The first time I ever thoughtfully considered that I had a relationship with my body was when I was 12. This is different from something more casual or superficial. Of course I knew I had a body. But the depth of that knowing changed when I realized that my body had me.

I was 12, and I was living in a dorm called Beatty Hall in Colorado Springs, Colorado. My family was 830 miles away in Texas. I was spending my 9th grade year as a part-time student who was in full-time training at a skating club called The Broadmoor which was famous for the number of national and international skating champions it had churned out over the years.

My family had hopes I could turn out to be another of these champions.

One day I was relaxing in the common area of the dorm and I was bored by the TV show nattering away in the background which had my fellow skaters riveted. It was the soap opera General Hospital, with its saga of Luke and Laura. Luke and Laura were all the rage in 1980. But, as I said, I was bored by it, so I found myself scanning the bookshelves and I found one that piqued my interest. It was a biography of St. Francis of Assisi.

I ate that book up. (Looking back, I suppose this was an early sign of my call to ministry. My future, hinted at.)

But the thing I read in the biography which is particularly relevant to my topic today is about how St. Francis came to call his body “Brother Ass.” At first I did not understand. Brother Ass? I laughed out loud and it caught the attention of one of the skaters in the common room who happened to be the Australian men’s figure skating champion from 1979, who turned away from the TV to me and asked what was so funny. I told him that St. Francis had used a cuss word to describe his body. He said, no, all that St. Francis meant was that his body was like a donkey. Ass means donkey.

Oh.

I read more and learned that St. Francis used it as a term of endearment. When he was a younger monk and more zealous, he saw his body as the source of all temptation and something to be beaten into submission. Things changed when he got older, though. His view softened and he realized that his body was his singular and unique vehicle for experiencing the world. It deserved gratitude. It also deserved compassion, since it was vastly vulnerable to every sort of pain and malady.

Gratitude and compassion. That I could understand. My body was my vehicle for figure skating and I was very much grateful for the sheer delight I felt in moments when my skating technique clicked, my body and the laws of physics became one, and I could spin like a top in the air and land effortlessly.

The sheer delight of it.

I also knew about vulnerability. I had a coach who often yelled at me, and my body absorbed that stress into its muscles. They’d end up feeling like lead. It only made me more error-prone. I fell so many times while learning the axel jump–it’s when you jump forward and rotate 1 ½ times in the air and land backwards–that I developed bursitis in my right hip, which is inflammation of a fluid-filled sac on top of the bone. I limped when I walked. The pain was sharp and intense and only got worse at night.

At around this same time, my family was dealing with another sort of pain. My Baba had terminal brain cancer. I’ll never forget the day I got the phone call from my Mom. Baba was dead.

I recovered from my bursitis, but I was also learning that there are some physical ailments you can’t recover from.

Sometimes Brother Ass gets better, and sometimes you must find a way to make peace with your life knowing that Brother Ass won’t get better.

Either way, you are in constant relationship with your body.

You have a body, and your body has you.

Some of us believe that our souls are immortal and there is an afterlife. Others believe that consciousness is only temporary and that, after death, the only thing remaining is the impact of our deeds. But either way, whether your aliveness is immortal or temporary, its here-and-now quality is impacted in countless ways by what’s happening with your body.

Above all, Brother Ass has lessons to teach. When we think of spiritual teachers, what might come to mind are enlightened beings or sacred scriptures. The Buddha and Carl Sagan. The Bible and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. But let us not forget our bodies.

