How many of you went to kindergarten? How many of you have children or grandchildren who go now?

Part of the story of my life is that I never went. I started Grade 1 when I was midway between four and five years old. Kindergarten to my parents seemed a distraction from the journey of my real education which was learning how to add and subtract, learning how to read and write, learning history.

The record shows that I struggled. My grade one report card says I daydreamed a lot. There was a voice still and small in me that would often lead me far away from the classroom. It would whisper that the tree I saw swaying right outside the window or the bird swooping past were more important than the worksheet on my desk with its problems to be solved. I found myself swaying with that tree or swooping with that bird until the teacher tapped me on the shoulder and interrupted wonder. I was ripped from awe and sent back to class. Back to work.

I never asked the question back then because I was too young to frame it. What was that voice still and small? And what had happened to it, as I progressed from grade to grade until gradually it receded in shyness and the only voice I recognized was the big voice of my teachers and parents and other authority figures? The big voice that eventually found a home within me, which Freud called the superego. Demanding voice. Anxious voice. Self-righteous, holier-than-thou voice.

Now, near my 60th year, I spend a lot of time wondering about the voice still and small. I spend a lot of time doing spiritual repair work, to become more open to hearing my inner wisdom voice which has been covered up by the years and grown shy. Learning to discern the voices coming to me from within: to sense which is the voice of my True Self, and which is the voice of ancestral pressure to perform, judgmentalism, tribal identity, fear, or even that of some social media algorithm.

Can you relate?

So can Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, a remarkable spiritual ancestor of Unitarian Universalists today. Though her name is too often left out of the story, she was not only present in the rooms where Transcendentalism emerged, she helped build those rooms. She helped give Transcendentalism form.

She did this, above all, through education–not only by asking the theoretical question of what it means to unfold a soul, but also by developing a clear method of doing that.

I want to explore a little of her story with you today not only because it’s inspiring and informative, but also because it centers a fundamental question of the spiritual life, one that matters deeply now: What does it mean to believe that every human being carries a truth-bearing voice still and small within them while also recognizing that there are also big voices, not true but loud and demanding, conveying delusion and division?

What does education–true spiritual education–demand of us now, in an age of social-media echo chambers, viral misinformation, and the seductive belief that “my truth” needs no testing, refining, or accountability?

To answer that, we begin at the beginning, with the mother who brought Elizabeth Palmer Peabody into the world: Eliza Palmer. She was formidable–strong-willed, principled, and unshakably confident in the power of women to shape the future of the young republic. She ran schools, taught classical history, and believed fiercely in education as a civilizing force.

Hers was a school of the old New England style. Strict discipline. Endless recitation. Memorization. The child was assumed to be unruly, incomplete, flawed, and needing to be corrected by big voices into virtue.

Eliza, above all, wanted her eldest daughter–her namesake, Elizabeth–to prove that women were the intellectual equals of men. The prejudice of the time against the female outraged her. But her outrage did not in any way soften the force of that prejudice. She felt her limitations painfully. “I long for means and power,” she once said to Elizabeth as a grown up, “but I wear petticoats and can never be Governor… nor alderman Judge or jury, senator or representative.” The best she could do would be to raise up a daughter who could excel in ways that she could only dream of.

Her intention behind nurturing Elizabeth into a genius was noble. And successful. When she was 18, Elizabeth took private Greek lessons from a recent Harvard graduate named Ralph Waldo Emerson, but when they concluded, he refused payment, explaining that it would be wrong for him to take money from someone who knew as much Greek as he did.

Yet the mother’s achievement had an unfortunate side-effect. It debilitated the daughter emotionally. Elizabeth was achingly lonely. A female uninterested in the outward show of proper dress and etiquette–proudly intellectual therefore an outcast. The pressure put upon her to succeed was hard to endure.

As a young woman, she wrote to the poet Wordsworth, sharing what she could not say at home. She said, “The education I received was wanting in power to connect together the heart and the intellect.” As a result, reality felt empty to her. Today, would we read that as PTSD? I don’t know. Later in her letter, Elizabeth expressed hope that Wordsworth would write something for children meant to encourage them to find their own path in life rather than worrying about satisfying the expectations of others.

