Lucille Clifton gave us one of the most honest New Year poems in American literature. Many of us feel its truth in our bones. The poem begins:

I am running into a new year

and the old years blow back

like a wind

that I catch in my hair…

From the first breath, Clifton names a fundamental reality of human life: we are always moving forward while the past tries to pull us back—sometimes as a gentle breeze, sometimes as a storm that nearly knocks us over. We may want the next chapter, yet the previous chapters still flutter around us like pages the wind refuses to let close.

Everyone in this sanctuary knows those winds.

They come as memories—some cherished, some painful. They come as regrets that still sting, or as dreams we once held with bright conviction but which life eventually complicated. They come as promises we made to ourselves long ago—promises that were unrealistic even then, yet still seem to bind us. They come as old explanations for who we thought we were, or who we thought we needed to be.

Clifton continues:

it will be hard to let go

of what I said to myself

about myself

when I was sixteen and

twentysix and thirtysix…

She speaks here a spiritual truth rarely articulated so clearly: we are not shaped only by what others said about us; we are shaped—sometimes trapped—by what we once said about ourselves. The vows made in secrecy. The judgments whispered in shame. The identity stories formed when our understanding of life was still very small.

A teenager’s desperate promise.

A heartbroken adult’s vow never to be hurt again.

A perfectionist’s oath to be extraordinary.

A frightened child’s belief that they must earn love to deserve it.

These interior oaths echo much longer than the circumstances that created them.

And then the poem turns:

but

I am running into a new year

and I beg what I love and

I leave to forgive me.

This is the pivot point of the entire poem—a pivot from confession to release. She is not asking the world to forgive her. She is asking forgiveness from the parts of herself she loves and the parts she is now ready to leave behind. It is a prayer for spaciousness. A prayer for the possibility of something new. A prayer for a future not entirely determined by what came before.

And this is the moment when Tarot’s Fool enters the scene—dancing lightly at her side, stepping toward the cliff’s edge without fear, carrying nothing but a small knapsack and an open heart.

Tarot, for this sermon, is not about predicting the future. I’m using its images the way we use parable and poetry: to tell the truth slant, so we can tell it honestly.

The precious truth the Fool has to offer is about how to begin again.

As we cross into this new year, I want to imagine what the Fool might say to Lucille Clifton and to us—those who feel the old winds, those who want renewal yet feel tethered by the past, those who long to run forward but still feel the fingers of former selves holding on.

What would the Fool say?

What does the Fool know?

And how can that knowledge guide us into a more open, hopeful beginning?

