A boy and his father were walking along a road when they came across a large stone. The boy said to his father, “Do you think if I use all my strength, I can move this rock?”

His father answered, “If you use all your strength, I am sure you can do it.”

The boy began to push the rock. Exerting himself as much as he could, he pushed and pushed. The rock did not move. Discouraged, he said to his father, “You were wrong, I can’t do it.”

The father placed his arm around the boy’s shoulder and said, “No, son, you didn’t use all your strength–you didn’t ask me to help.”

This story is about far more than the power of collective effort. It’s also about the power of cross-generational connection. Older and younger generations need each other. Developmentally, there is a need for children, youth, and young adults to feel that they are not alone in life, that they are protected, cherished, and guided. There is an equal need for adults and older folk to give back–to find meaning and purpose through mentoring younger folk.

Marc Freedman, author of How to Live Forever: The Enduring Power of Connecting, puts it like this: “What every child needs is at least one adult who is irrationally crazy about them. Studies have shown that kids who made it against the odds have had that kind of supportive village community with older people playing a key role. And it turns out that the parallel studies of happiness in later life show that older people need to be irrationally crazy about young people.

Older people who mentor and connect with the next generation are three times as likely to be happy as those who fail to do so.”

Cross-generational connection is just so important for the health and happiness of both younger and older people. It’s a kind of wealth. It’s the wealth of feeling good, less loneliness, lower levels of stress, less depression, improved child development, reduced crime rates, reduced risk of heart attacks, and lower overall mortality. Some folks call this kind of wealth “social capital.”

Add to the wealth of cross-generational connection inspiration. It’s inspiring and moving. For example, at the Newport Folk Festival in July 2022, 41 year-old singer Brandi Carlyle had an opportunity to sing “Both Sides Now” with her hero, the great Joni Mitchell, almost twice her age at 79 years old. It would be Joni Mitchell’s first full public concert in over 20 years. In a voice grown deep and raspy with age, she sang, (and you can sing along with me):

Rows and floes of angel hair

And ice cream castles in the air

And feather canyons everywhere

Looked at clouds that way

But now they only block the sun

They rain and they snow on everyone

So many things I would have done

But clouds got in my way

As one matures, says the song, one’s perspective changes. Youthful innocence gives way to a more nuanced understanding. With experiences of loss and uncertainty, something as simple as clouds turns complex. Love turns complex. Brandi Carlyle at 41 years is growing into this song’s wisdom and perhaps, like many folks in their 40s, is feeling quite overwhelmed. But she sings it with Joni Mitchell, now the wizened elder, who is in a place where she has more questions about life and love than answers, but she is undisturbed by that, she has made peace with that, she is still singing. The strength of her voice is reassuring. The experience is so emotionally powerful for Brandi that, on stage, during the performance, she starts weeping.

I myself wept while watching it. I’m watching it on You Tube and it took me immediately to a personal remembrance of the love and protection I felt with my grandparents, how I felt stronger when I was with them. Times when my life felt like a heavy rock, and it moved only because they were there to lend a hand.

On that Newport Folk Festival stage, back in 2022, I’d say that Brandi Carlyle and Joni Mitchell were irrationally crazy about each other. I was irrationally crazy about my grandparents and they felt the same for me.

I was rich.

But I had to give it up when my Dad, out of what he considered economic necessity, moved our nuclear family more than 2000 miles away. He was concerned about dollars, not social capital, not the wealth of cross-generational connection. Suddenly, at 13 years of age, I was without their strength.

So it was interesting how, a few years later, in the strange land of Texas I’d moved to, I found myself involved in a choral program that sought to bridge the age gap and bring younger people to nursing homes, to sing for them. Some of you might have been a part of similar kinds of initiatives. Each time we showed up, we wanted our voices to shine out to old people who seemed so very lonely and were so very grateful to be visited.

In retrospect, it was a band-aid solution to the terrible wound of age segregation. Speaking for myself, I left as lonely as I felt when I arrived. Our concerts did not make anyone irrationally crazy for me, nor I for anyone else. Gestures like this maybe felt good at the moment, but something deeper is needed to really tackle the problem.

The problem is clear when you look at the demographics. Age segregation in America turns out to be as entrenched as racial segregation. I call that entrenched. Furthermore, according to a 2018 survey conducted for the health insurer Cigna, the two loneliest groups in the country are younger people and older ones. These are the groups that suffer the worst. And so, says Unitarian Universalist author and psychologist Mary Pipher, “All over America we have young children hungry for ‘lap time’ and older children who need skills, nurturing, and moral instruction from their elders.”

It goes the other way too. Another Unitarian Universalist, minister and author Robert Fulghum, has famously said, “All I ever really needed to know I learned in kindergarten.” But this can only come from being with kindergartners, being among them, observing them. “Wisdom was not at the top of the graduate mountain, but there in the sandbox at nursery school,” says Fulghum. But how are older people going to learn these lessons and absorb this wisdom when they are always or most always elsewhere, stuck with people their own age?

