Summers when I was a teenager, I used to teach Vacation Bible School at the Church of Christ in Palestine, Texas. We used popsicle sticks to create little Noah’s Arks. We played Pin-the-Animal-to-the-Ark. We ate a snack of animal crackers. It was a blast.

It might not have looked like it, but we were doing theology. We were reinforcing a certain understanding of our big picture relationship to the world and to each other. That’s what my Vacation Bible School kids and I were doing, those sweet summer days.

It all came back to me recently when I watched Daniel Aronofsky’s epic Bible drama entitled Noah, on Netflix. But only by sheer contrast, because there was nothing at all sweet in that movie. Watch it and you are plunged into a world that has turned depraved. God in that story is all-powerful (or “omnipotent,” as the technical, theological term would put it), which means He could have intervened in the ages before Noah to prevent this, but He didn’t. He chose instead to intervene in Noah’s time, when the world was already way past the tipping point, and his intervention took the form of a world-wide catastrophe.

Lots of screaming in that movie. Practically all life was destroyed through a massive flood which is what the Bible says happened. Noah and his family suffer each moment of the story as it unfolds. As for God–the movie symbolizes the Divine as a grey sky churning with clouds, to which Noah continually lifts his eyes, pleading for help, pleading to understand, but no answers come. The mysterious grey skies just churn away. God is untouched by the suffering.

God is above it all.

This is what I call theology inside the box. I was in that box during those sweet Vacation Bible School days but didn’t really know it. I started waking up, however, when my Dad died miserably at just 60 years old and I lifted my eyes to the same churning grey skies that Noah might have lifted his eyes to, and I pleaded for help and pleaded for understanding like Noah did, and none of it came my way. God could have intervened so that my Dad could have beaten his addictions and illnesses, but God did not intervene. God was a greedy miser with all his ultimate power–a Scrooge, a Grinch.

You see, this is the problem with the God of my Church of Christ Vacation Bible School, the God of the movie Noah, the God that pervades Western theological history, and the God that tends to leap to imagination whenever the word “God” is spoken. It’s all one and the same. This God is abusive. Liberal theologian Robert Mesle puts it like this: “In the Bible, and in much of Christian thought, God has been described as directly willing and causing great evils: war, slavery, plague, famine, and even the hardness of human hearts. At the very best, God has been depicted as standing by and allowing needless suffering that ‘He’ could easily have prevented.” Robert Mesle goes on to say, “To defend our ideas of God, we are driven to turn our ideas of good and evil inside out to explain why it is really good for God to allow such great suffering.”

One specific example of having to twist up our reasoning into pretzel shapes to defend the traditional idea of God relates to the pervasive social problem of poverty. Poverty has always existed and will always exist. Well, it must mean that it’s all a part of God’s plan, and who are we to fight against God? So let’s all vote for politicians who support public policies that rob from the poor and give to the rich.

Some people really go there. That’s their line of thinking. That’s what theology inside the box can lead to. Right and wrong turned inside out.

I am tired of theology inside the box. Are you?

And in fact, a lot of us are. A couple years back, New York Times writer Eric Weiner used the opportunity of the oncoming Christmas holidays to raise the question of what he called “the sad state of our national conversation about God.” “For a nation of talkers and self-confessors,” he writes, “we are terrible when it comes to talking about God. The discourse has been co-opted by the True Believers, on one hand, and Angry Atheists on the other. What about the rest of us?”

That’s another consequence of theology inside the box. It’s polarizing. True Believers who refuse to question the Vacation Bible sweetness of their God concept, and the Angry Atheists who are equally committed to the Vacation Bible God concept but reject it absolutely.

But what about the rest of us? “The rest of us,” says Eric Weiner, “turns out to constitute the nation’s fastest-growing religious demographic. We are the Nones [N-O-N-E-S], the roughly 30 percent of people [as of 2025] who say they have no religious affiliation at all. [Of this 30%, the great majority–69%–are younger people under 50.] Apparently, a growing number of Americans are running from organized religion, but by no means running from God. On average 93 percent of those surveyed say they believe in God or a higher power; this holds true for most Nones.”

And then Eric Weiner says this, which brings us closer to our topic for today about theology outside the box: “Nones [he says] don’t get hung up on whether a religion is ‘true’ or not, and instead subscribe to William James’s maxim that ‘truth is what works.’ If a certain spiritual practice makes us better people—more loving, less angry—then it is necessarily good, and by extension ‘true.’”

What do you think about what Eric Weiner is saying? Does it ring any bells for you, as you sit in the pew of a Unitarian Universalist church which does indeed seek to be an organized religion but one that isn’t at all traditional?

