Dear Jesus,

I am writing to you as one of your very distant descendants in the life of faith—a minister in a religious tradition that, oddly enough, would not exist without you, and yet does not look very much like what most people today call “Christianity.”

It’s called Unitarian Universalism.

In some ways, I think you might recognize it as one of the many unexpected children of your movement—a religion that grew out of Christianity, argued with it, wandered from it, and is still, in its own way, trying to follow the same currents of love, truth, and liberation that once carried you across Galilee.

People often ask us, “What is Unitarian Universalism?” We talk about “elevator speeches”—quick answers delivered between the first and fifth floor. But you deserve more than an elevator speech. I want to tell you about the essential beliefs that animate us now—what your message eventually gave birth to in this branch of your spiritual family tree.

Think of this as a report from one of your far-flung, sometimes exasperating, often beautiful descendants.

1. We believe the basic spiritual problem is ignorance, not original sin.

Over the centuries, many of your followers came to see the central human problem as sin—an inherited brokenness in the soul, traced back to the first humans. Some theologians declared this flaw so absolute that only supernatural intervention, often understood through your sacrificial blood, could make us whole again.

I can’t pretend to know what you would think about this, but here’s how it landed in history.

Our tradition sees things differently. We do not deny that people can commit terrible harm. We know they do—and sometimes they do it with their eyes open, fully aware that someone else will suffer. Even in your own name, Jesus.

But we have learned to ask a deeper question: what story is a person telling themselves as they do it? What “good” do they think they are serving?

Here we find wisdom in something Socrates once argued: no one does evil knowingly. Not because people are unaware of harm, but because human beings almost always act under a self-justifying picture of the good—necessary, righteous, deserved, for the greater purpose. They may know they are breaking eggs. What they do not see—what they cannot yet see—is the full meaning of what they are doing: the long reach of consequences, the way harm spreads through a community, the way it hardens the soul, the way it deforms the very “cause” they believe they are serving.

So we do not say the human heart is rotten at the core. We say the human mind is limited—and those limits can be trained, rewarded, and defended, especially when they shore up a sense of moral superiority. Sometimes that superiority is rooted in social privilege. Sometimes it grows out of resentment—real pain that hardens into moral inversion: my suffering proves my goodness; your strength proves your evil. In either case, moral vision narrows, and the good is mistaken for the merely justified.

This is how the soul poisons itself: by confusing the justified with the good. Ignorance—not stupidity, but unawakenedness—is the heart of the problem.

We still laugh about the tale of the roast with both ends cut off because “that’s how Grandma did it”—long after the original tiny pan is gone. But when we look at racism, sexism, tribalism, greed—cycles of harm passed down because “that’s how we’ve always done it”—laughter catches in our throats.

Jesus, we think you understood this. You said, “You have heard it said… but I say to you…” You knew people could be trapped by inherited certainties and moral slogans that felt righteous while doing damage. You tried to wake them up. And so we, in our way, try to continue that work.

2. We believe the cure for ignorance is found in many sources of wisdom, not just one.

Over time, many of your followers came to believe that saving truth was scarce—confined to one people, one prophet, one book, one authorized set of doctrines. In this view, you were not just a teacher but the single, unrepeatable exception to humanity: the only full incarnation of God.

In the nineteenth century, a Unitarian minister named Ralph Waldo Emerson stood in the Harvard Divinity School chapel and said, as gently as he could, that this “spiritual scarcity” was a mistake. He called it the “idolatry of Jesus”—not to reject you, but to insist that divinity does not live only in you.

If all the light is in you, then there is none left for anyone else.

But if the divine spark is in every person, then you become not a monopoly of God but a model of what human beings can be.

So we learn from you, Jesus—your courage, your tenderness, your imagination, your power to break open false certainties. But we also learn from the Buddha, from Muhammad, from the prophets of Israel, from Mary and Miriam, from scientists, poets, philosophers, mystics, and indigenous wisdom keepers. We learn from nature, from children, from moments of wonder.

Revelation, for us, is not scarce. It is abundant.

The world is shimmering with insight—music, art, forests, the night sky, grief, friendship, scientific inquiry. The challenge is not finding wisdom; it is deciding where to begin. And the answer, for us, is simple:

Begin where you are.

Begin with the life you’ve been given.

Begin with the question burning in your own heart.

3. We believe each person must actively claim their spiritual life.

Long after you were gone, the Church developed systems of sacrament and authority. Infants were baptized into the faith before they could speak, their spiritual identity defined for them by clergy and empire.

In the 1500s, a group of “troublemakers”—our spiritual cousins—objected. They were the Anabaptists. They insisted that baptism should be a conscious choice, an act of integrity, not something done to you before you could consent. They paid for this with their lives. But their question remains alive in us:

How can there be a genuine spiritual life without a genuine yes?

