Jesus Saves!

As I say that, what’s your immediate reaction?

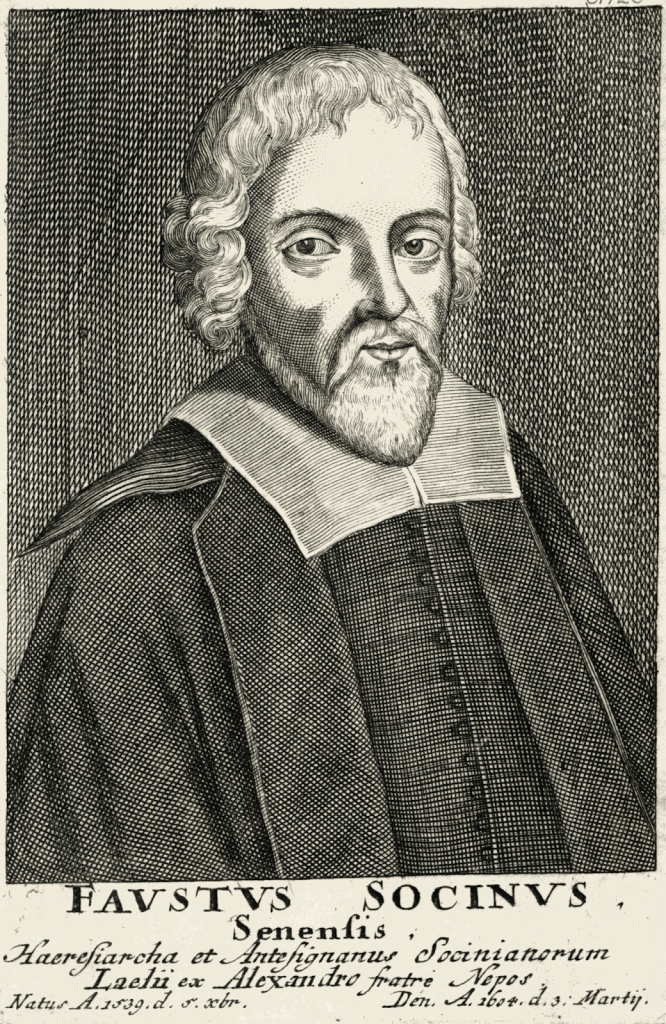

Hold on to it, now, as I take you back 500 years ago to the thought of a Polish theologian named Faustus Socinus.

He believed it. He believed that Jesus saves. But now lean in and listen carefully. Faustus Socinus believed that Jesus saves but not by virtue of his death. None of this “blood of the lamb” stuff for him.

Quite to the contrary, Faustus Socinus believed that Jesus saves by virtue of his deeds. It’s the moral and spiritual example of how he lived his life that has salvation power, to the degree it inspires us to live as he lived and love as he loved. To love thy neighbor. To love even thine enemy.

Gospel stories are good news precisely because they show the way to spiritual aliveness in the here-and-now.

Another thing Faustus Socinus had to say about salvation addresses the question of what happens after a person dies. God is good, he believed. But what proves this goodness is that God won’t allow any soul to endure eternal torment and hellfire. It’s why Jesus said in the Gospel of John 12:32: “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.” No one will be left out of that loving embrace. Furthermore, in parable after parable, Jesus spoke about ultimate reconciliation with God, no matter how bad a person is. In the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32), for example, the wayward son is restored, not cast away.

I mention Faustus Socinus precisely because he sings a different tune than what we might be used to, or what we’ve been taught to believe, about Jesus and salvation. Following Jesus’ example in our own lives, through works of justice and love. Trusting ultimately in God’s goodness to bring everyone into an afterlife of sweetness despite any failings and mistakes.

Salvation as a here-and-now process, and salvation as an afterlife end-state.

But that was five hundred years ago. Where does the current theological landscape look like, at least in religiously liberal spaces like ours?

Honestly, the issue might not even come up. I mean, salvation talk is rare in these parts. Just how many times in this space in the past 50 years do you think people have been asked, seriously, Are you saved?

Are you saved, brother?

Are you saved, sister?

