In her poem entitled “Prayer,” Daisy Rhau tells a story about her father when he was only ten years old, his life threatened during warfare in Korea, 1944. He was fleeing enemy soldiers with the rest of his family, hiding behind a burial vault in an ancient cemetery, waiting for the signal to run to the next tomb, and then the next. “I want to tell you,” Daisy Rhau says to her father,

that my life depends

on imagining

your hard boy feet, the way

they hit below sea grass,

below the packed sand that lies

the other side of this world,

in the grit of my heart.

We can all say something like this about the stories of the parents and parent-figures in our lives. They get inside us and become the grit of our hearts. If we have children and grandchildren–or if we are a mentor or otherwise respected figure in another’s life–they can equally say this about us.

“My life depends on imagining….” It starts very naturally, when we are young. We ache to know what the adults who are so central to our worlds were like before we were born, before we came to know them as mom or dad or grandma or grandpa. Especially when they were kids our age. Their secret lives, so to speak. Our aching to know is a developmental yearning, a need for a place to grow from. We’re trying to become ourselves, through imagination, and this is how it happens. Their histories are the soil, the nutrients. Instinctively, our roots reach down deep into their stories.

Take a moment to reconnect with a story about a parent that has meant much to you. Is it a story

of amazing courage, as in the case of Daisy Rhau’s father? Or maybe it’s a funny story that always cracks you up.

What has inspired your imagination?

They’re the places we grow from. Though it’s important to add that the growing is not always tidy. Our child minds can take the stories we hear and do very interesting things with them. For example: When I was young, I loved it when my dad shared tales from his Boy Scout days back in the 1950s in Alberta, Canada, roughing it in the wild with his fellow Scouts. One time, he taught me the lyrics to a song they’d sing around the campfire at night time, under the stars, fire spitting and hot:

99 bottles of beer on the wall, 99 bottles of beer, take one down, pass it around, 98 bottles of beer on the wall.

98 bottles of beer on the wall, 98 bottles of beer, take one down, pass it around, 97 bottles of beer on the wall.

97 bottles of beer on the wall, 97 bottles of beer, take one down, pass it around, 96 bottles of beer on the wall.

It got absurd really really fast. So many bottles of beer.

I thought it was hilarious.

It also became an earworm. That’s when a song gets stuck in your head, and it repeats involuntarily.

There I am, in first grade class, and I’m doing a worksheet, and I’m humming a song about drinking ginormous amounts of beer….

But it was a piece of his life that I could actually have. I wasn’t myself a Scout, and I don’t think I’d ever experienced a real campfire before, especially under the stars. I was also a fairly solitary boy, a book reader, caught up in daydreams. Furthermore, dad was a workaholic and though I might have spent a lot of time in the doctor’s lounge at his clinic, I didn’t really see him all that often. Outside of work, he was busy with chores. He was just busy.

As for my mom: she was no friend of the outdoors. Her preference was to be in neat and tidy air-conditioned environments.

I wanted my own experience of the wild. No one was helping me with that.

So I came to a decision, when I was around six years old. I’d make my own campfire. It happened to be a Saturday, I was at home, and I seem to recall that mom wanted me to stay indoors.

Indoors my campfire would be.

The only problem is that I didn’t have access to the normal stuff of campfires: sticks and twigs and leaves. However, close at hand were items that were sort of stick-like. I’m talking about Crayola crayons.

I had lots of them at my disposal.

When I was sure mom was busy upstairs and out of sight, I used those Crayolas to build a teepee-like structure, as I’d seen the cowboys on TV’s Gunsmoke do it. I ripped some pages out of one of mom’s Better Homes and Gardens magazines, tore them up, and used her cigarette lighter to get the fire going.

Right on top of the living room carpet, which was classic 1970s mustard yellow shag.

I fed the mouth of that Crayola crayon teepee structure like it was positively hungry. The flames grew. The vivid Crayola colors bubbled and flowed.

As I took in the whole glorious scene, I happily hummed the song dad and I would sing: “99 bottles of beer on the wall, 99 bottles of beer….” In my own mind, I’d become a genuine Boy Scout!

I’d gotten to maybe 95 bottles of beer and then, suddenly, mom was there snuffing out my beautiful campfire, screaming some very bad words. My fantasizing came to a screeching halt, and I saw what I’d actually done. The Crayola colors had melted into a clump of brownish black and were already solidifying down into the shag rug fibers.

I’d just ruined the carpet.

That this would be the result of building my own campfire in my own special way hadn’t occurred to my six year old brain. The next few hours were torture, with mom repeatedly yelling at me to wait, just wait until your dad comes home, and I truly feared for my life. I was ready to run. But when he finally arrived and saw what I’d done, strangely enough, he just seemed sympathetic. He just said, “Don’t play with fire anymore, son”—and then added, “indoors.”