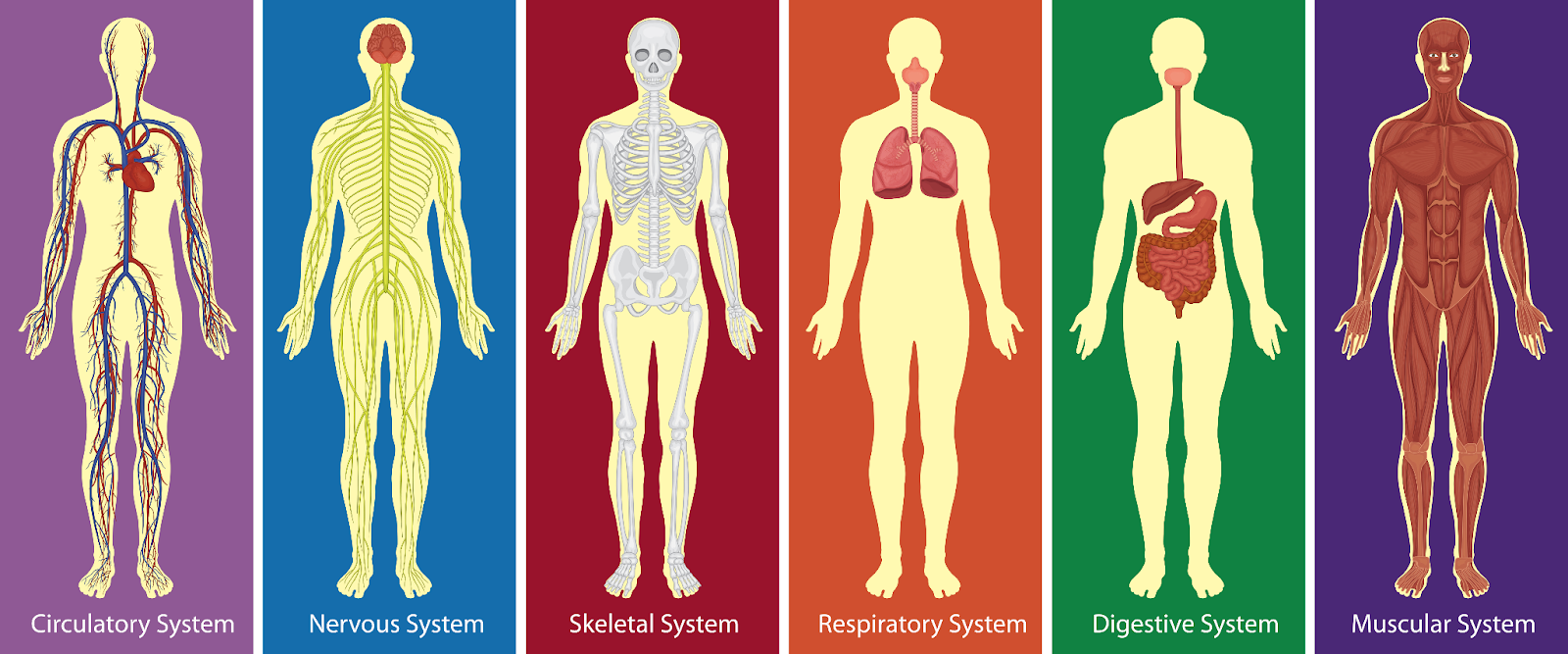

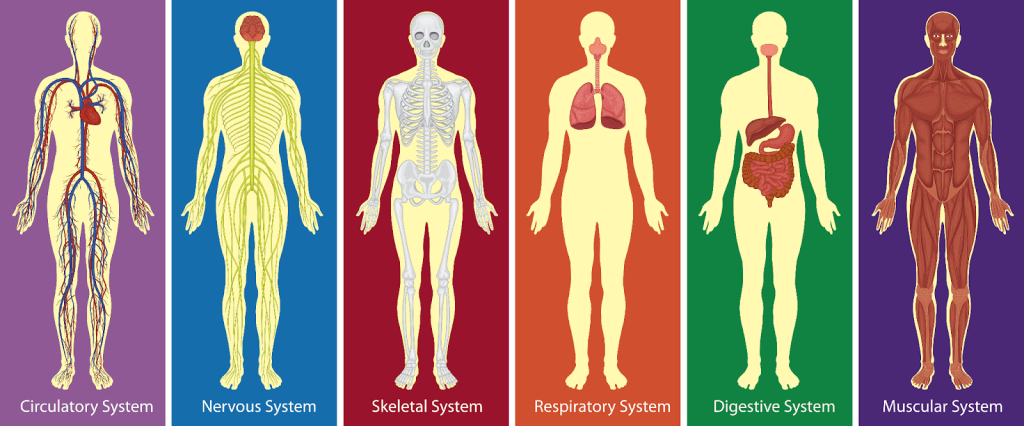

Right now, we are inviting into this sanctuary our bodies as the spiritual teachers they are–especially by virtue of their vulnerability. Imagine, in fact, the image of the body that you see before you becoming a permanent addition to the world religion panels behind me.

It is truly worthy.

Because, for one thing, the body teaches us humility. One of the signs of spiritual evolution is a clear recognition of the ever-present temptation to act like God and the even clearer decision not to do so. Whenever we feel entitled to the world bowing to our will, that’s when we’ve fallen into the temptation. Whenever we insist that things must dance precisely to our tune and proceed exactly to our satisfaction, we’ve made ourselves into something Divine.

Imagine, atheists whose controlling attitudes and behaviors make them act just like the God they don’t even believe in!

But it’s not just atheists doing this. It’s everyone.

And then a physical injury happens. At least my hip bursitis when I was 12 was meaningfully related to trying to learn something. So often, the cause is sheer accident. You slip on the ice in winter and break an arm. Your car is rear-ended and you end up with whiplash. You drop a glass bottle of juice as you’re walking up cement stairs and you try catching it (like a ninja!) as it bounces–but glass bottles don’t bounce on cement, they shatter.

That happened to me. I’ll show you the scar if you like. A large shard severed the webbing between my right-hand thumb and forefinger and, because I was planning on seeing a movie that night, I was in denial about how bad it was. Then I almost fainted from loss of blood. My ex took me straight to the ER and six hours later, right hand sewed up and bandaged, I returned home. No movie.

I was in seminary at the time. For six weeks, this right-hander was engaged in a crash-course of learning how to write left-handed. It’s just what I had to do.

