There’s a classic Unitarian Universalist way of talking about nonconformity and resistance to social pressure.

You probably know where I’m going.

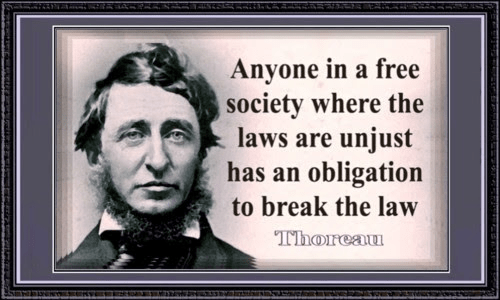

We lift up Henry David Thoreau–living at Walden Pond, refusing to pay his poll tax because he would not support a government that upheld slavery and waged war on Mexico. We remember his jail cell, his stubborn conscience, his essay “Civil Disobedience.” We name Thoreau as one of our patron saints of principled resistance.

And it’s a good story. It deserves to be told.

But it’s not the only story.

This morning I want to lift up a quieter kind of nonconformity–no jail cells, no fiery manifestos, no heroic arrest. Instead: a sickroom, paint and canvas, a riding horse, a private journal, and a woman trying to hold onto her soul when nearly every pressure around her is pushing her to become someone else.

Her name is Sophia Peabody.

And through her, I want to explore a larger question that feels incredibly urgent in our time: When is nonconformity truly valid and life-giving, and when is it actually unhealthy, ego-driven, or even destructive?

Because in our time, “resistance” is fashionable.

“Being different” is a brand. Outrage is a lifestyle. And nonconformity is not always what it seems.

Sophia Peabody lived in the same orbit as the Transcendentalists: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, and so on. The Transcendentalists were united in a restless dissatisfaction with the status quo of New England life. They were tired of what one historian calls “frosty New England”: a world of stiff formalities, chilly suppression of feeling, and religion that felt like gray doctrine rather than living experience.

Sophia once wrote about “the reserve and coldness in intercourse. It is a dead blank in the eye of the soul I think.”

The Transcendentalists wanted more aliveness. They wanted the soul to breathe.

We usually tell this story through the loud ones: Thoreau, Emerson, radical public lectures, civil disobedience, communal experiments. But Sophia had her own Transcendentalist motto. She wrote: “A free & aspiring mind is the only reality worth seeking; for such a mind will find what it seeks–even Freedom & Excellence Infinite.”

That sentence alone could be the sermon.

A free and aspiring mind is the only reality worth seeking.

Before I go deeper into Sophia’s life, though, I want to suggest a framework for thinking about the issue of nonconformity.

Nonconformity is not one thing but two, and whether it is healthy depends entirely on what part of the self is generating it. On the one hand, there is what we could call soul-rooted nonconformity. On the other, there is “thymotic nonconformity.”

Thymos is an ancient Greek word naming the part of us that craves honor, recognition, and something to be righteously angry about.

Let’s take them one at a time.

Healthy nonconformity shows up whenever a person needs to protect or advance the integrity of their authentic self against pressures that would distort or erase it. By “authentic self,” I mean at least three things woven together–see where you recognize yourself in these:

First is the givens of your being. The parts of you that simply are:

- your temperament, introvert or extrovert

- your basic interests and enjoyments

- your sexual orientation

- the color of your skin

- your age, your body, your neurotype

- your cultural and ethnic background

These are facts of your existence. Trying to mold them into someone else’s image–or feeling the heavy hands of others upon you, forcing you to be different–only leads to injury.

Besides these facts of your existence, there’s your soul’s developmental path. You are, to use old language, a child of God–or in more secular language, a psyche in process, on a journey toward greater wholeness. You are at a particular level of psychological and spiritual development. That level comes with gifts and limitations. You have a right to grow at a healthy pace, to outgrow old patterns when it’s time, and not to pretend to be more mature–or less–than you truly are.