Lack of consistent proximity of different generations, one to the other, has been built into American life. This is mainly a 20th century thing. As Marc Freedman reminds us, “In 19th century America, every major aspect of daily life was age integrated. Older and younger people worked side by side in the fields of an agrarian economy. Multigenerational households were the norm. Even those one-room schoolhouses of yore frequently found children and adults learning to read together under the same roof. Indeed, there was little awareness of age itself. People didn’t celebrate birthdays. Most would be hard-pressed even to recall how old they were.”

The turn from this–leading to today’s age-segregation–was not a matter of evil intentions, though. The key reasons and forces were mostly well-intentioned. Progress has also had its unfortunate and unforeseen side-effects.

First came compulsory education laws, created at the turn of the century, which essentially institutionalized childhood as a separate life stage.

Next came Social Security, established in 1935, which made retirement possible on a mass scale. Older adults were encouraged–or required–to leave the workforce, leading to retirement communities and age-restricted housing.

After this came consumer capitalism’s discovery of the teenager as a lucrative market segment. Pop music, fashion, and media targeted specific age cohorts, creating distinct generational identities. Mass media has only amplified this segmentation–making each generation feel like a separate tribe with its own style and worldview.

Then came a fourth factor: Preschools and daycare centers took over the job of childcare. Nursing homes and assisted living facilities took over the job of elder care. It used to all happen together, in the family. Now it was as if they were happening on entirely different planets.

And so:

Compulsory education for children.

Social Security and the invention of mass retirement.

The rise of the teenager.

The outsourcing of care–children here, elders there.

Four walls that now keep us apart.

Walls which sparked a revolution in worldview, which by now has settled into unquestioned common sense. Cross-generational connections went from “the way life is supposed to be” to “something nice to have, when possible, or when not too inconvenient.”

The personal is political. My dad moved my family from Canada to Texas and I lost my connection with my grandparents because, in today’s world, you go where the jobs are. Dollars matter. If the result is the break-up of multigenerational households or multigenerational connectivity, so be it. It’s just what people must do. It’s the way of the world.

Yet this age-segregated way the world is, in reducing regular opportunities for genuine intergenerational interaction, creates its own kind of poverty that dollars can’t solve. For one thing, it fuels prejudice and stereotypes. Younger people can see older people as “feeble or useless,” while older adults may view younger people as “careless and wasteful.”

Furthermore, opportunities for mutual learning are missed. Without meaningful contact, different age groups lose out on the wisdom, perspectives, and skills each generation has to offer. This creates a “self-inflicted wound” on society.

And then there’s the loneliness piece. Whatever your age, you have a stone in your life to move, and you don’t have enough strength all on your own to move it. Someone a different age, irrationally crazy about you, must lend a hand.

Only then will you have enough strength.

So when I learned about Providence Mount St. Vincent in Seattle, and their truly impactful solution to one dimension of the age-segregation problem, I felt so encouraged. The common sense in me that is the product of being an American at this time in history was simply blown away.

We saw a bit of this in today’s video. How Providence Mount St. Vincent is home to 400 residents and also home to 125 children who attend daycare in the building. How the Mount (as it’s nicknamed) has put together two age groups who essentially live in the moment, and when they can share together in that moment–the very young with the very old–what you have is a “present perfect” arrangement. Very old people, growing quieter and more remote through their aging, feeling expanded by being around the very young. Feeling effervescent. Enough to positively bubble and fizz and laugh and say

Fuzzy wuzzy was a bear

Fuzzy wuzzy had no hair

Providence Mount St. Vincent is one way of addressing the problem. Reversing the damage of age-segregation. Establishing consistent and meaningful proximity among older and younger.

Other examples of social innovation include Bill McKibben’s “Senior to Senior” project which is mobilizing “seniors”–older people–to register high school seniors to vote.