Personally, I find myself persuaded by the idea that “truth is what works.” It’s not good enough for me to believe something just because an authority figure tells me to, or because it’s endorsed by the crowd. If a God concept confuses right and wrong, if it is socially divisive and polarizing, if it walls you off from your life rather than helps you engage it more creatively, then that God concept is going in the wrong direction. But if a God concept illustrates the true meaning of love and compassion, if it helps create common ground among differences, if it turns you into someone who has Holy Curiosity, if it brings you into true abundance and hopefulness in your life—well, that’s what I call “it works.”

Having a sense of humor about the whole religion thing is also evidence of things working. Holier-than-thou pridefulness is always part of the problem and never the solution. Writer G. K. Chesterton hit the nail on the head when he said, “It is the test of a good religion whether you can joke about it.”

Here’s a joke that has us knocking on the door of theology outside of the box. It’s called, “God will save me.” A big storm approaches. The weatherman urges everyone to get out of town. The priest says, “I won’t worry, God will save me.” The morning of the storm, the police go through the neighborhood with a sound truck telling everyone to evacuate. The priest says, “I won’t worry, God will save me.” The storm drains back up and there’s an inch of water standing in the street. A fire truck comes by to pick up the priest. He tells them, “Don’t worry, God will save me.” The water rises another foot. A National Guard truck comes by to rescue the priest. He tells them, “Don’t worry, God will save me.” The water rises some more. The priest is forced up to his roof. A boat comes by to rescue the priest. He tells them, “Don’t worry, God will save me.” The water rises higher. The priest is forced up to the very top of his roof. A helicopter comes to rescue the priest. He shouts up at them, “Don’t worry, God will save me.” The water rises above his house, and the priest drowns. When he gets up to heaven, he says to God, “I’ve been your faithful servant ever since I was born! Why didn’t you save me?” And God replies “First I sent you a weatherman, then I sent the police, then I sent a fire truck, then the national guard, then a boat, and then a helicopter. What more do you want from me!!??”

That’s the joke, and before I show how it illustrates outside-the-box theology, I better do my job and tell you that this outside-the-box theology has a name: “process theology.” Historically, much of process theology is home-grown; it emerges out of Unitarian Universalist thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, who spoke of the “deep power in which we exist, [how] when it breaks through our intellect, it is genius; when it breathes through our will, it is virtue; when it flows through our affections, it is love.”

Then there is the great Unitarian Universalist theologian of the 20th century, Charles Hartshorne, who titled one of his books Omnipotence and Other Theological Mistakes.

And then, finally, there’s the father of Process Theology himself, not a Unitarian Universalist but, says Wikipedia, a “friend”: the brilliant Alfred North Whitehead.

Listen to something Whitehead said: “When the Western world received Christianity, Caesar conquered, and the received text of Western theology was edited by his lawyers… The brief [vision of humble and patient love that came from Jesus] flickered throughout the ages, uncertainly … but the deeper idolatry, the fashioning of God in the image of the Egyptian, Persian, and Roman imperial rulers, was retained. The church gave unto God the attributes which belonged exclusively to Caesar.”

That’s exactly why the priest in the joke does what he does. Why he constantly refuses help. Why he’s so upset with God in the end. God is supposed to barge into history like an imperial, all-powerful Caesar, to intervene supernaturally. That’s the kind of power the priest is convinced God has. Hard power to force things. Hard power that is coercive and violates natural laws and people’s freedom. The priest is stuck on this idea of power—even though, as Whitehead suggests, Jesus himself offered people a completely different sense of divine power: power that is persuasive and patiently but steadfastly calls people to a better vision of life, which they can follow, but only if they choose to do so.

The joke takes the side of Jesus. And Whitehead.

The priest in the joke never got it. But we can.

I won’t speculate on how Jesus came to this conclusion about God. But as for Whitehead, he came to it in big part because of the findings of the most successful and battle-tested theory in all of contemporary science: quantum mechanics. The fundamental particles that make up everything, says the physicist Werner Heisenberg, “are not real; they form a world of potentialities or possibilities rather than one of things or facts.” In the case of Noah, it’s only when he chooses to build the Ark that a certain direction into the future begins to be born. Before his choice, no one–not even God–can know with absolute certainty what will happen. God’s knowledge of fact is as limited by the laws of quantum mechanics as ours is.

The main problem with the priest in the joke—and with people who are still IN the theological box—is that they conceive of God as absolutely unlimited in knowledge and in power. God’s some kind of super person whose hands are just like ours but bigger and stronger. We use our hands to direct the affairs of our lives, and God uses God’s hands to send all the animals, two of every kind, into the Ark.