The big voice of her mother hurt her deeply. But she inherited her mother’s strength. Strength enough to question the manner of her own education which, admittedly, brought her into her brilliance. But where was the tenderness? Where was attentiveness to the soft voice of her True Self within, to the interests stirring in her own True Heart and not someone else’s?

Her personal story, pain-filled, would be a prime mover in her life, in her search for a better form of education,Transcendentalist-style.

Besides her mother, another formative influence (this one purely positive) was William Ellery Channing, whom we today know as the father of American Unitarianism.

Short, angular, elegant, his Federal Street Church congregants loved his sermons and loved his bold ideas. One of these key ideas was that each person is born with a divine spark within–not something to imposed from without, but already there, needing to be acknowledged and drawn forth. Channing rejected the old Calvinist doctrine of innate sinfulness. He proclaimed instead that every person is born not fallen but rising–a soul unfolding in divine possibility.

Children included!

While Elizabeth had encountered Channing several times as a child and teenager, it was in her early 20s when the relationship between the two solidified into his mentorship of her. He recognized the genius she was. She recognized how his ideas were showing a new way forward. He wasn’t a source of a clear educational methodology, but rather a vision yet to be grounded in practice: a vision of the child as inherently capable and the task of education not to repress but to draw forth.

Not just children, however. The learning process is lifelong. He called it “self-culture,” saying, “The ground of a man’s culture lies in his nature, not in his calling. His powers are to be unfolded on account of their inherent dignity, not their outward direction.” In other words, there is inner and there is outer. The latter must honor and serve the former.

As part of his loving mentorship, Channing introduced Elizabeth to the French educational theorist Joseph de Gérando. He urged her to translate his book Self-Education into English so that it could be appreciated by a wider audience. Here she found another genial soul, and she thrilled to read him say such things as the following: “The fundamental truth which solves all the problems that agitate the human heart, and trouble the growing reason … is this:–the life of man is in reality but one continued education, the end of which is, to make himself perfect.” (Read perfect as whole, not flawless.)

Mentors like Channing and de Gerando encouraged her to be innovative in her own right, but in another sense they were simply helping her fulfill an insight that struck her years earlier, when she was just 13 years old. The story goes that one day she marched into the family parlor and announced her opinion that Jesus was not God himself, but human, and that it was the duty of all believers to improve themselves so as to attain wisdom and goodness equal to his. She intuited this all on her own. Ralph Waldo Emerson would say as much in his 1838 Divinity School Address, preached to an audience of Harvard grown-ups, most of whom immediately declared him heretical.

But 13 year old Elizabeth Palmer Peabody beat him to the punch!

At around the same time that she was translating de Gerando’s work into English and thrilling to the vision of the voice still and small within, she started something she called her “historical conferences.” Around eight hours a day, twice a week, she gathered a group of young women for the purpose of discussing ancient Greek and German texts. Under her tutelage, their conversations would be the means whereby the inner wisdom voice would be drawn out. She needed the money made from this venture. But it was also an opportunity to take educational theory and make it practical. There was something utterly unique and powerful about small group conversation–as opposed to soliloquies in the privacy of one’s own mind. As historian Randall Fuller says, “The best way to plumb the depths of the self, Elizabeth thought somewhat paradoxically, was through interaction with others.”

With this, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody’s path would intersect with one of the greatest Transcendentalist conversationalists of them all: Amos Bronson Alcott.

Bronson Alcott was visionary. A brilliant talker. Unconventional.

Also exasperating and profoundly impractical.