Finally, there’s your moral and intuitive core–that deep inner sense that says: “This is true; this is not.” “This is right; this is wrong.” “This is my path; that is not my path.” These are not just opinions. They are deep recognitions that grow out of the encounter between your soul and reality.

Your authentic self is composed of these three things, then: the givens of your being, your developmental stage, and your moral and intuitive core. Now my point: When social pressures threaten these domains, resistance is not only valid but necessary. Healthy nonconformity says: “I cannot pretend to be who I am not.” “I cannot shrink my soul to fit your comfort.” “I cannot betray what is clear to me.”

This is the kind of nonconformity we see in Thoreau’s refusal to support slavery and unjust war, or the civil rights movement and Black Lives Matter, or LGBTQ+ people telling the truth about who they are, or a person leaving a toxic religious community after years of trying to stay loyal.

This is nonconformity that arises from the soul.

But remember, there is another kind to consider. There can be nonconformity arising not from the soul, but from the inner thymos–that part of the psyche that desires recognition and honor, that loves to feel outraged and fired up, that wants to stand out and feel important.

This kind of nonconformity is not about truth. It’s about intensity. It looks like:

- protesting simply to protest

- standing apart just to feel unique

- creating outrage to feel powerful

- opposing authority simply because it is authority

- romanticizing the worst ideas of history because it shocks people (like Nick Fuentes and the Groypers on the Right)

- boiling all of reality down to a simplistic oppressed/privileged scorecard, where nuance is dismissed and rage feels cleaner than complexity (like too many folks on the Left)

This is all reactive rather than responsive, egoic rather than authentic, identity-hungry rather than integrity-driven.

And here’s one of the most dangerous things about this thymotic nonconformity: It often feels like authenticity. It feels “real” because it is intense. If it makes me feel big, important, defiant, or righteous, well then, it must be my truth, right?

Not necessarily.

Here is the simple diagnostic question to pose, to tell the difference: Does my nonconformity protect who I truly am? That’s soul.

Or, does it just help me feel big, special, or perpetually offended? That’s thymos.

Healthy nonconformity, I’ll add, is almost always accompanied by humility. Unhealthy nonconformity by self-importance.

The deeper spiritual task is to learn which is speaking in us.

Into this framework, now, we bring Sophia Peabody. She did not write “Civil Disobedience.” She did not go to jail. Her resistance was quieter. More interior. More aesthetic. More relational. And yet, I would argue, it was profoundly healthy.

Let’s look at some of the main pressures she faced, and how she resisted them in ways that preserved her soul.

Sophia was born into a world where life for a respectable New England woman was fairly well laid out. Behave properly. Marry suitably. Keep your ambitions modest. Keep your feelings subdued. Remember how she described frosty New England–full of “reserve and coldness… a dead blank in the eye of the soul.”

And yet from an early age, Sophia had a fierce aesthetic and spiritual sensitivity. She lost herself in beauty. She once wrote: “I always seem to myself to be blended with anything that excites my admiration & I am lost in what I gaze upon.”

One night, awakened by a thunderstorm, she suddenly thought, “God is here.” She felt herself “in the arms of Infinite love.” Her spirit poured out into nature.

Later, walking in the woods with pencil and sketchbook in hand, watching leaves turn russet and orange, she wrote: “I held my breath to hear the breathing of the spirit around me… Oh I know I shall be better than I have been for years in this solitude.”

This was not a hobby. This was her religion.

Throughout her life, Sophia believed that the world was presided over by a benevolent spirit who guided the ultimate progress of the universe. Natural beauty was one of the main ways she experienced that spirit. To gaze on wildflowers, or a sculpture, or a tropical sky was to glimpse the creative power of God.

In a world that treated religion as abstract doctrine and women as decorative, Sophia’s conviction that art and beauty were doorways to the divine was a quiet but radical nonconformity.

She refused to live a flattened, purely respectable life. She refused to let her world be colorless. She would have an inspired life, or none at all.