Today the pressure is different. It is not infant baptism. It is the crushing speed of modern life. People are exhausted, overloaded, overstimulated. Children are scheduled like corporate executives. Adults bury their souls beneath productivity and screens. Weekends vanish into errands and catch-up sleep.

To live spiritually in such a time requires two forms of effort:

First, there’s defensive effort: the courage to say no to the forces that flatten the soul—endless productivity, constant accessibility, the pressure to optimize every moment.

Next, there’s creative effort: the willingness to say yes to practices that awaken the deeper self—prayer, meditation, silence, service, study, creativity, worship, community.

We often compare it to musical talent. Some people are born with an ear for music; others are not. But no one becomes a musician without practice. And no violin sounds beautiful in the beginning.

Likewise: every human being has a spiritual instinct. But if it is never trained—never questioned, never stretched—it can warp. It may attach itself to destructive ideologies, charismatic leaders, nationalism, supremacy, violence. When the inner life is neglected, what is best in us can become what is worst.

So we tell our people:

You must participate in your own unfolding.

Grace may be free, but growth is not effortless.

4. We believe spiritual individuality requires nurturing community.

Jesus, we do not believe in “do-it-yourself” religion. No one is self-made—physically, emotionally, or spiritually.

From our beginnings, the ancestors of Unitarian Universalism insisted on three freedoms:

Freedom of the pulpit. Ministers must speak honestly, even when inconvenient.

Freedom of the pew. No one is coerced into belief.

Separation of church and state. Faith must never be enforced by the sword.

Our oldest churches in Transylvania–yes, Dracula country—testify to this. Those early Unitarians proclaimed that no one should be persecuted for their beliefs. Many were killed. The churches that survived are sanctuaries of spiritual freedom.

We carry that inheritance forward.

We believe the congregation is a workshop for the soul—a place where your questions are welcomed, your doubts are taken seriously, your conscience is honored. A place where you can tell the truth about your life without fear of condemnation.

In worship, we gather not to recite a single doctrine but to awaken imagination and love. In religious education, we expose people—especially children—to the best of human wisdom from many cultures. In small groups, we practice listening deeply. In our democratic structures, we learn responsibility, dialogue, compromise, and shared leadership.

Michelangelo said every block of stone contains a statue; the sculptor’s task is to remove what hides it. We believe each person carries a spiritual design—a truer self, a divine image.

Spiritual community is the studio where the chiseling happens: not to impose shape, but to reveal it—removing shame, fear, false beliefs, and self-righteousness.

In this sense, community is not optional.

It is how the soul grows.

5. We believe freedom has limits: no spiritual path justifies harm.

We cherish freedom of belief. In our pews sit Christians, Buddhists, atheists, pagans, Jews, agnostics, seekers, skeptics, and spiritual hyphenates who defy category. Our walls even proclaim, “We need not think alike to love alike.”

But this freedom is not absolute.

It ends where one person’s conviction becomes an excuse to injure another.

When religious belief leads to:

- violating another’s agency or consent

- diminishing others through gossip or deceit

- emotional or physical abuse

- racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia

- any authoritarian ideology of dominance or supremacy, from right or left

the community must say: No. That crosses a line.

We use covenants—promises about how we will treat one another. Not creeds that dictate belief, but commitments that guide behavior.

Your teaching, “By their fruits you shall know them,” still governs us. Whatever name someone gives to God—or whether they use the name at all—if the fruit of their path is cruelty or domination, something is wrong at the roots.

Freedom is sacred.

Harm is not.

6. We believe spiritual growth moves us toward a larger sense of self.

You spoke of losing one’s life to find it. We hear in that not a call to erase the self, but to expand it—to grow beyond the cramped “I” that imagines itself separate from everything else.

Inside us is the daily monologue: anxieties, to-do lists, resentments, fantasies. It is shaped by our identities—race, gender, class, nationality, age, ability. When we live entirely inside that interior storm, life becomes small.

And yet something in us longs to belong to something larger.

We imagine concentric circles:

at the center, the everyday ego;

around it, circles of family, community, humanity, the earth, the great mystery.

Spirituality is the process of shifting our center of gravity outward. We still have a self—but it becomes porous, connected, responsive. Our joy expands. Our heartbreak widens. Love becomes more spacious.

M. Scott Peck called love “the will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth.” Love is not passive. It stretches us. It seeks our flourishing and our neighbor’s flourishing. It is risk-taking and patient, tender and fierce.

