coach Walz came up to me and said, ‘What’d you say to them?’ I said, ‘I thanked my blockers.’ He said, ‘Aw, man, good work. You should take credit, too, though. That was amazing!’”

Yet a third player remembers him saying, “Let’s go! You’re better than that! This is how we’re going to do it! We’ve got to understand our past, but that’s not our future!”

“Are you dedicated? Do you want to be a football player or somebody who plays football? We’re in it! Together!” That, his players say, was the biggest thing he brought to the table. The culture of enthusiasm.”

West Shore, a spirituality of social justice can mean so many different things. But this above all:

SPIRIT

SPIRITEDNESS

Let’s encourage eachother–be Ralph Abernathys and Tim Walzs to each other.

If you’ve said NO to an invitation to get involved, must that be your final decision? What if you said YES instead? Where might that take you?

Do you want to be the change you wish to see in the world? Or just someone who waits passively at the sidelines?

Let’s go!

We’ve got to understand our past, but that’s not our future!

We’re in this, together!

Amen.

Leave a comment