In Sophia’s time, serious painting–especially oil painting–was considered a man’s domain.

Genteel ladies might draw flowers in watercolor. But the “public practice of any art and staring in men’s faces,” as one authority put it, was “very indelicate in a female.”

Oil painting was “masculine,” a muscular wrestling with a difficult medium. And to be an ambitious female artist, to exhibit work publicly, was often likened to a kind of social or moral immodesty.

Against this backdrop, Sophia studied with some of the most respected artists of her time. She became one of a very small number of women in the United States who actually made a living as a painter.

Her canvases, often copies of European landscapes, were prized by middle-class Bostonians who rarely saw the originals. An important artist, Washington Allston, respected her talent enough to tell her to stop copying other painters altogether and instead copy nature itself.

Every brushstroke for her was an act of nonconformity. Not in the sense of picketing outside institutions or writing manifestos against patriarchy, but simply in refusing to obey the script that said “ambitious art is not for you.”

This is soul-rooted nonconformity: “I cannot pretend I am not an artist, simply because it would make you more comfortable.”

Yet we must not oversimplify the pressures Sophia faced. It wasn’t purely patriarchy. Sophia’s eldest sister, Elizabeth, from day one had been marked by her mother Eliza as a kind of second coming of female empowerment. Elizabeth was to be the powerful woman that her mother could only dream of being, and that power would take the form of a serious, brilliant intellect.

So when the mother directed Elizabeth to take charge of Sophia’s education, Elizabeth sought to extend what she herself had experienced. Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Theological treatises. Philosophical histories. A stern exhortation to “unremitted industry.” If it was good for boys’ minds, it was good for girls’ minds.

On one level, this was feminist: mind has no sex.

But alongside the gift was a pressure. Elizabeth was determined that Sophia’s mind should develop along a specific, rigorous, rational, theological line–Elizabeth’s line. And Sophia was grateful. She was a diligent pupil. She loved her sister.

Nevertheless, resentment simmered. She did not like being told what to do. Above all, her heart was drawn less to abstract philosophy and more to poetry, art, and sensual experience. Elizabeth’s severe logical style went against the grain of who Sophia was. Her commonplace book shows this tension. She copied Wordsworth and Coleridge, yes–but also Keats, for whom “the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration.” She copied Byron, whom Elizabeth denounced as immoral.

Elizabeth criticized Sophia’s writing as too ornamental, her French turns of phrase as “slang.” She dismissed Sophia’s rapturous descriptions with a tart line: “Sentiments about beauty do not constitute religion.”

Sophia quietly, stubbornly, disagreed. For her, beauty was religion.

Here again, we see soul-rooted nonconformity. Not a dramatic break, but an inner refusal to abandon her own path.

Sophia once wrote that she sometimes imagined she could only be truly free if Elizabeth were dead. Gratitude and suffocation lived side by side. How many of us know that feeling? Gratitude to a parent, mentor, or elder. But also a deep sense that to follow their script exactly would mean betraying our own soul.

To say no–even inwardly–can be a form of nonconformity. A necessary one.

And there was even more pressure Sophia endured–this time from her mother. Her mother, Eliza, was exhausted by the time Sophia came into the world–worn down by poverty, her husband’s failures, her own chronic pain treated with opium.

She treated Sophia differently from her other daughters. She “firmly resisted all coercion” in her upbringing, she said. When as a baby Sophia “shrieked,” Eliza soothed, comforted, melted her heart. On the surface, this sounds gentle. But over time, Eliza encouraged Sophia to identify as an invalid. Meals were brought to her room. The household tiptoed around her. They even petitioned the Massachusetts governor on the Fourth of July to redirect cannon fire away from the park so the noise wouldn’t disturb her.

Eliza insisted that Sophia’s “sensitive nerves” would only worsen each year. The “tenderest and loveliest mother in the world,” as Sophia later called her, also kept her daughter close by defining her as too fragile for the wider world.