Accidents force you into awkward detours from your best laid plans. And, despite the disappointment, you’ve got to go into those detours. You’ve got to give your healing process all the time it needs, because if you don’t, pain will be your instant feedback. Now, or later.

As someone who is learning to live with Long Covid says, one must “trade resistance for rhythm.”

You’re learning patience the hard way, if you’re typically impatient. But you’re also learning you’re not God. You’re only human. Maybe it’s even accompanied by a self-deprecating sense of humor. Isn’t that what makes slapstick comedy so funny, as when an egocentric person’s chair is pulled out from underneath them, and they discover they’re not nearly as fancy as they thought they were, exactly when their butt hits the ground?

To be human is to be vulnerable.

To be vulnerable is to be human.

Therefore, we must be kind. We must learn kindness towards Brother Ass and not be unfeeling, or harsh. That’s a second kind of spiritual lesson our bodies teach us.

Consider how people hold stress in their bodies. It could be caused by a figure skating coach yelling at you, as I experienced when I was 12, or maybe someone else is yelling at you. You’re driving and someone honks a horn at you. Maybe you do it to them.

Or, say you’re scrolling social media and it’s doom and gloom. It’s one thing after another. The world is on fire and you don’t know what to do. Stress!

Then again, it could be your desk job, the pile of things to accomplish with never enough time, and you sit rigidly in your chair facing your computer screen, relentlessly working, while the tension in your neck, back, and shoulders only builds.

All kinds of stress and challenges, but one of the worst is waiting for test results. What will the blood test reveal? How about the biopsy? The CT scan? The MRI? Maybe everything will be ok. But it won’t necessarily stop you from imagining the worst.