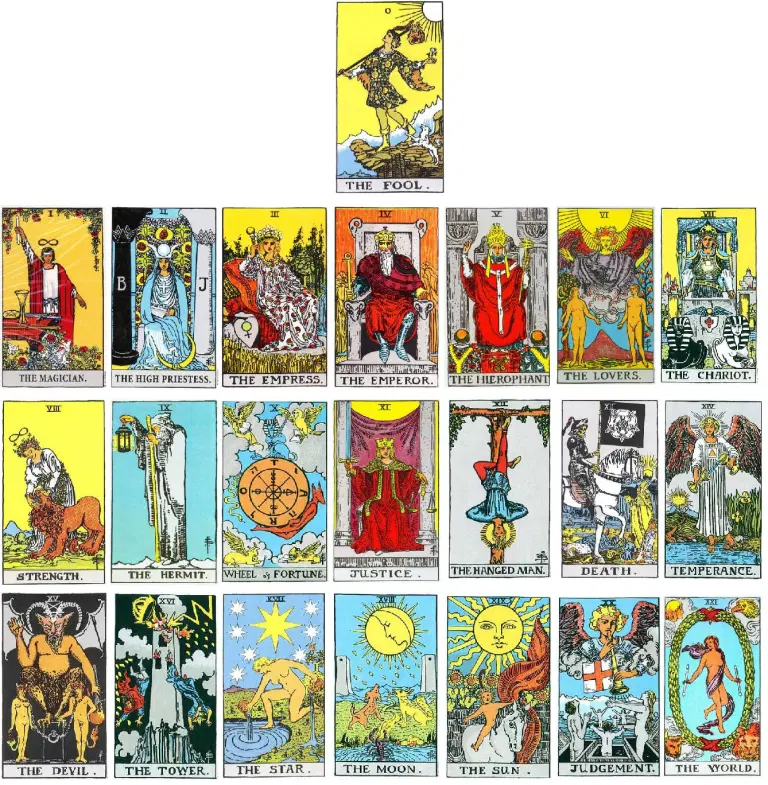

To answer that, we must remember who the Fool is in the great journey of the soul that Tarot’s Major Arcana symbolizes.

These 22 images are arranged as a pilgrimage—stages of human becoming. And one stands outside the sequence as its doorway: the Fool, card zero. Zero as the unnumbered origin, the seed of all becoming. Before the Magician claims power, before the High Priestess whispers mystery, before the Empress nurtures, the Emperor structures, the Hierophant instructs, the Lovers choose, or the Chariot sets out—the Fool simply is.

No résumé.

No predetermined identity.

No narrative about what success must look like.

No obligation to maintain past versions of the self.

The Fool embodies what Zen calls beginner’s mind: the clear, curious openness that greets life without assuming that the past must be the template for the future. It is the consciousness that has not yet become defensive, cynical, or brittle under the weight of expectation.

The Fool is not foolish in the ordinary sense. He is not reckless or naïve about danger. He is not blissfully unaware of how life can fracture us. The Fool knows cliffs exist and falling hurts. He simply refuses to let the fear of falling extinguish the joy of stepping. He trusts that the unknown is not primarily a threat but an invitation. He believes the world is not an adversary but a teacher. And he understands that life is not solved; it is lived.

So the Fool becomes our companion at the threshold of a new year. Not a cheerleader, not a disciplinarian, but a guide into the art of beginning again.

I imagine him approaching Clifton as she runs into her new year with the wind of old years catching in her hair. He does not stop her or correct her. He simply falls into step beside her and asks: “What would happen if you loosened your grip on the story of who you were supposed to become?”

“What would that look like?”

But let’s linger a moment with Clifton’s winds.

We all know what it’s like to feel blowback from the past. Old fears. Old insecurities. Old relational patterns. Old interpretations of ourselves that no longer fit who we are now.

We can be in a loving relationship and still hear the echo of the heartbreak that rewired our trust into hypervigilance. We can be sixty or eighty and still obeying a survival rule invented at twelve. We can be successful in our careers and still carry shame from an early failure that left a mark.

This is what Clifton means when she says it is hard to let go of what she once said to herself about herself. Our past selves are not gone; they live in us like layers of sediment—beautiful, complicated, and sometimes restrictive. We are shaped not only by what happened, but by the meaning we made of what happened.

The Fool looks at all this with compassion. He doesn’t ask us to erase the past; he simply invites us not to mistake it for destiny.

“The old winds are not failures,” he might say. “They are just weather. They come and go. You don’t need to build your house in a storm.”

When Clifton begs what she loves and what she leaves to forgive her, the Fool responds with a question that pierces the heart: “Why do you think you need forgiveness for becoming someone new?”

For many of us, guilt attaches itself to the act of change. We feel loyal to the identity we once fought to maintain, even if it limits us now. We cling to outdated promises because they were once our lifelines.

But the Fool says: Your former selves were stepping stones, not cages. They carried you as far as they could. They were never meant to last forever. “You may release an identity without betraying it,” he says. “You may thank a chapter without rereading it. You may take a step forward without asking your past self’s permission.”

This is the moment when hope quietly returns.

New Year’s culture often pushes us toward grand, sweeping resolutions—promises to become better, stronger, more disciplined versions of ourselves. The Fool smiles gently at this tendency. Not dismissively, but knowingly.