But when Sophia went to visit her Aunt Mary in Vermont, something remarkable happened: she rode horses, climbed mountains, and her headaches disappeared. Her mother’s reaction? Not relief, but utter panic! Letters flew: You don’t have enough clothes. You’re inconveniencing your aunt. You’re too sick to be useful there; if you were well enough, you should be home helping your brothers. I miss your cheerful voice. Come home. Live upon the past.

Sophia was not yet twenty. She had no desire to “live upon the past.”

Her longing to escape the sickroom–to breathe, to ride, to climb, to see–was a profound act of nonconformity against a family system that needed her to remain small, fragile, and close. And we might say: if her mother’s dynamic wasn’t full-blown Munchausen by proxy, it certainly rhymed with it.

Sophia’s soul knew: I am more than my illness.

Her resistance here was not loud. But it was real. Saying “yes” to the mountain and “no” to the sickroom was an act of spiritual courage.

Speaking of illness and its cure, we must also consider the role of the medical establishment in Sophia’s time. As a baby, Sophia had been given teething powders laced with calomel–mercurous chloride–because that was standard medical practice. Later she was given opium, henbane, arsenic, and subjected to bloodletting and leeches. “Heroic medicine,” it was called.

We know now that mercury is highly toxic. We know what opium dependence can do. We can see the medical establishment of her time as a system that harmed her while claiming to heal.

Sophia could not.

She suffered excruciating headaches, delirium, terrifying dreams. She called the pain “the demon in my head.” It is heartbreaking to learn this.

But even here, she reached for meaning. She sometimes saw her suffering as a form of spiritual refinement, a way God taught her the art of renunciation. She wrote that “Sickness and Pain are some of the highest ministers of God’s inexpressible love.”

We might want to argue with that theology. We might want to say, “No, sickness is not a gift.” But there is something in her determination not to waste her suffering that reflects a kind of inner freedom.

And her story also reminds us of this: There are pressures we conform to today that we cannot yet see clearly. Future generations will look back at some of our “standard practices”—cultural, medical, technological, economic—and say, “How could they not know?”

Sophia’s story invites humility. We resist what we can see, but we also pray for insight into what we cannot yet name.

At one point, a doctor recommended a cure: travel to a warmer climate. So Sophia went to Cuba for eighteen months. Almost immediately, her health improved.

Are you seeing the pattern there? Whenever she stepped even a little bit into a life that fit her soul (mountains, horses, warm air, art), her symptoms eased. When she returned to roles that shrank her, they worsened.

Her journal from that time–the Cuba Journal–is remarkable. It’s filled with vivid descriptions of tropical skies, lush vegetation, birds, local customs, early-morning rides on her horse, Guajamon.

She describes riding past “a dark impenetrable wood” under a crescent moon, clouds “deep saffron” holding the last light of the sun. She compares the atmosphere to a soft shawl around her shoulders. She bites into a sun-warmed guava and jokes that if there had been an Adam nearby, she would have said, “Take thou & eat likewise.”

The journal is part travelogue, part spiritual autobiography, part coming-of-age story. It is also one of the earliest pieces of Transcendentalist nature writing we have, preceding Emerson’s “Nature” by two years and Thoreau’s Walden by more than a decade. For a woman, in that time, to write that way, to attend so seriously to her own perceptions, to claim that her experience of beauty was spiritually authoritative–this was nonconformity.

To travel away from her mother, away from frosty New England, into a landscape filled with color and scent and sensuality–this too was nonconformity.

It was, in the deepest sense, obedience to her own soul.

And then there was marriage.

From a young age, Sophia did not intend to marry. It seemed like a kind of death: a loss of freedom, a mortal danger in childbirth, the end of possibility. She once dreamed of the sky filled with cloud-coffins when a friend married. The message was clear.

