It was the Persian mystic and poet Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī who said, in the 13th century, “The task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.”

These words are at once hopeful and sobering. Love is a human potential. Love is at the center and, if we have the requisite wit and will to allow it, love expands until nothing is outside its circle. Preventing this, though, are the barriers people build. Harm to ourselves and harm to others happen because of the barriers we build.

Evolutionary biology helps to explain our readiness to build them. Predators, disease, and separation from the tribe were primary killers of our primeval ancestors. This brutal fact of ancient life is reflected in the structure of the brain. The oldest parts—the brainstem and limbic system—evolved over millions of years to contain an in-built “red alert” system, activating within a tenth of a second of detecting anything that looks threatening. Nature has wired our nervous systems so that bad news makes a way larger impression on us than good–a fact which politicians love to exploit with their negative messaging.

It’s called “negativity bias,” and side-by-side with it is yet another evolution-based bias: towards group polarization. If there’s a “we,” there will be a “they.” Experiments show that even if you have no clear reason to fear or hate someone from a different tribe–even if, all things considered, they come across neutrally–still, group psychology will make you suspicious towards them. If it’s a question of sharing resources, the polarization instinct leads us to favor our own. That is, unless getting less for ourselves is a guaranteed way of harming others we hate.

From evolutionary biology comes some answers, then. Barrier-building is a built-in instinct. To be human is to be vulnerable and survival requires us to be one step ahead of threats.

But why survive? What gives survival meaning?

Go back to Rumi: Love is the reason why. To love and to be loved.

The spiritual challenge we face, dear friends, is to bring disciplined nuance to moments when we feel threatened. Biology primes us to interpret mere discomfort or stress as full-blown danger. This priming includes a certain cognitive distortion called “all-or-nothing thinking” which kills all capacity for complexity and curiosity. We are primed in this way, in the encounter with anything strange, stressful, or disagreeable. But we are not slaves to biology. Spiritual growth is a path of increasing freedom. We learn how to step back from the moment of stress and create space in which we can get a healthier perspective. We learn to be more creative with the cards we’re dealt. We choose love over reactive fear. Conflict need not devolve into combat.

Biology gives us physical life, but spirituality makes life worth living.

In the year ahead, we’ll be exploring a form of spirituality called Transcendentalism, which resonates powerfully with what Rumi says about Love and barriers. Over time, truths can be lost, as much as anything can, and so one way of understanding Transcendentalism is that it represents an upsurge of forgotten truth about the soul force of Love within you and me. And so you have Henry David Thoreau in the 19th century in America, one of the classic Transcendentalists, saying “Only that day dawns to which we are awake.” Positive powers which shine like a sun are within us, ready to create a new day. But the sleeper must awaken. Confusion and delusion must give way to clarity.

Now, the textbook definition of Transcendentalism is that it was a 19th-century American philosophical and literary movement which produced some of our country’s first literary classics. Yes, and it is so much more! Transcendentalism is no mere relic of the past but a continuing inspiration for today. Agreed: the Transcendentalist writers are flowery in their writing, complex, a bit strange. But if you can get past that, what you discover are heroic people imagining new ways of living and new modes of being–people like Mary Moody Emerson (her nephew the better known Ralph Waldo Emerson), Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Sophia Peabody, Lydia Jackson Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and of course the aforementioned Henry David Thoreau. We’ll meet them through our congregational read Bright Circle, by Randall Fuller.

Next spring, in May, the series closes out with Mary Oliver, a poet so many of us cherish.

The sun that rises every morning symbolizes the sun within. If we awaken to it, the barriers Rumi says we build burn away.

So we begin.

Picture New England in the 1830s and 1840s—Boston and the surrounding area, especially Concord. People who would have regarded Ohio to be the rugged frontier.

What was happening back then?

For one thing, radical change. Before 1830, life was local. News and travel were sloooooow.