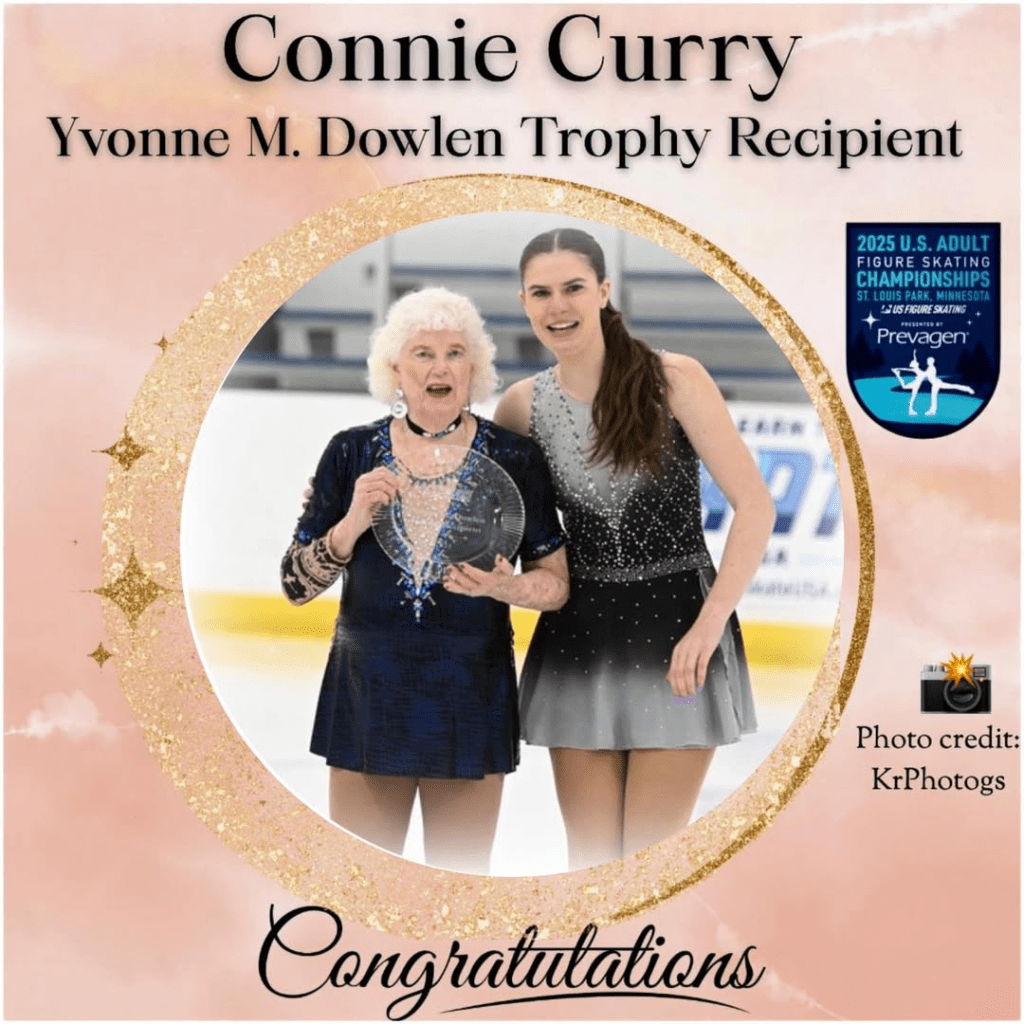

A personal favorite is something that happens at every Adult National Figure Skating Championships. The youngest competitor presents the oldest competitor with the Yvonne M. Dowlen Trophy. Here is 21-year-old Maggie Altmann honoring 86 year old Connie Curry at the most recent Championships.

Love for figure skating spans the generations, and therefore there is more love.

Then there’s the “Nuns to Nones” program which recognizes how today’s young social activists are often making things up as they go. They are not plugged into the richness of the wisdom and skills that, historically, religious communities like ours have made available to people. The sticking point is the rapid growth of disaffiliation from spiritual communities. People who see themselves as “spiritual but not religious” not feeling confident that they can learn anything really useful from religious folk.

That’s what it means to be a part of the N O N E S.

Enter the Nuns and the Nones. During a few organized exchanges between about 20 young activists and older Catholic sisters in 2016, the two groups recognized that they shared a similar impulse to integrate personal transformation with the lifelong work of pursuing social and ecological justice. Their conversations led to the formation of the first Nuns and Nones group, and this has sparked the creation of multiple other groups around the nation, in locations such as Boston; Chicago; Grand Rapids, Michigan; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Washington, DC; and the San Francisco Bay.

When generations come together, it’s as if time itself breathes easier–the past lending its wisdom, the future lending its fire.

Besides these project-based social innovations, certainly yet another category of needed innovation relates to basic policy. For example, current policy around national service initiatives has led to AmeriCorps for young people and AmeriCorps Seniors for older people and never the twain shall meet. But why? Why can’t national service become a multigenerational endeavor?

Because policy. Same goes for childcare and eldercare. Age-segregated licensing and accreditation rules make institutions like Providence Mount St. Vincent a rarity.

Change the policies. Also change the mindset that cross-generational connections are nice but optional. Become convinced that it’s a collective responsibility that people can no longer ignore, because the costs are becoming too expensive. A self-inflicted wound. Its own kind of terrible poverty.

What might it look like, here at West Shore, for the mindset to change? What kinds of innovative programs might we come up with, to be the change we wish to see? One of my ministry colleagues, the Rev. Peter Morales, has described church community as one of the very best places for breaking out of peer-age ghettos, and I think that he’s right. If we’re building a spiritual community that’s changing lives, we’ll be encouraging cross-generational connections.

Meaningful ones, not band-aids.

Every generation has its gift to give. Every generation has something to offer the others.

Whatever your age, you have a stone to move.

Strength to move it will come from someone older, or younger.

What every younger person needs is at least one elder who is irrationally crazy about them.

What every elder needs is at least one younger person who is irrationally crazy about them.

Life needs us to tap into all the strength we have.

Leave a comment