And yet, when she accepted the proposal of a shy, struggling writer named Nathaniel Hawthorne, she did so with a very specific nonconformist vision. She believed they could create a marriage that was a partnership of equals, a creative collaboration, a life shaped like a work of art. She imagined a house where he would have his study and she her studio, one above the other. In the mornings, each would go to their work, “in the hands of their Muses.” In the afternoons they would come together and exchange thoughts that had visited them from “the Unknown deep.” She wrote of the felicity of hearing him, telling him her own discoveries, showing him her inscriptions with pencil and sculpting tool.

They called their new home Eden. “We are Adam and Eve,” she wrote to her mother–only this time, Eve was not a subordinate helper but a full co-creator.

Was their marriage as idyllic as that vision? Of course not. Real marriages never are. Nathaniel’s economic instability and moods were real. Patriarchy did not magically vanish at the threshold of their home. But the vision itself was nonconformist: a marriage that resisted the script of female disappearance, mother’s control, and resigned domesticity. A marriage that insisted both partners had the right to create. This, too, was soul-rooted nonconformity.

Let’s now bring this all home. What do you and I do with all of this?

We live in a time that celebrates nonconformity on the surface and yet demands conformity in countless hidden ways. Some of us feel overt pressures: to hide our identity, to mute our gifts, to remain loyal to groups or leaders who no longer deserve our loyalty, to keep family harmony at the cost of our own truth, to pretend to be younger, stronger, more “together” than we really are.

Others of us are caught in more thymotic temptations: enjoying our own outrage a little too much, clinging to a contrarian identity simply because it makes us feel sharper or edgier, mistaking intensity for authenticity, defining ourselves by what we are against more than what we are for.

Sophia’s life, and the earlier framework I laid out for thinking about nonconformity, offer us a spiritual practice of discernment. When you feel the urge to resist, to defy, to stand apart, to say “no,” you might ask: What part of me is speaking right now? Is this my soul speaking–protecting my authentic being, my growth, my moral clarity? Or is this my inner thymos–my craving to feel important, outraged, or special?

Does this act of resistance help me become more whole, or just more dramatic? Is there humility in it, or only self-importance?

If I imagine someone I deeply trust and respect watching me, would I feel more grounded–or slightly embarrassed?

Healthy nonconformity may look quiet from the outside. It might simply be: Choosing a profession that actually fits who you are, instead of the one that flatters your family. Choosing not to laugh at a cruel joke. Ending a conversation when it becomes dehumanizing. Coming out as who you truly are. Starting therapy even though your family says you should just “tough it out.” Walking into the metaphorical mountain air when everyone else insists you are too fragile to leave the sickroom.

Unhealthy nonconformity may look dramatic from the outside–big gestures, big statements, big outrage–and yet leave you emptier than before.

Our call, as people of faith and conscience, is not to be nonconformist for its own sake. Our call is to be faithful–to the truth of who we are, to the demands of justice, to the whisper of the Spirit, to the next right step in our growth.

Sometimes that will make us stand out. Sometimes it will make us blend in.

The question is never simply: Am I conforming or resisting?

The deeper question is: Am I shrinking or am I becoming more real?

Remember what Sophia Peabody once wrote: “A free & aspiring mind is the only reality worth seeking; for such a mind will find what it seeks—even Freedom & Excellence Infinite.”

A free and aspiring mind.

Not a noisy mind.

Not an outraged mind.

Not an egoically special mind.

But a mind that is free enough to follow truth, and aspiring enough to keep growing.

So I leave you with these questions: Where in your life are you being asked to conform in ways that would erase your authentic self? Where are you being urged to rebel in ways that don’t actually deepen you, but only inflame you? Where might you, like Sophia, need to pick up your sketchbook, or your journal, or your suitcase, or your courage–and step out of the sickroom?

May we have the courage to say no when no is holy.

May we have the humility to say yes when yes is true.

And may we seek, above all else, that free and aspiring mind that leads us–not into self-display–but into Freedom and Excellence Infinite.

Leave a comment