He might say: “The soul does not evolve through heroic vows. It evolves through small, courageous yeses.”

Right now, he is asking you: what might your small, courageous yeses be, in this new year of 2026?

This is why the Fool travels lightly. He does not drag trunks of old expectations. He does not carry suitcases full of perfectionistic rules. His knapsack holds only what truly matters.

Here are the spiritual practices the Fool offers at the turning of the year:

1. Carry only what you truly need. Curiosity. Trust. Responsiveness. Openness. Everything else—old grudges, outdated self-judgments, rigid expectations—can be set down.

2. Look for the next step, not the whole map. The Fool knows clarity comes from movement, not from knowing the entire route in advance.

3. Honor intuition before fear. Fear is allowed a voice; it is not allowed a vote.

4. Stay open to surprise. The Fool believes some of life’s best gifts arrive unannounced.

5. Distinguish scaffolding from cages. Some structures support us; others trap us. Wisdom is knowing the difference.

6. Forgive yourself for not knowing then what you know now. If you made a mistake, it’s because what you were facing was hard for you back then. If it had been easy, you wouldn’t have made the mistake.

What keeps Clifton running is not certainty, but self-compassion.

And now the sermon becomes personal.

Some promises were formed from hope. Others from desperation. Others from confusion. But the problem is that the reasons for the promises are long forgotten, though loyalty to the promises remains.

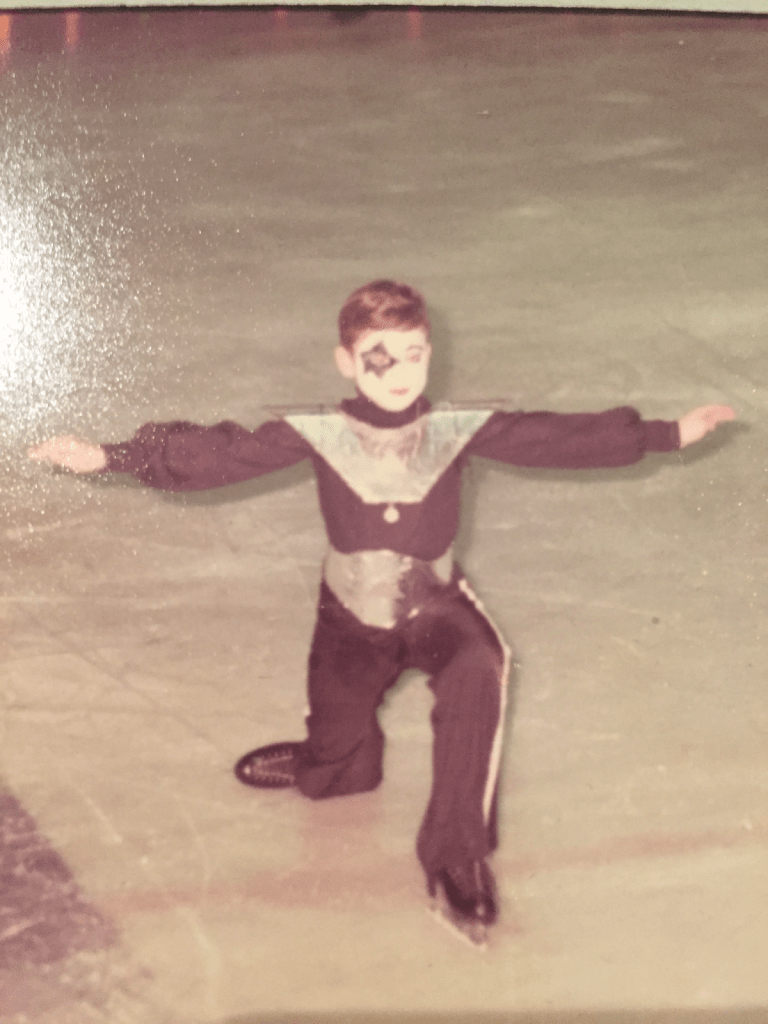

Recently, I was able to surface a promise I’d made long ago, and its reason. It was astonishing. It has to do with figure skating, which has always come with blowback for me. Never complete contentment. Always entering, or exiting, the ice feeling … disappointment.