Are you saved, friend?

When I opened the sermon and announced Jesus Saves! you should have seen the look on your faces!

The closest religious liberals might come to talking about salvation (and its opposite, sin) is in a humorous vein. One of my clergy colleagues likes to say, “I believe in Original Sin. The more original the better.” Another tells the story of receiving a certain gift from a member of her congregation. It was a box of “Wash Away Your Sins” towelettes.

The general instructions read:

- Carry towelettes with you at all times;

- Cleanse thyself before saving others;

- Stay alert to sins as they happen;

- Approach sinner;

- Offer-up a Wash-Away Your Sins towelette;

- Remain focused and ready to do it again.

Earnest sin and salvation talk, in other words, just makes us laugh.

What would Faustus Socinus say? How would we explain ourselves? How have things changed so much in 500 years?

Well, part of the explanation would point to Faustus Socinus’ own theology and that of the long line of successors following him. It’s taught us something about God and something about ourselves. It’s taught us that, first of all, the universe is ultimately safe. God’s not a bully just waiting for us to mess up so he can swoop in and crush us. Second of all, people are sons and daughters of God, and why would the good Cosmic parent throw a child away?

Both insights are things we can’t be untaught. They are in the air, in the walls. We repeat them, furthermore, through our current denominational statement of Unitarian Universalist values, approved back in 2024. They are more neutral-sounding, for sure, but Socinus’ heartbeat can still be heard in them. Statements like: “We honor the interdependent web of all existence and acknowledge our place in it.” “We declare that every person is inherently worthy and has the right to flourish with dignity, love, and compassion.” “Love is the power that holds us together.” The cumulative effect is existential comfort, not anxiety.

So of course we Unitarian Universalists today are not going to be sweating bullets about our mistakes. Of course we are not going to be overly anxious about the eternal state of our souls. Why would we?

I wouldn’t be surprised if the originator of the Wash-Away-Your-Sins towelette idea was a Unitarian Universalist.

Faustus Socinus, it’s your fault! (THANK YOU!)

So that’s one part of the explanation for the absence of earnest sin and salvation talk among us.

Another part of the explanation must be the distance we’ve traveled in five-hundred years, from a culture that rested in the certainty of one religious vision to our culture which knows many visions and must work hard to create common ground.

500 years ago, Christendom reigned in Europe. Yes, there were varieties of Christianity, but everyone still bowed the knee to Jesus Christ and the Bible. (The notable exception to this was European Jewish communities, and this story–so fraught with complexity and suffering–is its own sermon.) Now, the scene is firmly and thoroughly pluralistic. Once geographical borders were defeated by technologies of travel and communication, all sorts of ideas of salvation came up for grabs, from India and China and elsewhere. All sorts of visions emerged, together with terminologies that are intriguing to our ears.

Here are just some of them:

From Hinduism, we learn that salvation is release from samsara, or the seemingly endless round of reincarnations that individual souls experience. Samsara remains firmly in place because of something called karma, which is an impersonal and universal moral law which states: Make a mistake, and you must pay. Karma ties us to earth; and so the way of liberation is to loosen the ties. Do that by pursuing one of the four yogas or spiritual paths; which one depends on your personality type: the path of knowledge, the path of love and devotion, the path of selfless action, and the path of psychophysical exercise.

For roughly 800 million people, this is salvation.

But now consider Buddhism and its Four Noble Truths: (1) life is suffering, (2) suffering is caused by self-centered craving, (3) the nirvana experience extinguishes self-centered craving and thus suffering, (4) the way to nirvana is the Eightfold Path, which is a middle way between the two extremes of asceticism and hedonism. The Eightfold Path consists of pursuing Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. Follow the Eightfold Path, and it will take you into Nirvana.

For roughly 400 million people, this is salvation.

But now consider yet another vision: it comes from Taoism. The Tao in Taoism is the order and harmony of nature, and it is far more stable and enduring than the power of the state or the civilized institutions constructed by human ingenuity. Suffering happens when people are out of sync with the Tao, and life is like swimming upstream; but when we are in sync, all is flow, we flourish, we are effortlessly beautiful, energy (or chi) pulses through us. Taoists call this state of being wu-wei (which means no-action, or action modeled on nature).