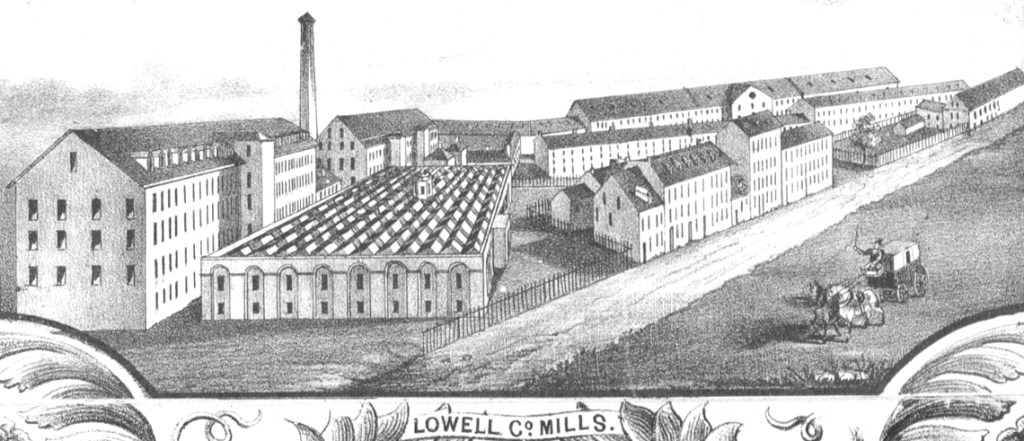

But then came the invention of the telegraph–instant messages across long distances. Then came the railroad, tracks crisscrossing the land, creating a new sense of national identity with breathtaking possibilities. It also brought new economic opportunities, allowing young people to leave home to find wage-earning jobs in cities or in the textile mills built along powerful rivers.

This process of industrialization, however, had winners and losers. It’s the old story of greed. Factory owners and merchants profited, workers suffered: long hours, low pay, unsafe working conditions. In 1824, women weavers in Pawtucket went on strike, and this is often cited as the first industrial strike in American history. In the 1830s, Lowell factory women organized strikes to protest wage cuts and 12-hour workdays.

Colliding with this was the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s. A massive wave of poor, Irish immigrants came to America. They took the lowest-paying, most dangerous jobs in construction, domestic service, and mills. Their willingness to do this, born out of desperation, drove down the pay for native-born workers and sparked ethnic and class tensions. Anti-Catholic hatred flared into hateful speech and worse: in 1834, an Protestant mob burned down the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

This was America in the 1830s and 1840s. Like all times, it was a mix of joy and woe woven so very finely together. Add to this economic meltdown. The Panic of 1837 brought bankruptcy everywhere. A Unitarian minister of the time had this to say: “We were in the midst of peace, apparent prosperity, and progress when, after extensive individual failures, the astounding truth burst upon us like a thunderbolt … that we were a nation of bankrupts, and a bankrupt nation.”

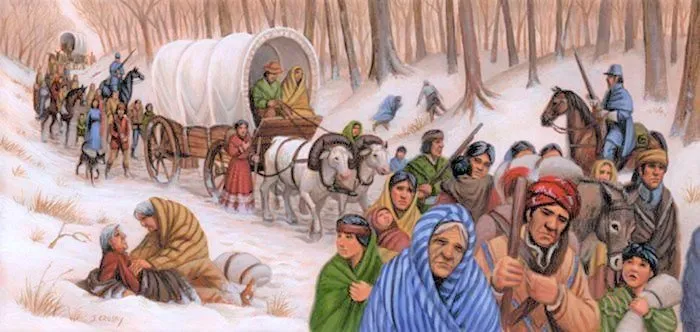

A moment ago I spoke of the railroad and breathtaking possibilities, despite the economy. Influential writers and politicians in the 1830s and 1840s believed in what they called America’s “manifest destiny” which was (quote) “to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” But this vision was laced with the poison of “all-or-nothing” thinking. Co-existence and cooperation with Native Americans who had already settled these lands for centuries was unthinkable. The result: the Trail of Tears, which saw the removal of Native Americans from their ancestral eastern lands to the west, traumatizing their cultures and leading to the sickness and death of thousands.