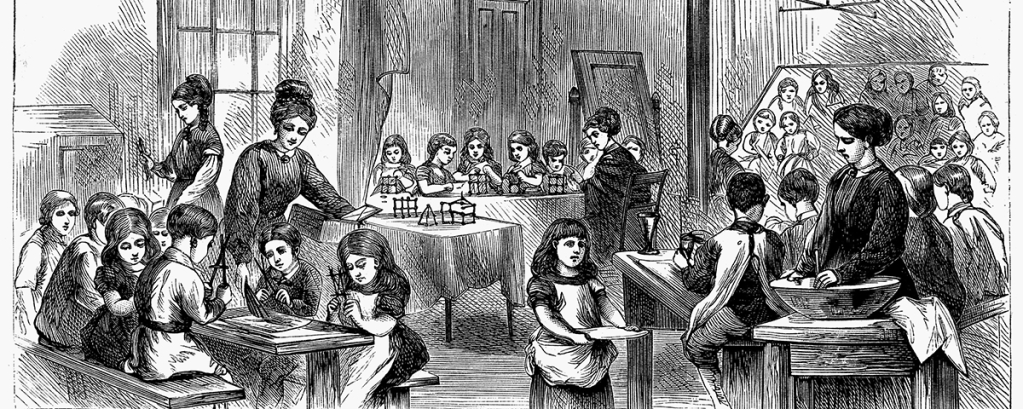

In 1834, he founded the Temple School in Boston. No punishments. No drills. No rote recitation. Children sat in conversation circles. They were invited to reflect, to imagine, to reason for themselves. The school ran on spiritual trust.

Alcott treated the child as a philosopher and mystic. In one corner of the classroom sat a bust of Plato. In another, a bust of Socrates. In a third, Sir Walter Scott. In a fourth, Shakespeare. As if to invite them into the education Bronson Alcott was giving the children–souls in active formation.

Elizabeth served as his assistant and, importantly, his recorder. She wrote down the lessons. She shaped the transcripts. She tried to make sense of the method, the spirit, the aspiration. Her efforts led to the publication, in 1835, of Record of a School, in which she communicated the astonishing things that Alcott was accomplishing. Children blossoming, growing confident, articulate.

But it also reflected growing concern about some aspects of Alcott’s approach which, in her mind, weren’t working. For one thing, the conversational topics could be developmentally inappropriate and cause more confusion than clarity. Something else were times when Alcott’s conversations with the children seemed manipulative, and he would lead them to answers he’d already decided were the correct ones. This last tendency, in particular, seemed in direct conflict with Alcott’s stated faith that education should draw out, not press in.

Above all, there was Alcott’s profound impracticality. She valued Alcott’s vision. But his implementation was too off-the-cuff, too improvisational, and not reliably reproducible. The vision needed better structure, better methodology.

The Temple School eventually collapsed. But Elizabeth carried forward the lessons.

Not long after, she had yet another encounter with a Transcendentalist whose utter oddness proved a need to test the inner voices, to discern which is of the True Self and which may be big and loud but ultimately delusional.

I am speaking of the poet Jones Very, a brilliant but fragile man who became convinced that he was divinely inspired in a literal sense. He claimed the Holy Spirit had descended into him; he believed his every thought sacred truth.

Elizabeth tells a story of one frightening encounter. “One morning I answered a ring at the door, and Mr. Very walked in. He looked much flushed and his eyes very brilliant and unwinking. It struck me at once that there was something unnatural and dangerous in his air. As soon as we were within the parlor door he laid his hand on my head and said ‘I come to baptize you with the Holy Ghost and the fire’ and then he prayed. I cannot remember his words … as I stood under his hand, I trembled to the centre. I felt he was beside himself and I was alone in the lower story of our house.” Elizabeth somehow maintained her calm, stayed silent, until Very asked her if she felt changed. No, she replied. He said, “But you will …. I am the Second Coming.” Eventually, thankfully, he left.

The larger lesson in all of this for Elizabeth was what happens when a loud inner voice is taken as infallible simply because it is loud.

Years later, in 1858, she wrote an essay called “Egotheism, the Atheism of Today.” In it she spoke of people who treat their own ideas as the whole of truth–as she put it, they “deify their own conceptions, that is, they say that their conception of God is all that men can ever know of God.” They also become detached from others and the larger social world. Remember her “historical conferences” and her conviction that the best way to plumb the depths of the self was through interaction with others? Without that interaction–without the tempering effect of discussion and debate on our ideas–the result can’t be good.

To ignore the self’s limitations is to risk insanity, disgrace, or censure. Jones Very was not the only one she had in mind, though. She was also thinking of Alcott. And–gently, lovingly–even Emerson.

The voice still and small is real. But there are other voices coming from within the self, loud, which elbow everything else out of the way. How do you create room for that shy, quiet, voice of the True Self to step forth? To protect it from the shaming that the loud voices give it, to banish it back into silence?