Stress fills the body with lead-like heaviness. Squeezes your blood vessels tight. Your heart has to pump blood harder, and when this becomes chronic, it causes major problems. So it is sheer kindness to find ways to soften the tension. Maybe you won’t be able to banish it completely. But can you give yourself moments of reprieve? Moments of peace?

Take a moment with me now, seated right where you are.

- Take a big breath in, then let it all the way out.

- One more time.

- Now try shoulder rolls: Lift your shoulders up towards your ears, then roll them back and down. Repeat in the opposite direction

Yet more kindness is needed in the face of aging. If you’re older, do you remember a time when you went to the doctor just once a year? But now it’s all the time. The 75 year old comedian Andy Huggins says, “As far as social media is concerned, you can follow me on MyChart.”

Furthermore, it used to be that, if something hurt, you could get it fixed. Now, some things can’t be fixed.

Hard if that’s true for you. Hard to see that in the people you love.

From Buddhism comes a blunt acknowledgement of the human condition, entitled “The Five Remembrances,” and the very first one states: “I am of the nature to grow old. There is no way to escape growing old.” Accepting this, we must find a way to learn kindness towards our aging bodies or those of others and to learn new ways of being with them as they are.

When I’m at the rink figure skating, I’m surrounded by children and teenagers whose energy I wish I could bottle. There I am, at 58 years old–I know, I’m still a youngster to some of you! Even so, the so-called “youngster” I am has had to learn to make peace with how my gas tank is never more than ¾ full. When I am on the ice, I meet my fatigue every time. I carry Brother Ass out there with me. But I have learned, as a point of kindness to myself, that it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. I can feel fatigue and yet still get out there and skate. I can feel tired and yet trust that I have more energy reserves than I might think. I refuse to give up something that brings such pleasure to me because I’ve succumbed to the stereotype that older people can’t do stuff anymore.

I’m going to live as much as I can up till the moment I die, and I will not die before my death.

Will you join me in that?

Let me also say that whether it is physical stress we are talking about, or aging, or seasonal allergies, or any other kind of infirmity or illness, when we’re paying attention to our personal experience of that, it’s like a wake-up call. Wake-up calls are the third kind of lesson Brother Ass teaches.

At the very least, we are woken up in compassion to the struggles and pains of others. We are more likely to be patient and kind with them.

It doesn’t matter whether your own physical infirmities match up exactly with those of others. My hip replacement surgeries have woken me up to the knee replacement surgery that member Pam Smith is facing, or the broken leg that Dawn Bellinger is healing from. And on and on. We are woken up to this different side of being in community with each other.

I went to visit Dawn the other day, actually, and we both discussed yet another way physical infirmity can wake you up. You are woken up to a greater appreciation of what you used to have before and took for granted. Just being able to walk. Just being able to get around on your own.

You’re also woken up to the everyday reality of folks who live with some form of disability all the time. How the world’s architecture isn’t very accommodating to people in wheelchairs, or people who are sight-disabled, or those who experience disability in other ways. If you’re able to return to abledness, you’re way more grateful. And you are more sensitive to the needs of people who are disabled and more willing to advocate on their behalf.

Then there’s wake-up calls which seem almost mystical in nature. You experience a physical collapse of some sort or fashion that, seen in retrospect, seems to be a highly-intentional message from the Universe to slow down, to revise your priorities, to go in quest of higher purposes.

Through some breakdown in your body, the Universe is getting your attention. God is speaking to you through Brother Ass.

All these wake up calls….

And then there’s the fourth and last kind of lesson I’ll describe today.

It’s about the nature of healing. How a person can find healing even when there’s no cure. Remember my Baba, with her terminal cancer? Then there’s chronic illness like Long Covid, or Parkinson’s, or diabetes, or fibromyalgia, or Alzheimer’s–illnesses that are not like a cold and not like gallstones and not like a broken leg in that they (chronic illnesses) are with you forever and they change your life. The very thought of it is overwhelming, and can send anyone into resentment and despair.