As for Mom, she got a new coffee table, the one she’d been wanting for a while. Placed right on top of the ugly burn spot, the living room looked spotless, as if it had never been, at least for the briefest of moments, a campfire scene in the wild.

It’s a cautionary tale I tell. Still, I’m so grateful dad shared his Boy Scout stories. Our lives depend on imagining. The secret lives of the important adults in our world are so powerful, and we need them to be. We need a place to grow from.

The nature of this need changes, however, as we age. As I grew into adolescence and then into my twenties, the need fell to an all-time-low. Which makes sense developmentally, because at this time you’re trying to nurture your roots in your own soil which is mixed and mingled with the soil of your peers as well as that of popular culture including your favorite musical artists. You’re trying to firm up your own sense of identity separate and apart from your parents and other parent figures.

If they have secret lives, good: let them stay secret.

But the seasons of life cycle onward. Until there came a time in my own life when this hunger to know stories about my parents returned, and I felt it more sharply and keenly than ever before.

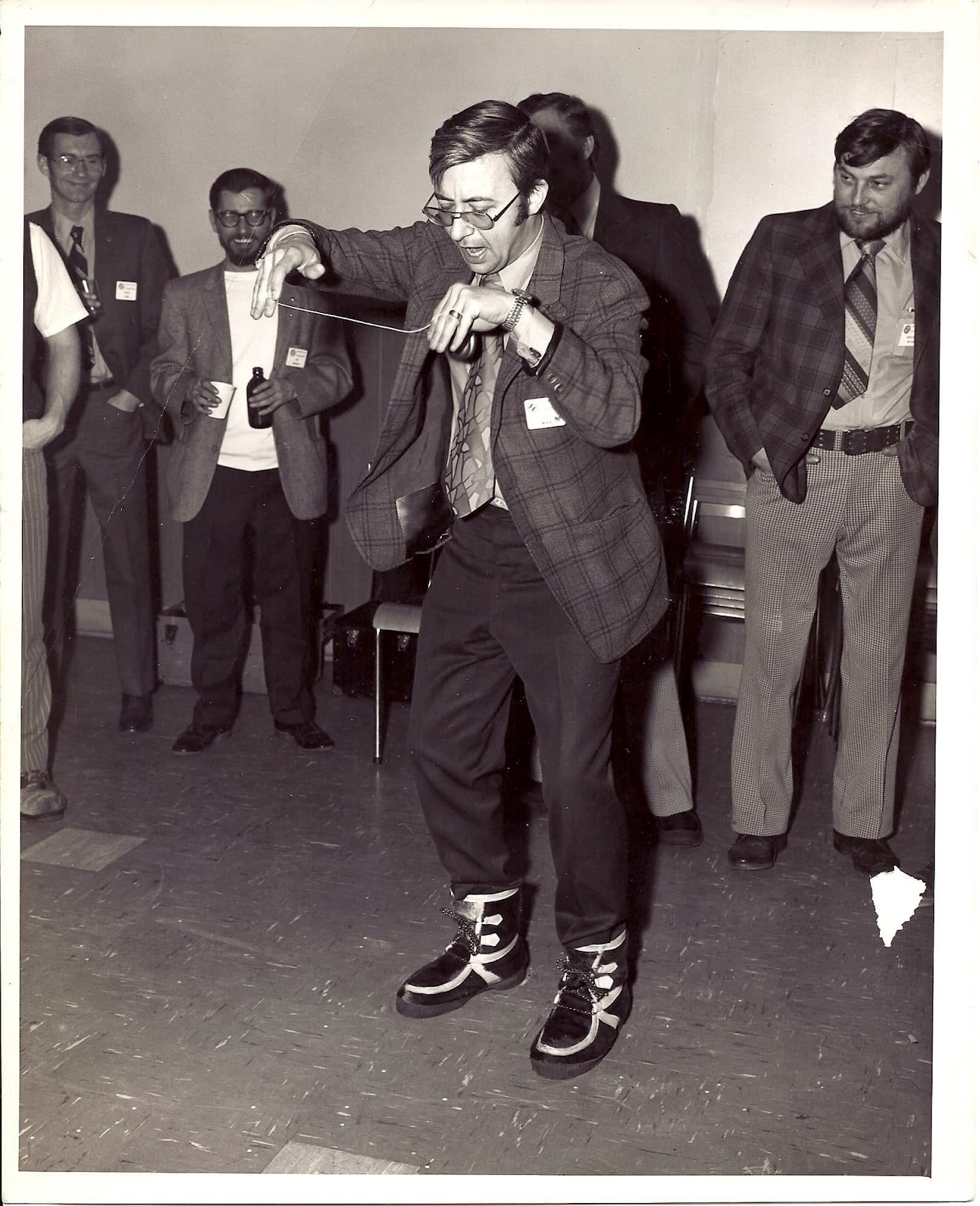

The hunger’s return was connected with the discovery, back in 2001, of this photograph.