This is salvation, for 20 million people. (Actually, for probably hundreds of millions more because the vision of the Jedi Knight that comes from the movie Star Wars echoes the Taoist wu-wei idea. Salvation is when you move through the world like a Jedi master.)

This is just a sampling of alternate visions of salvation, coming from religions around the world. A moment ago we heard Chad speak about yet another perspective, that of Wicca. To these, add alternate visions coming from decidedly non-religious sources. In 1859 we saw the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. Darwin’s thought in itself was complex and he saw room enough for God, but the main impression made on the public was a vision of reality that was stripped of anything supernatural. The purpose of life was survival of the species through procreation and also adaptation to a changing environment. Life is amazing in its diversity, but the struggle for existence is brutal and death is real and final. If salvation is anything, it is about living fully and richly in the here-and-now as well as leaving a generous legacy for future generations. The only immortality is an immortality of influence.

But this is not the only vision we get from science. Even science produces alternate visions. One of the ironic consequences of improved medical technology is a steady increase in reports of near-death experiences.

Modern resuscitation techniques have improved to the point where you have increasing numbers of people who’ve been to the brink of death and then come back to tell an amazing story of detachment from the body; seeing your body below you and “you” seem to be floating near the ceiling; feeling serenity, security, and warmth; feeling yourself moving quickly through a strange dark tunnel towards a light; encountering this light which is intelligent and compassionate and emphasizes that the purpose of life is love and learning. Study after study shows that these near-death experience elements are similar world-wide, irrespective of age, sex, ethnic origin, religion, or degree of religious belief. Studies also show that, following the experience, people go through a transformational process that encompasses life-changing insight, heightened intuition, and disappearance of the fear of death.

As for explanations of all this? Some scientists reduce these spiritual pyrotechnics to something purely physiological. Cerebral anoxia, for example. Other scientists, however, argue that these reductionistic explanations do an injustice to all the evidence as it holds together, and they go on to affirm ideas that were pitched out with Darwin. These scientists are saying that there really is more to existence than our physical, body-focused struggle. That the body is like a TV, and when it is well-functioning, it channels our soul’s signal. When it breaks down, it will appear to the outside onlooker that there is nothing left. Of course. But the soul signal that is the essence of you still persists. You persist but in a realm of existence too fine for physical senses to detect. Death is not final.

This, then, is how far we’ve traveled in five-hundred years, since Faustus Socinus. Liberal theology has transformed our ultimate sense of things from existential anxiety to existential safety. Furthermore, the singleness of Christendom has disappeared and has been replaced by a manyness of visions. Hinduism tells us that, yes, there’s such a thing as an afterlife but we actually don’t want that. We want to stop reincarnation and, through moksha, lose our unique selfhood and merge with Brahman. Buddhism and Taoism, on the other hand, have a more humanistic focus. Don’t wait for some afterlife to experience salvation. Here and now, learn how to enter into the life divine. And then there’s science which, for the most part, has emphasized that humanistic focus; but then it’s also been a surprising source of evidence for a view of reality that echoes more traditional teachings about the afterlife.

Five-hundred years, and this is where we are. And what I want to say this morning is that, as Unitarian Universalists, all this diversity can be an opportunity for us.

We can get beyond bewilderment. We can even get beyond the cynicism and apathy that multiple competing visions can lead to, a sense of “what’s the use?,” a sheer lack of caring about our spiritual welfare. What we can do instead, as Unitarian Universalists, is to actively engage intellectual curiosity. Take a balcony-view of the diversity—step back and look at it all from a larger perspective, and wonder about what we’re seeing.

And what we’ll discover is this. Names will vary (moksha, nirvana, wu-wei, Jesus) and ways will vary (the Four Yogas, the Noble Eightfold Path), but the constant and abiding theme is dual: (1) deliverance from a bad or difficult place and (2) resilience that enables greater aliveness. Deliverance and resilience. As the 23rd Psalm says, “Though I walk through the valley of death, You are with me. Your rod and staff, they protect me.” It’s in this psalm and it’s everywhere: salvation sustains hopefulness, salvation keeps us fluid and flowing no matter what life brings our way.