Think like this, and you will drown. You will wait for God to come save you. All sorts of real help will come by, but you’ll ignore it. And you will drown.

We’ve got to turn from that, and turn to theology OUTSIDE of the box.

Process theology: here are the basics.

First: the world is God’s body. Everything is part of God, in God.

“For me,” writes Herman Hesse, “trees have always been the most penetrating preachers.” Of course. Because trees are a part of God’s body, and so are stars, and so are rivers. Humans are too, but Process Theology is not human-centered. Everything is a part of God, everything needs to be honored and cared for, not just people.

Second: even though the world is in God, the parts in our world (including you and me) have creative independence and freedom. Consider your own body, for example, when it gets sick.

Your mind doesn’t want it to be sick, but your body clearly has independence because it gets sick anyhow, despite what you want, and you have to cope. Same thing with God. God doesn’t want the world to be sick, and yet the world has creative independence. God simply can’t enter into the world supernaturally, like a bull in a china shop, and stop this and start that.

No wonder all the prayers begging God to turn things around for the Cleveland Browns fall flat.

Third: God is more than the world. God is the knower. Part of this includes possibility. God knows every possibility there is to know. There is no possible world that God is ignorant of. But possibility is not the same as actuality. Like everyone else, God can know about facts only when choosers collapse the spectrum of possibilities before them into the single reality of what they do. Again, God is as constrained by the laws of quantum mechanics as we are. God can be disappointed. God can be delighted.

God can also be affected. God is never “above it all.” God feels things through God’s individual creations. The Olympic runner Eric Liddell said, “When I run, I feel His pleasure.” The figure skater I am, at the ripe age of 58, has plenty of pains in his body which God also feels.

This affirmation of Process Theology is particularly surprising when you set it side-by-side with the traditional, in-the-box idea of God as some kind of imperial Caesar supreme and worthy of worship because nothing bothers him, nothing moves him, he is permanently unchanged and unchanging. Process theology disagrees vehemently. Such a being is a fiend. For God to truly be worthy of worship, God must know how life feels. God must know what it’s like to be the grasses of a plain, the trees of a forest, the bird as it soars, the ocean as it sighs, and humans as they live. God must be absolute in empathy and rapport to be worthy.

God, writes process theologian Carter Heyward, “will hang on the gallows.”

God will inspire, fill, overwhelm [the musician] Handel with power and splendor.

God will be battered.

God will have a mastectomy.

God will experience the wonder of giving birth.

God will be handicapped.

God will run the marathon.

God will win.

God will lose.

God will be down and out, suffering, dying.

God will be bursting free, coming to life.

God will be who God will be.

For me personally, it means that, when I am frustrated, I hesitate not an instant to cuss up a blue streak when I pray to God. All the bad words. Oh yes. God understands. God is not a prim, self-satisfied moralist who doesn’t know what it’s like to screw up, who is judgmental, who hasn’t a clue about what real confusion feels like, or hurting others, or being hurt. This is not a Church of Christ Vacation Bible School God. This is a God for real, gritty, adult life.