The Manifest Destiny mindset also led to an illegal war. In the 1840s, Mexico was struggling to maintain control of one of its territories, which happened to be called Texas. On April 25, 1846, Mexican troops ambushed U.S. soldiers north of the Rio Grande, land which Mexico said belonged to them. Several weeks later, President James K. Polk sang a different tune and told Congress that Mexican forces had attacked American troops on U.S. territory. He cried out, “American blood has been shed on American soil,” and Congress reacted with patriotic fervor. The House vote was 174–14 for war; the Senate vote was 40–2. Of the very few folks who voted against, one was a certain young, lanky politician from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln, who demanded, “Show me the spot!” Another critic, Robert Toombs, cried out, “This war is nondescript…. We charge the President with usurping the war-making power… with seizing a country [namely, Texas]… which had been for centuries, and was then in the possession of the Mexicans…. Let us put a check upon this lust of dominion.” That’s what Robert Toombs said. The war was illegal, a shameless land grab.

All this with slavery still entrenched. Slavery was the strangest bedfellow to the moral vision of the Declaration of Independence, which stated: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal: that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” These words had been originally aimed at England, experienced as the unenlightened oppressor. Yet England had abolished slavery in all its colonies in 1834. America, on the other hand, was seeking to expand it.

We declared equality, then denied it.

We dreamed liberty, but lived hypocrisy.

This was America in the Transcendentalists’ time. Sleepwalkers were everywhere. People were building barriers to Love left, right, and center. The facts of the time were brutal–so brutal that their force could have utterly extinguished any hope that life could be better than this, that people could be kinder than this, that America could return to faithfulness to its original Declaration of Independence values.

Hope back then could have died, just as hope might die today.

Dwell with me on this for a moment more, before we move on.

What I find especially fascinating is that the world of the Transcendentalists echoes our own. For one thing, technological shock then, technological shock now. Innovations like the Internet, smartphones, and social media have made hyperconnectivity a way of life with videos going viral and constant Tik-Tok and Instagram chatter. The “monkey mind” Buddhists speak of has gone planetary. Outrage artists from the Right and the Left vent their spleen and, if we’re plugged in, our biologically-based negativity bias and group polarization tendencies are constantly triggered–to the tune that we are in constant fight-or flight state and we are polarizing into extremes.

Who knows what AI is going to add to this mix.

As for the story of greed? Same old, same old. The rich continue to get richer, the poor continue to suffer, and the middle class is eroding fast. No more are there expectations of children doing better than their parents. Who are the new unemployed? College graduates. Unions are struggling, furthermore, and deregulation is the order of the day.

Yet another resonance is with the Irish immigrants. To use more current language, they were displaced refugees, forced to flee home because they were starving. Today, in 2025, over 123 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide, with 31 million fleeing across international borders. These people face immense challenges, including a lack of basic needs like food, water, shelter, and healthcare, and are vulnerable to human trafficking and violence. Jesus called such people “the least of these.” The Hebrew Bible, invoking the ancient duty of hospitality, spoke of “welcoming the stranger.” But in our land of the free and home of the brave, the refugee is met with an all-or-nothing message of “get out” together with inhumane treatment. The Biden administration might very well have fumbled the ball on immigration, but the current administration’s handling of it has gone the opposite extreme.

As for illegal wars, and anti-Constitutional practices. Of real wars, we could go on and on. The tragedy–the humanitarian crisis–happening in Gaza right now. Russia vs. Ukraine. But we can also speak of war in a more figurative sense. How about the war going on against the 1st Amendment and the right of free speech? Both the Left and now the Right need to answer for that. Both have practiced “freedom of expression for me, but not for thee.”

What seems truly new is the war against science. Power grabs by the current administration against universities, museums, late night TV. Retribution campaigns. Democracy in crisis.

Then there’s the war going on against yet another class of the most vulnerable among us, which are Trans folks.

We declare equality, then deny it.

We dream liberty, but live hypocrisy.