When there’s no cure, the goal of healing can truly seem impossible.

However, I want to share an observation from Rachel Naomi Remen, a medical doctor who specializes in the care of people with life-threatening illnesses. She’s noticed something quite surprising: how folks who are perfectly healthy (who might be out there jogging and eating all the right foods and in other ways perfect models of fitness) how these folks can sometimes be the most boring people of all. By contrast, she says, “People who are not physically healthy can seem very healthy, very alive.”

Have you ever noticed something like that?

Ultimately the point is that incurable illness can be an unlikely doorway to greater aliveness. It challenges us to get clear about the hope and the purpose that gets us out of bed each morning. Incurable illnesses push us to shift the direction of our life orientation to that of inside-out. The reverse, outside-in, is when one’s physical condition determines how our spirit will be, so if our body is ill, then our spirit must fall in line and be ill as well. But life from the inside-out is sheer triumph. It means that even where a physical illness like chronic illness or cancer or something else persists, there can still be a healing of the heart. Fearlessness can replace fear. There can be gratitude for the gifts of life, even if life is imperfect. There can be forgiveness of self, of others, of the Universe.

Infirmities without a cure become spiritual teachers that open our eyes to far more than what we thought possible. It doesn’t mean we stop feeling fear. It doesn’t mean we never feel sad. It does mean that we show up to life, every day, no matter what. One wisdom teacher says that all spiritual paths have four steps: show up, pay attention, tell the truth, and don’t be attached to the results.” We just keep showing up. That’s what we do.

Because I was so young, I never really talked with Baba about her terminal cancer. I never knew how to ask about how she saw herself, what she was going through. Had she fallen into the perspective of “I don’t just have cancer, cancer has me”? Or, was she like others who refuse this perspective, who refuse to allow cancer to swallow up all of who they are, who realize that even if their bodies have cancer, their minds and their spirits do not?

Though they might be sick physically, spiritually they are free.

During my visits with Baba before she died, I do remember moments in her basement, which was where the TV lived. There, where the 1970s shag rug was like uncut blue grass, we’d watch the evening line-up of shows. Back then it was Charlie’s Angels, Laverne & Shirley, and The Love Boat. Since it was typically right before bedtime, I’d be in my jammies and Baba would be wearing a shapeless muumuu. Her face shone with moisturizer–I think it was Oil of Olay. She’d laugh along with me at the funnier TV scenes. But she’d really come alive when it was time for Lawrence Welk. When he would say his catchphrase, “Wunnerful, wunnerful,” she’d always smile.

But it was “Tiny Bubbles” that made her sing along:

Tiny bubbles (tiny bubbles)

In the wine (in the wine)

Make me happy (make me happy)

Make me feel fine (make me feel fine)

So here’s to the golden moon

And here’s to the silver sea

And mostly here’s a toast

To you and me

Tiny bubbles (tiny bubbles)

In the wine (in the wine)

Make me happy (make me happy)

Make me feel fine

She’d sing right along, and I’d sing with her. In these moments, her cancer seemed completely forgotten.

I think she had a crush on the King of Champaign Music, actually.

And she didn’t let cancer take that away from her.

For human beings having a spiritual experience, the cancer journey must involve far more than simply excising a tumor, or treating a malignancy with radiation, or injecting chemotherapy into a vein. The journey involves far more than just that.

I will never know the path that my Baba took through her wilderness of cancer. But I will always remember her with her shining Oil of Olay face, singing about the golden moon and the silver sea and the toast to you and me.

Whatever wilderness of illness you may be going through, whether curable or not, whether yours or that of a loved one, today we are honoring this leg of your spiritual journey. We are honoring the challenges you are facing and the lessons you are learning. We are lifting you up in love and healing.

From St. Francis, all the way to me and you.

Brother Ass is teaching us.

Leave a comment