Every living spiritual tradition eventually runs into the same argument.

Some people say, “Religion should be about changing the world.” Others say, “Religion should be about changing the self.”

One group wants the church to be a social justice organization with hymns. Another wants it to be a place of inward growth, healing, reflection, and meaning-making.

And usually-–if we’re being honest-–these groups don’t just disagree. They quietly suspect one another.

The activists worry that spirituality without justice becomes self-indulgent—an inward retreat from public responsibility. The contemplatives worry that justice without spiritual grounding loses its proper focus and becomes frantic, brittle, and exhausting.

If this tension feels familiar, it’s because it’s not new.

It runs straight through the Transcendentalist movement. And since we Unitarian Universalists are the spiritual descendants of Transcendentalism-–its inheritors—this tension runs straight through our congregations today.

This morning, I want to introduce you to a woman who did not resolve this tension, did not transcend it, did not theorize her way out of it–but lived inside it faithfully.

Her name was Lydia Jackson Emerson.

Let’s slow down and step into her world—set the Transcendentalist stage.

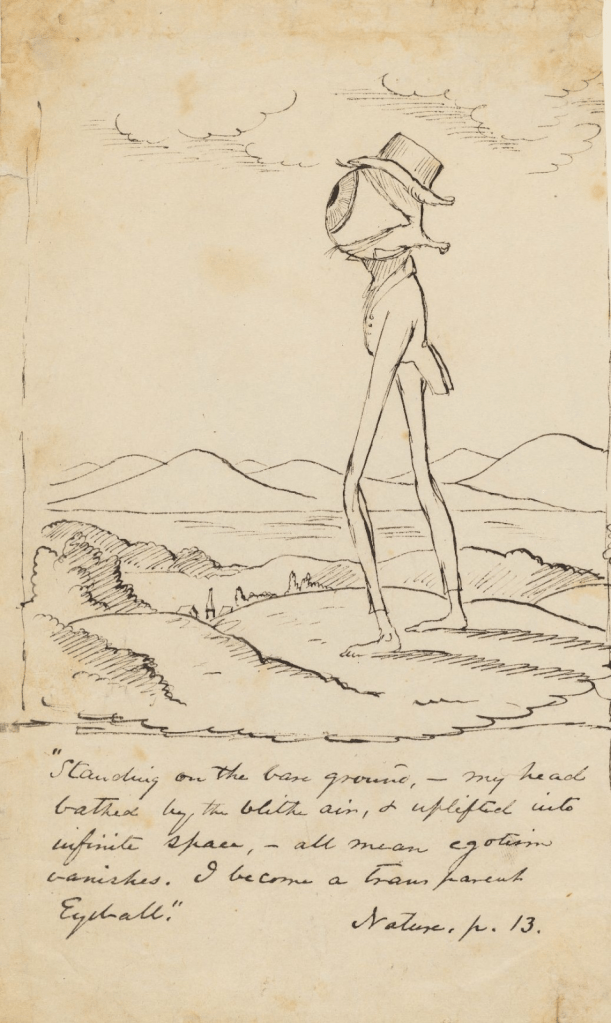

The common tendency is to imagine this famous spiritual and literary movement as serene: nature walks, intuition, poetry, self-reliance, and quiet spiritual confidence. But that image hides a more turbulent truth.

Transcendentalism was never a unified philosophy. It was a shared intuition—that something deeper than tradition, doctrine, or institution could speak directly to the human soul. Almost immediately, that intuition split into disagreement.

The disagreement wasn’t about whether justice mattered. It was about how change happens, with multiple dimensions:

- Regarding causality: Does the self shape society, or does society shape the self?

- Regarding time: Is reform gradual and organic, or urgent and interventionist?

- Regarding authority: Is conscience sufficient, or are institutions morally necessary?

- Regarding evil: Is injustice primarily personal ignorance and corruption, or structural and systemic violence?

Ralph Waldo Emerson believed that lasting reform must arise from transformed individuals. He was suspicious of movements, platforms, and moral crusades. He feared that activism without transformed consciousness would simply reproduce domination in a new form.