It’s even in football. It’s the great Vince Lombardi of the Green Bay Packers, who said, “It’s not whether you get knocked down; it’s whether you get up.”

Salvation is that: what keeps you getting up.

And we need THAT now more than ever. When you have hellishness and suffering up and down the scale (from the personal suffering we hold in our hearts to the collective suffering of a group or a city or a nation or a world or a polluted earth), there is no question about the need for salvation.

“It’s not whether you get knocked down; it’s whether you get up.”

As Unitarian Universalists, it’s our privilege to choose the words and ways that energize us to keep on getting up. For some of us, a word like God energizes us and brings us into a feeling of a larger life. For others of us, the word takes all the oxygen out of the room, oxygen that comes right back in when we speak instead of mindfulness meditation, or of the Goddess, or of being in nature. Religiously speaking, some of us are vegetarians; others of us are carnivores; and some are even omnivores. But we all know the sharpness of our spiritual hungers. We all know that.

So our responsibility to our spiritual wellbeing is to pay attention to what fills us up and feels good and to partake in that. And, as citizens of a shared Beloved Community, our responsibility is also to honor the differing hungers of others. To know that there’s enough soul food to go around. If a worship service serves up a plate of spiritual meat and you are a strict spiritual vegetarian, don’t fret. Every worship service is like a 10 course meal, serving up many plates, and the next plate coming up may be exactly what you’ve been hungering for.

The sermon is always a major plate in a service, and if it doesn’t satisfy your hunger one Sunday, it may do exactly that the following Sunday. Keep coming!

And now here is an offering of soul food for you to take in: a salvation story I’m going to end with.

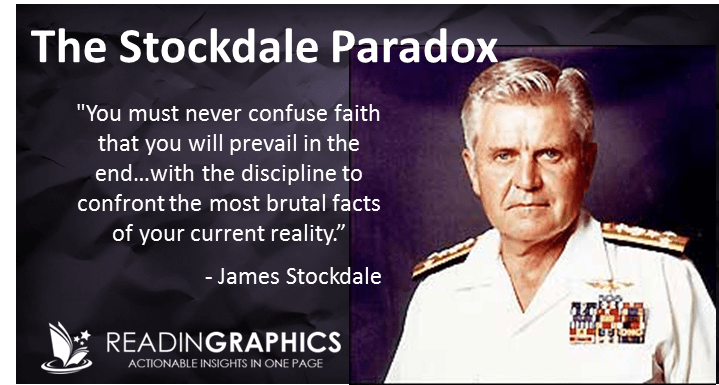

It’s about admiral Jim Stockdale, who was a United States aviator during the Vietnam War and was held in captivity for eight years.

Stockdale was tortured more than twenty times by his captors, and never had much reason to believe he would survive the prison camp and someday get to see his wife again. But he believed anyway.

The story comes out in Jim Collins’ book Good to Great. In the book, Collins and the admiral are taking a walk together, and the admiral says, “I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which, in retrospect, I would not trade.”

Says Collins, “I didn’t say anything for many minutes, and we continued the slow walk toward the faculty club, Stockdale limping and arc-swinging his stiff leg that had never fully recovered from repeated torture. Finally, after about a hundred meters of silence, I asked, “Who didn’t make it out?”

“Oh, that’s easy,” he said. “The optimists.”

“The optimists? I don’t understand,” I said, now completely confused, given what he’d said a hundred meters earlier.

“The optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say,‘ We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”

Another long pause, and more walking. Then he turned to me and said, “This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

That’s the story from admiral Jim Stockdale. Listen to the lesson. Salvation is both works and faith. Discipline to confront brutal facts head on; faith that you will prevail in the end.

Paradoxical wisdom that will save your life.

It is about salvation. Salvation keeps us fluid and flowing, no matter what. “It’s not whether you get knocked down; it’s whether you get up.”

This is what Faustus Socinus was saying five hundred years ago, the essence, the heart of it–and we need to keep saying it today.

Leave a comment