My dad’s the guy in the center, showing off his mad yo-yo skills. It was probably taken in 1974—something like that. Check out those 1970s fashions. From my dad’s boots, you can tell it was wintertime in Northern Alberta.

When the photo was taken, I was around seven years old. And maybe back then I knew about Dad’s hijinks with yo-yos, but over the years, I had completely forgotten, until the day the photo surfaced, when I was 34 years old facing one of the saddest days of my life, because it was a day when I was going through the ritual of sifting through a dead parent’s things.

Dad had died unexpectedly. He was only 60. The funeral had taken place the day before. I was in his study, surrounded by the silent witness of his things. A shelf full of hundreds of editions of classic works of history and literature, leather bound, from Franklin Mint. Hand guns in his desk drawer. Shotguns in his closet. A big, messy pile of papers, and on one of these papers I discovered a list of personal aspirations he had made for himself, to lift himself out of the despair he felt and had been feeling for years. It was all so removed from the playfulness reflected in his yo-yo picture.

I saw all these things and more.

The hunger to know this man, which had been at an all-time low, returned with a fierceness that astonished. But now the underlying motivation wasn’t about finding a place to grow from. I already had that. Now, I found myself wanting to know who my dad was, not because he was a God to me and I wanted to bask in that glory, but because he was a human being who, like all human beings, try to do the best they can.

The flawed human being I was wanted to connect with the flawed human being he was.

By the time he died, I had gone through enough living to get a firsthand sense of how life can hurt you and wear you down, as it had him. But how had Dad experienced that, and what did he do? The mistakes he had made—how might they speak to some of mine? “Daddy, tell me your best secret,” says the child to his father in a poem by William Stafford, and the father replies, “I have woven a parachute out of everything broken; my scars are my shield; and I jump, daylight or dark, into any country, where as I descend I turn native and stumble into terribly human speech and wince recognition.”

Moving forward, my life depended on imagining that. That’s the answer I was ready for, now that I was an adult. Seeing my dad’s parachute he’d woven out of everything broken; witnessing how he’d jumped into the complexities of his life, turned native, and stumbled….

But there were no answers coming, as I sat there in my dad’s study, sifting through his things. The only things coming were questions, fast and furious. Dad, why did you have so many guns? What did that mean for you? Why did you have an entire library full of leather-bound classics but you never read any of them, or at least only very few? Whatever happened to the playfulness and joy I saw in your yo-yo picture?

All these questions coming up, and the only person from whom answers could come was gone.

This morning I grieve this lost opportunity, but I also grieve the lost opportunity for my dad. Storytelling is not a one-way street. As adults we need to be telling our stories, and when we do not, the harm is irreparable. Not just to our children, whatever their age happens to be, but to ourselves. Psychologist Erik Erikson became famous for identifying the main challenges that people typically face at points across the lifespan, and he identified the main challenge of mid-adulthood as finding a way of making a positive contribution to the world. Telling your stories is part of that. Do it, or else you stagnate.

Older adults, says Eric Erikson, face a different challenge, and that’s coming to terms with their history and asking, “What kind of life have I lived?” “What wisdom have I learned?” “How did I stay hopeful and persist during times of social crisis and war?” Telling your stories is also a part of that. Do it, or else you fall into despair.

It doesn’t have to be hard! The stories want to be told. They want to be completed through the telling. The 2003 classic movie entitled Secondhand Lions illustrates this. Dr. Google summarizes the movie plot as follows: A shy adolescent boy named Walter (Haley Joel Osment), is taken by his greedy mother to spend the summer with his two hard-boiled great-uncles, Hub (Robert Duvall) and Garth (Michael Caine), who are rumored to possess a great fortune. At first, the two old men, both set in their ways, find Walter’s presence a nuisance, but they eventually warm up to the boy and regale him with tall tales from their past. In return, Walter helps reawaken their youthful spirit.

Early on in the movie, the Haley Joel Osment character finds the key to a trunk covered in stickers from far away places. He’s struck by the contrast between this exoticism and the great-uncles he’s only recently been introduced to who seem to be nothing but country-bumpkin farmers. He opens the trunk and he finds a picture of a beautiful woman. It’s a mystery–who is she? Then comes a startling sound, from outside his room. The boy goes to investigate, only to see one of his great-uncles, the character played by Robert Duvall, called Hub, shuffling forward in his nightdress, carrying a plunger like it was a rapier. The old man is sleepwalking. He’s fighting old swordfights in his sleep. He’s slashing away at invisible enemies.