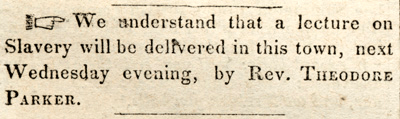

Others—like Theodore Parker—believed something very different. Slavery, war, and oppression did not need more patient reflection. They needed urgent, prophetic confrontation. Self-culture without reform would sanctify privilege and inertia.

These were not academic disagreements. They were personal. Emotional. Sometimes bitter.

And here is something important for us to hear, especially as Unitarian Universalists:

Neither side was completely wrong.

Spiritual depth without justice work can drift into irrelevance or narcissism. Justice work without spiritual grounding can lose its soul—use coercive means while preaching liberation. It can also burn people out.

The Transcendentalists lived this tension. And so do we.

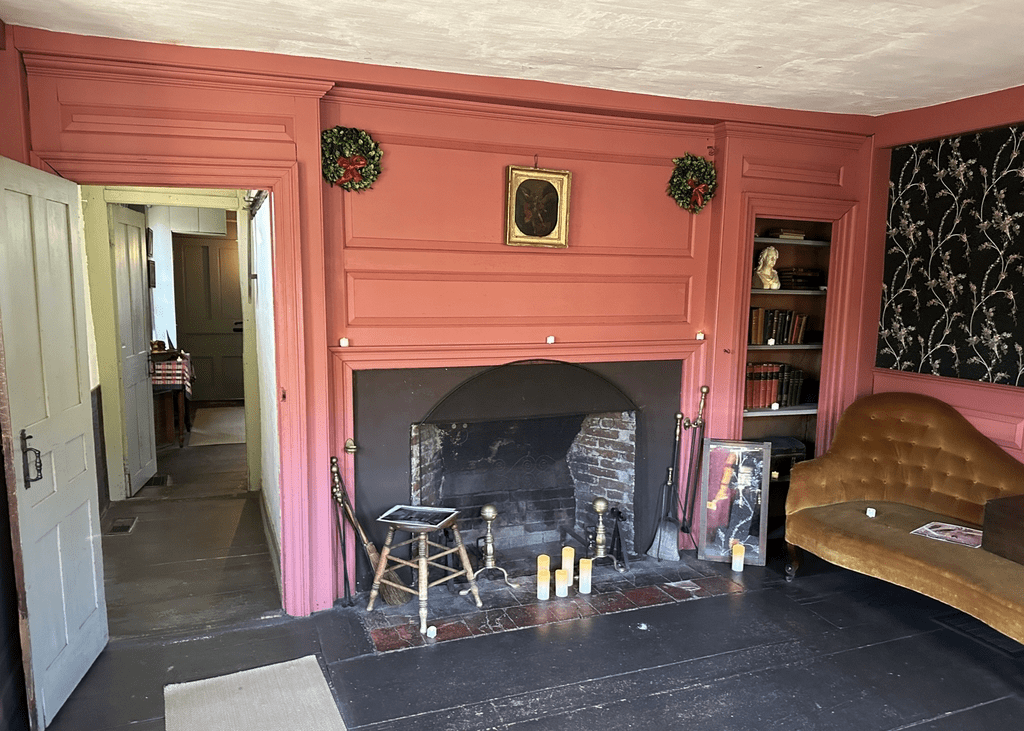

So now, don’t picture a movement. Picture a dining table.

Because these arguments were not only being fought in lecture halls and pulpits. They were being lived within households and in the midst of marriages.

In one such household, we meet Lydia Jackson Emerson.

She was born into a nineteenth century world that was not kind to women with serious minds. One male writer asked, in 1851, “What then shall the woman of genius do; what can she do, and be woman still?” Was her intelligence a gift—or a curse? Would it “unsex” her? Separate her from her kind?

This wasn’t fringe opinion. It was mainstream. And women absorbed it daily.

What does it do to a soul to be told your best mind makes you less of a woman? What does the daily diminishment feel like? How risky was the effort to push against it, to be fully woman and genius both?

Lydia took the risk. She was well read and loved literature, philosophy, religion, politics. She loved serious conversation. Her son later recalled that conversations often felt empty until his mother spoke—after which “all the fools went silent.”

She was not ornamental.

She was not deferential.

She was not content with small talk.