Her work of championing the kindergarten and its way of doing just this is a gift she gave America that keeps on giving. It’s one of the enduring embodiments of Transcendentalism, beyond famous speeches and sermons and books.

In 1859, Elizabeth became acquainted with Margarethe Schurz, one of the students of Friedrich Froebel, the German educator who created the first kindergarten. It was a completely new word he coined–”kindergarten”–which meant “children’s garden.” A garden nurturing children’s development through play, creativity, and hands-on activities. Listening to Margarethe Schurze, a picture formed in Elizabeth’s head, perhaps this one: of a room–bright, warm, and orderly. Morning sunlight pouring through tall windows. No rows of desks. No raised teacher’s platform. Instead: a circle of small wooden chairs. The circle was intentional. It meant: every child belongs. Every child is visible. Every child is part of the whole.

Along one wall, low shelves that held what Froebel called Gifts: Smooth wooden spheres and cubes. Colored papers for weaving. Natural objects gathered from outside–stones, pinecones, leaves. Not toys to distract the mind but materials chosen to awaken attention and wonder.

There were no textbooks. No drills. No recitations. Instead, song.The children sang together as they began the day, their voices light and clear. Not performance. Belonging.

One child arranged wooden cubes into a tower to learn balance and patience. Another wove threads into a star pattern, learning symmetry, beauty, harmony without yet naming those things. Some children moved in a circle, singing as they walked, learning rhythm and relationship through the body.

Elizabeth, dreaming this day dream as she listened to the student of Friedrich Froebel, saw herself moving among them: not policing, not correcting, not dominating, but attending. Kneeling to meet the children at their level. Asking: “What do you notice?” “Where does your idea want to go next?”

Elizabeth Peabody devoted the rest of her life to bringing this to America. She trained teachers. She wrote manuals. She gave public lectures. And opened the first English-speaking kindergarten in this country.

We are heirs of this–in every preschool, every circle-time, every classroom where curiosity leads and the child’s dignity is honored. Including our Sunday school classes here at West Shore.

This was not the severity of her mother’s schoolroom. It was not the unstructured idealism of Bronson Alcott. It was not the isolated, self-confirming intensity she had seen consume Jones Very.

Listening to Margarethe Schurz, everything she had learned came together. The inner spark is real. The voice still and small must be invited forth, without shame or pressure, with creativity and joy.

Which brings us to our present historical moment. Now we close the loop and come back to the fundamental question of the spiritual life which I raised at the start of this sermon: What does it mean to believe that every human being carries a truth-bearing voice still and small within them while also recognizing that there are also big voices, not true but loud and demanding, conveying delusion and division?

Today, like Elizabeth, like the Transcendentalists in general, we speak of: “finding your voice,” “trusting your truth,” “listening to your inner wisdom.” But we live in a time when our attention is manipulated by algorithms designed to be addictive. We live in a time when our beliefs are shaped by echo chambers. All times are times when certainties are reinforced by tribal identity. All times are times when our inner voices are easily confused with our anxieties, resentments, and fears.

For example: a parent reads on the neighborhood message board that someone “suspicious” is walking on their street. The post is vague. But the replies, dozens of them, come fast: Lock your doors. Be careful. Don’t let your children outside.

The fearful energy is contagious. By evening, the entire block feels under siege. The next day, the “suspicious person” is identified: A young woman going door-to-door delivering political flyers. Nothing happened. But in that moment, fear felt like truth. Fear mimics intuition. It feels like insight. But it does not always come from the inner spark. Sometimes it is just the nervous system ringing an alarm without evidence.

If education only calls forth without cultivating discernment, we end up not with awakened souls but with loud inner voices that become only louder. Peabody saw this danger clearly long before the internet. She believed the spark within us is real but inner voices must be tested, shaped, and refined in community. The point of spiritual community is not to give us our truth but to help us discern it.

The voice still and small is always there, never gone. Only waiting. Our work–as Peabody’s work was–is to make a clearing for it, and to make that clearing together.

May we learn to listen for the quiet truth beneath the loud voices.

May we be students of the soul, in community.

May we sing together–of the voice still and small.

Leave a comment