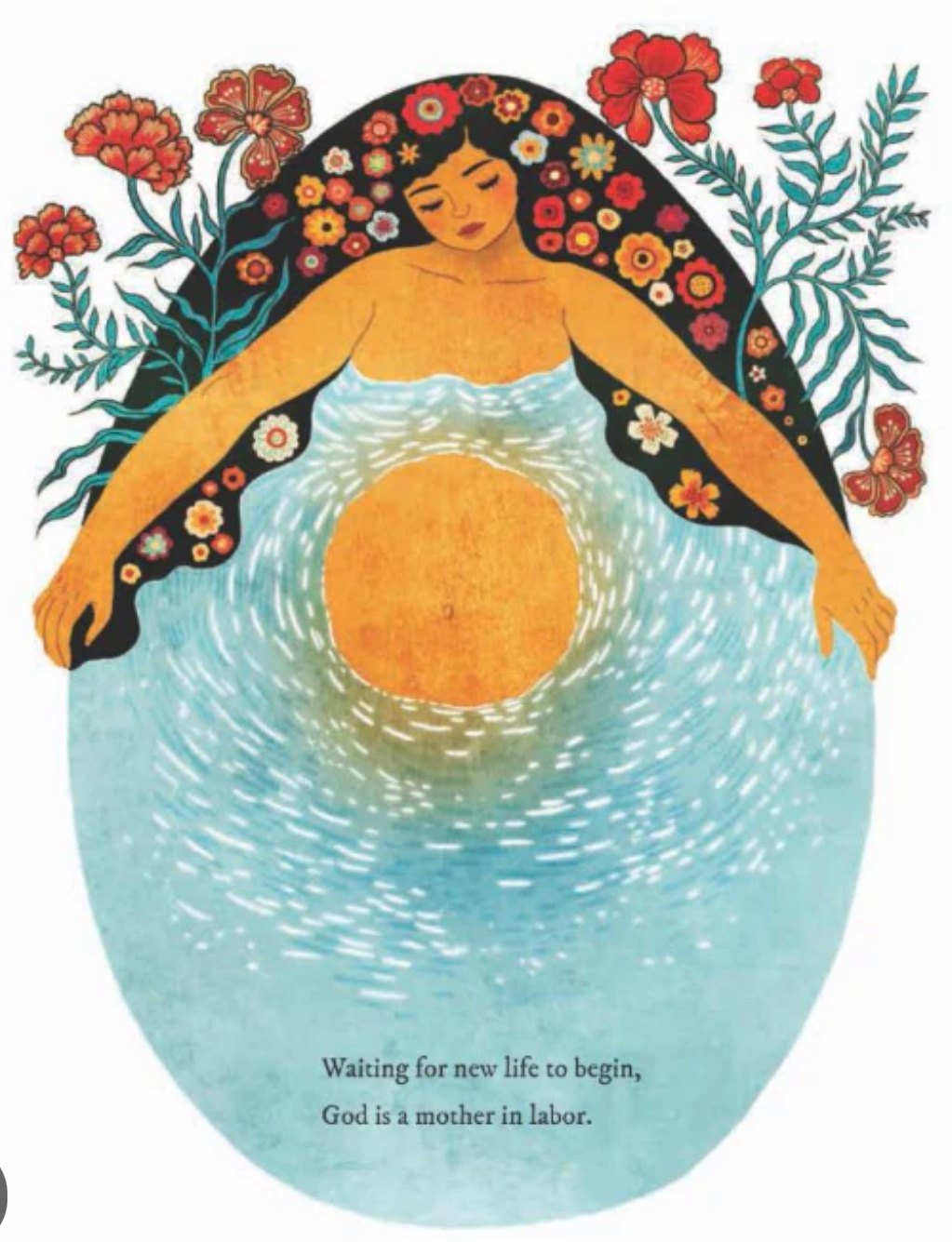

These are three of the main ideas of process theology, then. (1) The world is in God, (2) the world has creative independence from God, and (3) God is more than the world. Here’s a picture of this, worth a thousand words:

From Mother God by Teresa Kim Pecinovsky (Author), Khoa Le (Illustrator)

Mother God, Father God. Creation is the baby being born, endlessly. And now a fourth, final process theology idea, the last I’ll mention today. In every moment, in every place, constantly, God calls us towards the better possibilities of life. God does it because God is Love; and God is uniquely suited for it because God knows how life feels, knows everything about us, is far more compassionate about our flaws and limitations than we ever could be towards ourselves.

The question is never, God, are you with me? The question is always, Am I with God? Am I using my freedom to position myself in a way where I can feel God’s constant, faithful call? “When it breaks through our intellect, it is genius; when it breathes through our will, it is virtue; when it flows through our affections, it is love.” That’s Emerson, again. God’s call to us is to become more than we ever thought possible. But we must choose to align ourselves to God’s call. We must learn how to listen, through meditation, through prayer, through moments of solitude in nature as we listen to the preaching of the trees, and in other ways.

Sometimes, though, when we hear the call, it can scare us to death. We are called to go out from the place with which we are completely familiar but it no longer serves our highest good and that of the world’s. We are stuck. But God calls us out. And it can scare us to death. And so therefore we deny, we delay. But God is not some imperial Caesar. God’s style is just not authoritarian and holier-than-thou. God just keeps showing us the vision of what is possible. God longs for it, and we can feel that longing….