Hope, like a fragile candle flame, gutters in the chaotic winds and threatens to be blown out.

But the Transcendentalists, in times as rough as ours, did not give up hope. They still believed. They sought to imagine new ways of living and new modes of being. Elizabeth Palmer Peabody once described Transcendentalists as “People who have dared to say to one another … Why not begin to move the mountains of custom and convention?”

Why not? Why not?

How about we join them in that?

You and I, today?

The Transcendentalists believed that personal cruelty and social evil were symptoms of spiritual and moral sleepwalking. Albert Einstein, not a Transcendentalist but speaking their language, said, “Problems cannot be solved at the same level of awareness that created them.”

“Only that day dawns to which we are awake.”

Transcendentalists were very active in social reform moments, and we will explore this in detail in a later sermon. But an equally critical emphasis for them was the reform of personal character. Thoreau wrote, “Our limbs indeed have room enough but it is our souls that rust in a corner. Let us migrate interiorly without intermission, and pitch our tent each day nearer the western horizon.”

But how exactly do we do that—“migrate interiorly”? One answer is to commune with nature. The Transcendentalists believed that the interdependent web of all existence is not a machine of whirring, clicking parts. It has presence and spirit. If, as Thoreau says, our human souls are rusting in a corner, all we must do is bathe ourselves in the larger soul of Nature, and all the rust is removed. The barriers fall away and Love is revealed.

Other ways of “migrating interiorly,” for the Transcendentalists, included small group conversations, in which space was held for people to express their thoughts, tease them out, and make concrete that which only swirls around like smoke within. They engaged in disciplined conversation, journal writing, walking, and lots and lots of reading. You’ll never meet a bunch of mystics who read so much. Then there were the social experiments in enlightened living. Brook Farm comes to mind: a cooperative community consisting of teachers, students, and workers engaged in the labor of farming together with the labor of self-culture. Then there was Thoreau’s own social experiment of one: his time at Walden, lasting two years and two months.

It was all about moving the mountains of custom and convention.

Consider the mountains of custom and convention in our time. Extreme polarization and hate-filled culture. New York Times writer David Brooks speaks to this when he says, “History provides clear examples of how to halt the dark passion doom loop. It starts when a leader, or a group of people, who have every right to feel humiliated, who have every right to resort to the dark motivations, decide to interrupt the process. They simply refuse to be swallowed by the bitterness, and they work — laboriously over years or decades — to cultivate the bright passions in themselves — to be motivated by hope, care and some brighter vision of the good, and to show those passions to others, especially their enemies.

Vaclav Havel did this. Abraham Lincoln did this in his second Inaugural Address. Alfred Dreyfus did this after his false conviction and Viktor Frankl did this after the Holocaust. You may believe Jesus is the messiah or not, but what gives his life moral grandeur was his ability to meet hatred with love. These leaders displayed astounding forbearance. They did not seek payback and revenge.

Obviously, Martin Luther King Jr. comes to mind: “To our most bitter opponents we say: We shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We shall meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will, and we shall continue to love you. We cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws, because noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. Throw us in jail, and we shall still love you.”

Transcendentalism can mean many things. But for you and me today, it is an upsurge of forgotten truth about the Love that is within, which is at an instant available to us, potentially. Barriers to it have been built. Barriers that can get so bad you have to describe them as doom loops. But we can do better. The sleepwalker can awaken. Evil can be interrupted by the soul force of Love but only as we learn how to starve hate and cultivate the brighter passions instead.

Remember, spiritual growth is a path of increasing freedom. We develop a capacity for disciplined nuance as we face our fears and choose how to respond. We learn how to be more creative in our lives, with the cards we are dealt.

Even when the cards come at us with a knife.

The 1830s and 1840s are long gone. The classic Transcendentalists lived a long time ago. But we are going to see how they speak to us, intimately and profoundly, in the here and now, to help us declare equality and uphold it, to dream liberty and live it.

And–we can hold on to hope as much as they, despite the brutal facts.

If they could do it, we can too.

Leave a comment