Next morning the boy and his great-uncles sit around the breakfast table, and Hub complains about soreness in his back and shoulder, saying that the new mattress isn’t working. He’s totally oblivious to how the stories won’t let him alone until he tells them faithfully and fully, for this is what his stage of life wants from him. Tell the stories, or fall into despair. As for the boy, who needs a place to grow from, he can’t help but ask: “So, you two disappeared for forty whole years—where were you?” and Hub just shuts him down, growls, “We’re old men, washed up. That’s old history, dead and done.”

But we know it’s not dead and done, not at all.

Can you relate to the sleepwalking scene? Do you have secret stories in you that rattle around, want to be completed through the telling, and won’t leave you alone?

Often we don’t know, unless we just start talking. Often the really important stories bubble up in the middle of others, grip you with an urgency that surprises. Tell one story, and this act of remembering triggers more remembering, more stories. “Oh, I don’t know, I don’t remember” becomes “Oh yeah, something else occurred to me.”

One story I would have loved dad to start talking about had to do with his relationship with his own father. When I knew my grandfather (my dido), he had his gruff moments but he was generally loveable. I remember one time when I enthusiastically said to my dad that dido was such a fun guy, and dad paused for a moment and said, “He wasn’t so fun back when I was a kid.”

But that was it.

I wish he’d kept talking.

Years later, after dad’s death, I came to learn that dido at times could be positively brutal. My dad, as the yo-yo picture suggests, had a streak of zaniness to him, and as a teenager, one form this zany streak took was a mad-scientist obsession with chemicals. Creating “reactions.”

In other words, blowing stuff up.

One day, he decided to get back at his older sister for something. He planned to create a small chemical reaction in her bedroom—a tightly controlled explosion and burn. Something like that. Well, as in the campfire episode from my own childhood, that anything more could have happened just hadn’t occurred to him. He ended up destroying her bed and several pieces of furniture.

But the truly horrible part of the story is what happened when his dad (my dido) came home from work and found out. Dido went straight to the garage and got his axe. He returned to the house and, in a chillingly cool voice, said that he’d had it, enough’s enough, the kid is going to die. At which point dido lunged after my dad. Dad dodged his own father and bolted straight out of the house and ran for his life. He wouldn’t return until he was sure that his mother (my baba) had sufficiently calmed dido down and made him promise to stop.

No one in this story was laughing. There was no fun to be found.

And this had not been the first time dad had been terrorized by dido.

What must that have been like, to carry a memory like this throughout your life? Your own dad chasing you with an axe? How had his heart been broken, from running like this?

I wish dad had kept talking. All I know is that in my own campfire episode, dad’s response to me was 180 degrees different. Our parents try to do better than was done to them, and so do we. We do the best we can.

Last Sunday was Father’s Day, and several weeks before that, it was Mother’s Day. There are two things parents can do to honor both days all year long. One is to tell our stories. Don’t be like Hub in the Secondhand Lions movie and shut the boy down when he asks, “So, where were you for 40 years?” For your own sake, if not for his, tell him where you were. Tell him what you did, what you yearned for, what you achieved, what you failed at, what you hoped for, what you feared.

You may remember Randy Pausch, the Carnegie Mellon University professor diagnosed with fatal pancreatic cancer. He became instantly famous for what was called his “Last Lecture,” delivered in 2007 even as he was actively dying. At one point he was asked about passing on the essential parts of himself to his children. “If you had six months to live,” went the question, “where would you begin with your children?” And Randy Pausch answered, “Don’t tell people how to live their lives. Just tell them stories. How they apply—they’ll figure that out for themselves.”

The U.S. just bombed Iran. Who knows what this will mean.

If you’ve been through wars before, tell your stories. How did you hold up? How did you make it through?

Just tell the stories. That’s one thing we can do to honor Mothers and Fathers Day all year long. As I say this, I need to acknowledge that some of us are estranged from our children. It’s so painful. But there are other children who will listen. There are other people who will use your stories as places to grow from even if you don’t share DNA. Love isn’t necessarily about shared DNA. Families of choice transcend all that, thank God.

And then there’s this, a second thing we can do: ask. Ask to hear them from the important adults in our own lives, no matter how old we are. Don’t wait, until all that’s left is the silent witness of mere things, and the one person who could answer your questions is gone.

For myself, today, I’m carrying in my heart the picture of my dad playing with the yo-yo. Life can hurt you and wear you down, and it did that to him. Yet there is triumph in being able to choose the stories we emphasize going forward.

Thanks, dad, for not killing me when I ruined the rug.

Thank you for teaching me the bottles of beer song.

You weren’t perfect. No parent is. But thank you for giving me a place from which to grow.

Thank you for your stories.

Leave a comment