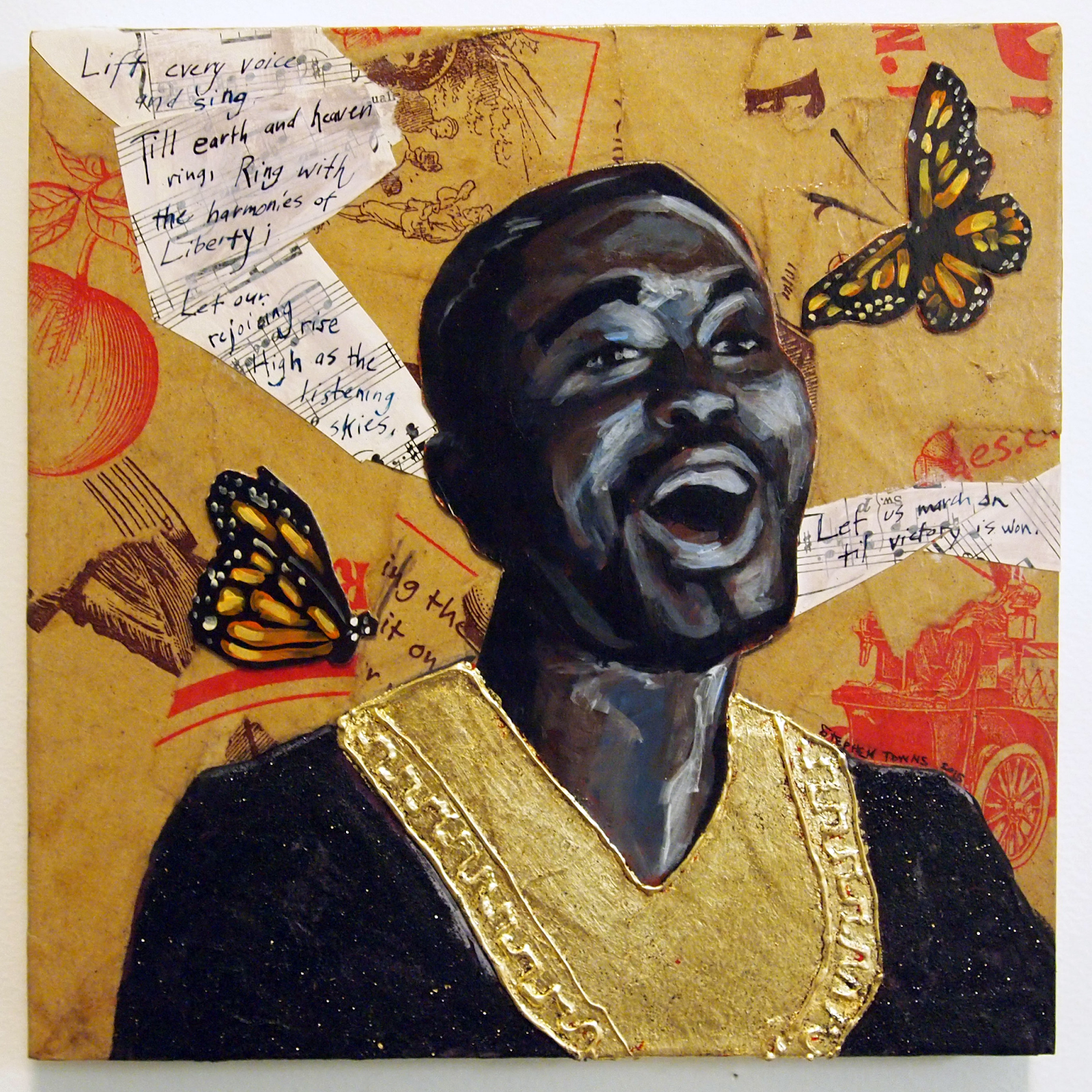

Sing it with me, this song from the pen of James Weldon Johnson, number 149 in your hymnal. Just the first verse.

Lift ev’ry voice and sing,

Till earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty;

Let our rejoicing rise

High as the list’ning skies,

Let it resound loud as the rolling sea.

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won.

Do you feel that? That deep feeling of desire for a better world? If that song stirs powerful feelings in you, process theology would say that you are tapping into the feelings of God right this very moment. It’s one reason why music is precious—it can tap us straight into God. And here, what we feel is God’s thirst for justice. How God sees all the ways in which the world could be better, could be healed, and God wants it.

Lift every voice and sing!

But there are no hands but our hands. God doesn’t have hands. We do. That’s what we are for.

This never crosses the priest’s mind, that priest from the joke. That the weatherman, the police, the fire truck, the national guard, the boat, and also the helicopter all represent ways in which people responded to the call to serve and protect, which is about Love, which comes from God. Never crosses his mind. The priest wants God to reach inside the physical universe with a big God hand and scoop him out.

But that is theology IN the box.

God doesn’t have hands. We do. That’s what we are for.

The Catholic saint Teresa of Ávila put it beautifully like this:

Christ has no body but yours,

No hands, no feet on earth but yours,

Yours are the eyes with which he looks

Compassion on this world,

Yours are the feet with which he walks to do good,

Yours are the hands, with which he blesses all the world.

God is singing to us every day, every night, every moment, singing us forward into greater things, singing love, singing courage.

And it is up to us to listen, in our freedom, and to sing back.

Leave a comment