And that made her dangerous.

Lydia loved to argue. She loved disagreement. When she scolded her children for bickering, they learned to reply—using her own logic—“We aren’t bickering; we are conversing on various subjects.”

Even ministers were not exempt from her sparring. She delighted in challenging complacent authority. She was, by all accounts, combative, spirited, feisty.

She wanted to talk politics and religion, the latest novels, and—always—the sufferings of the poor and marginalized. She was an early advocate of abolition, women’s rights, and animal rights. Her religious feelings ranged all the way from orthodoxy to what some considered blasphemy.

In other words, Lydia Jackson Emerson was not temperamentally suited to quiet compliance.

Perhaps this is what made Ralph Waldo Emerson fall in love with her.

Lydia first encountered Emerson at a public lecture in Plymouth in 1834. Emerson later wrote of the charged moment when their eyes met—“a full, searching, front, not to be mistaken glance.”

Their courtship unfolded slowly, intellectually, intensely. Emerson wrote of the joy of finding “an earnest and noble mind whose presence quickens in mine all that is good and shames and repels me from my own weaknesses.”

Lydia, for her part, was both drawn and wary. She worried that marriage would narrow her life—and she was right. Emerson even persuaded her to change her name to the more romantic “Lidian.” (In this sermon I stay with her original name of Lydia.)

They married in 1835.

What followed was not a merging into harmony, but a lifelong conversation—sometimes tender, sometimes quarrelsome, always serious.

Most notably, Lydia was deeply religious in a way that often made her husband uneasy.

Her faith was not abstract. It was devotional. Personal. Morally urgent. She believed in prayer. She believed in conscience. She believed that God’s moral demands were not merely ideas to contemplate, but commands to be obeyed.

She was not opposed to inward spirituality. On the contrary—she took it seriously enough to believe that it must matter in the world.

She held two truths side by side:

- The inner life matters profoundly.

- And moral insight obligates outward sympathy and care.

She did not resolve this tension with a theory. She inhabited it as a way of life.

The consequence was a changed relationship to Transcendentalism itself. Before marriage, Lydia was attracted to its idealism, its seriousness, its promise of moral renewal. After marriage, living inside the movement cured her of any romantic illusions.

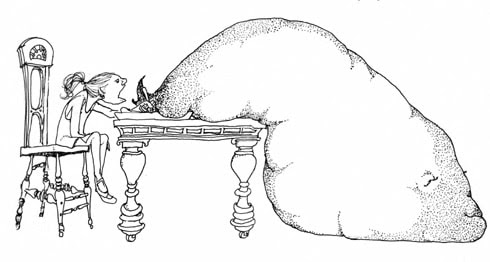

Picture Concord, Massachusetts–where stood the home that Lydia and Emerson shared. It became a Transcendentalist mecca. The parlor often saw self-proclaimed great souls gathered to speak of individualism. From today’s reading we heard them described as “talkers and faddists and dreamy hangers-on.”

And there is Lydia—keeping the room running while the men discoursed on freedom. Serving pudding while they praised self-reliance.

This wasn’t the only way she experienced a disconnect in Transcendentalism between ideals and reality.

She saw—early and clearly—that spiritual individualism, left unchecked, can make it easy to become oblivious to the collective injustices that are right before your very eyes.

Lydia did not float comfortably in Emerson’s world of philosophical detachment. She resisted it. She questioned it. She grounded it.

Her response to the Cherokee crisis makes this clear.

In the late 1830s, the U.S. government enforced a fraudulent treaty that enabled the forced removal of the Cherokee people. This was not abstract injustice. It was urgent, violent, and unfolding in real time.

Lydia wrote to a friend: “Doing good you know is all out of fashion, but there happens just now to occur a case so urgent that one must lay aside for awhile all new-fangled notions.”

Emerson privately resisted. Speaking out felt to him “like dead cats around one’s neck.”

But Lydia pressed him.

And he spoke.

He addressed a protest meeting. He wrote a letter to President Van Buren condemning “so vast an outrage upon the Cherokee Nation.” That letter was published nationwide—making Emerson one of the first non-Native public intellectuals to speak out.