It was when I was nine years old. My mother lived with profound mental illness. Life was constant chaos and pain. That was what I knew growing up. I wanted her to be well. I wanted her to be happy. I wanted her to be my mom.

But those were the cards I was dealt.

Then came the 1976 Olympics, which my family watched on TV. A very specific moment–when Dorothy Hamill skated what turned out to be a gold-medal performance. In that moment I saw my mother transformed. She lit up—cheering, clapping, fully alive in a way I had never seen. My nine-year-old mind was stunned.

And in that moment, I wrote a contract in my heart: If I could learn to skate like Dorothy Hamill and win Olympic gold, I could cure my mother. I could bring her back to full aliveness.

That’s why I began skating at nine years old. Going to the rink for practice at 5:30am before school started. Back to the rink after school. Here’s a picture of me from an ice show–apparently the rock band KISS was all the rage then:

I was committed. But the world around me changed. Dad moved my family from Alberta all the way to Texas–and back in 1978, let me tell you, Texas was a wilderness for ice skating. I had to hang up my skates. I had to accept that the Olympics was not ever going to happen for me.

Many years later, still living in Texas, I’d astonish myself by returning to the sport. This was 1998 and by that time, Texas had plenty of ice rinks. I would even go on to achieve success–gold medals at national and international adult skating competitions–but even so: it never felt like enough. Joy was always intermixed with disappointment. There was always this voice coming through–so quiet I could barely hear the words: You didn’t fix her.

The whisper of my childhood contract.

As I mentioned, only recently did I uncover the roots of that vow—how the child tried to make sense of the mother’s suffering, and in doing so, took on a responsibility no child could ever bear.

And here is where I’ve found the Fool so healing for me. To the nine-year-old who still lives inside me, he says: “I honor your longing. I honor your courage. You did the best you could with the tools you had. Thank you. But now, sweet one, you are released from the promises you made in confusion and fear. You are released. You are released.”

It will take time, I’m not going to lie.

Healing is a process.

But now it begins.

How might it begin for you?

What outdated promise might you still be serving?

What identity are you loyal to that has become too small for you?

We run into a new year together, you and I and Lucille Clifton. And if the Fool were among us, he would say:

“Run. Let the wind come. It is only reminding you where you’ve been.”

He would say:

“You do not need to fix the past before entering the future.

You do not need to complete your grief before taking another step.

You do not need to become the perfect self you once imagined.”

He would say:

“Forgiveness is not a transaction. It is a loosening.”

“You are not abandoning your former selves.

You are graduating from them.”

And finally:

“The only thing you must carry into the new year is the belief that your life is still unfolding.”

So to all of us—those with the winds of old years swirling around us, those holding outdated promises, those longing for a gentler story—the Fool offers this blessing:

May you trust the path enough to take the next step.

May you forgive the past enough to feel fully present.

May you release the identities that no longer hold your aliveness.

May you cultivate a lightness that is courage, not escape.

May you meet the new year not as a judge, but as a beginner.

For as Clifton writes, even while feeling the weight of what has been, she still chooses to run. “I am running into a new year” begins the poem. It sets the intention.

And the Fool whispers: “Yes. Keep running. The future is not a prison—it is a horizon.” A horizon that widens each time we soften our hearts, release an outdated vow, or take a step without demanding certainty first.

May this be your year of holy beginnings.

Your year of gentle forgiveness.

Your year of running with the wind at your back.

And may the Fool run beside you—

always pointing toward possibility,

always whispering, “You can begin again.”

Yes you can.

Leave a comment