Decades later, Lydia still took pride in this. “Your father is not combative,” she told her daughter—“with exceptions!” She called his letter an act of “great moral combativeness,” done against the grain, when no one else raised a voice.

What she did not say aloud—but history allows us to see—is that she herself was one of the pressures that made it harder for Emerson to live in clear conscience while staying silent.

If Lydia had measured her impact by public recognition or institutional authority, she would have felt powerless.

But she wasn’t.

Lydia exercised a different kind of power: moral influence.

She insisted that beliefs had consequences. That moral clarity must not remain theoretical inside their household. That silence in the face of injustice was itself a form of speech.

Over time, Emerson’s voice changed. Besides his denunciation of U.S. policy towards Native nations, including the Cherokee, he spoke more forcefully against slavery. He moved—slowly, imperfectly, but genuinely—toward public moral witness.

Did Lydia “cause” these changes? History is rarely that simple.

But she was one of the key forces that made him rethink his silence.

Let’s use a metaphor: social problems are whale-sized. Lydia’s action did not eat the whale. But she took the bite that she could take.

This matters enormously. Because most of us do not have the power to gobble up whale-sized problems in a single bite either.

Here is where Lydia’s life stops being history and starts being a mirror to us.

We live in a moment of overlapping crises. Some might call it living in a dumpster fire.

- Economic injustice that feels baked into the system.

- Racism and sexism that seem endlessly adaptive.

- The erosion of democratic norms.

- Environmental catastrophe.

- Geopolitical violence and instability.

- State sanctioned violence in our streets and beyond–and innocents murdered.

The problems are overwhelming. Every day–every day–something else! And many people are exhausted—not apathetic, not uncaring, but paralyzed by scale.

What a monumental task–just to keep up with the news cycle!

But we assume faithfulness not only requires 24/7 news vigilance, but fixing everything. That if we don’t know about everything and cannot fix everything, we have failed. That if we cannot address every injustice, our effort is meaningless. That if our action does not match the size of the problem, it does not count.

Lydia exposes the lie. The lie that only large actions matter.

That lie doesn’t make us faithful; it makes us freeze.

She did not ask, “How do I end slavery?” She asked, “What is mine to do, given who I am and where I stand?”

She models exactly the kind of question we must ask ourselves: Where is my leverage?

Not everyone is called to protest.

Not everyone is called to organize.

Not everyone is called to speak publicly.

Some people influence one other person.

Some influence a household.

Some influence a workplace.

Some influence a conversation that changes the moral weather.

Some people’s leverage is relational.

Some people’s leverage is financial.

Some people’s leverage is vocational.

Some people’s leverage is simply persistence—refusing to look away.

Lydia speaks directly to us today. Her leverage was influence—quiet, faithful, morally grounded influence—exercised without illusion and without despair. She did not try to eat the whale. She took the bite she could take.

And she trusted that others, elsewhere, would take theirs.

To those who say church should only be about justice: she says, without spiritual grounding, justice work becomes reactive, self-righteous, and a path to burnout.

To those who say church should be only about inner growth: she says, without moral consequence, spirituality becomes escapism.

She refused the black-and-white thinking underlying the mentality of “church should be only this.” She shows us a faith that tends the soul and refuses injustice.

Let me offer something explicitly this morning: relief.

You are not required to solve everything.

You are not failing if your reach is limited.

You are not unfaithful because your capacity is finite.

Your worth is not measured by how much outrage you can sustain.

You are allowed to rest without giving up.

The question is not, “How do I fix this?”

The question is, “What is mine to do?”

Regarding your influence, ask: who listens to me?

Regarding your money and time, ask: what is at your disposal, which you honestly can give?

Regarding your presence, ask: where can I show up, because if I don’t, something dies in me?

Lydia Jackson Emerson shows us that faithfulness does not require heroics—only honesty, courage, and perseverance with pauses so it remains sustainable.

The Transcendentalists never resolved the tension between spiritual individualism and prophetic justice. Neither will we.

And that is not a flaw. It is our inheritance.

You and I are here today to trade in courage–so no one has to take their bite alone.

May we live inside the tension with integrity.

May we take the bite that is ours.

And may we trust that, together, the whale can be eaten.

Leave a comment