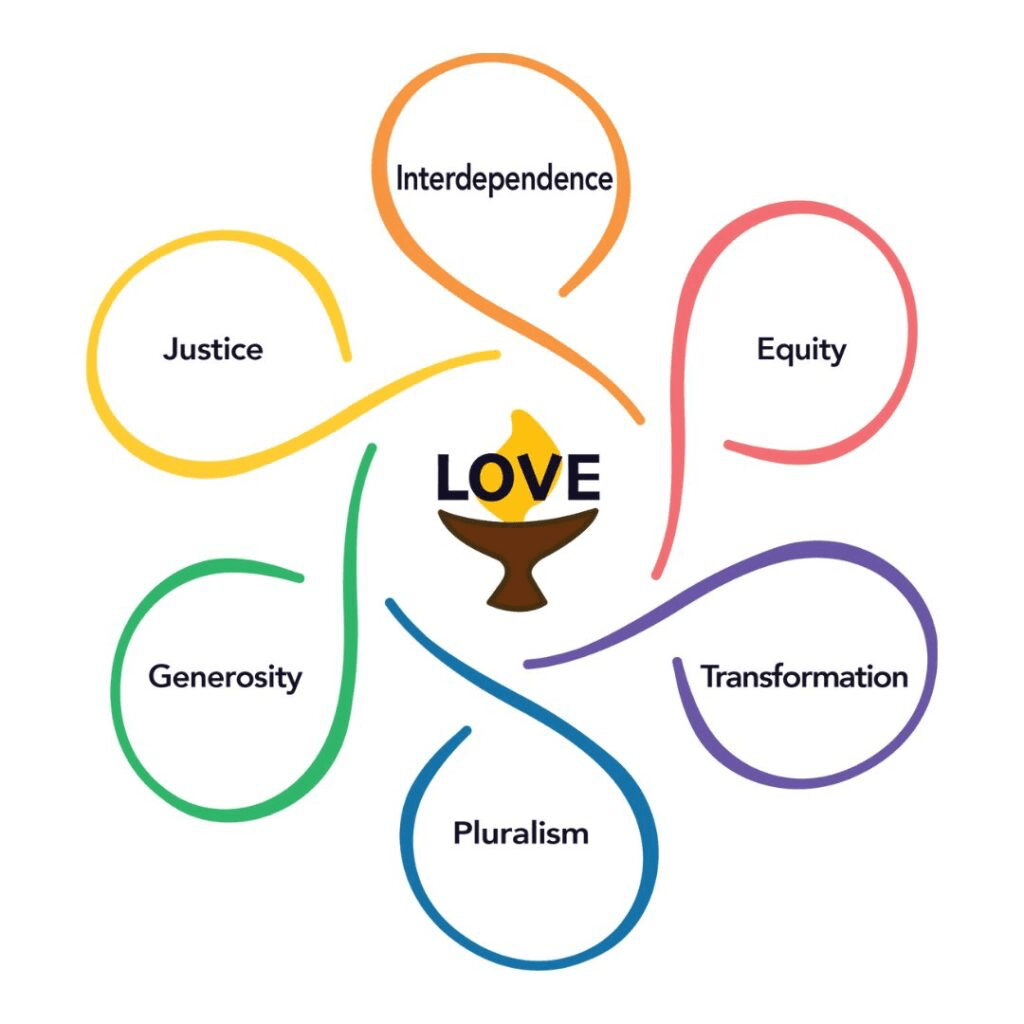

This love naturally grows into justice. That is why our UU Association recently named interdependence, equity, transformation, pluralism, generosity, and justice as core values.

These are not abstract words. They are what love looks like in public. They are the outward shape of inward truth.

I think you would recognize that.

7. We believe the goal of spirituality is depth and richness in this life.

Much of Christianity has focused on the afterlife—heaven, hell, salvation beyond the grave. We do not dismiss these questions, but our emphasis is here and now.

E. B. White once wrote, “I arise in the morning torn between a desire to improve the world and a desire to enjoy the world. This makes it hard to plan the day.”

We understand this tension.

Our spirituality tries to hold both:

To enjoy life: beauty, joy, friendship, humor, rest, art, music, nature.

To mend the world: justice, compassion, courage, repair, truth, resilience.

If we only see the brokenness, we break.

If we only chase pleasure, we stay shallow.

So we ask not merely, “What do you believe?” but “How do you live?”

This, for us, is the heart of religion:

Not escaping life, but entering it more fully.

Jesus, this is the religion that grew from yours.

We are not always easy children.

We question doctrines wrapped in your name.

We insist on freedom where others insist on obedience.

We can wander so far from traditional language that people wonder whether we count as “religious” at all.

And yet we are still wrestling with the same questions you lived:

What does it mean to love our neighbor?

How do we awaken people from destructive ignorance?

How do we honor the divine spark in each person?

How do we create communities where the soul learns balance?

How do we live so that death does not have the final word—not because we escape it, but because love outlasts it?

If you walked into one of our congregations on a Sunday morning, I’m not sure what you’d think at first. You might be surprised by the absence of creed, by the variety of beliefs, by hearing your name honored but not required as the sole doorway to the holy.

One week the music is all classical; the next it’s rock-and-roll.

One week, the sermon might be about you; the next it’s the spirituality of Star Trek.

You may wonder about the variety.

We do it because truth doesn’t wear only one set of clothes.

But I hope you would recognize something:

In the way we make room for conscience.

In the way we center love as the measure of truth.

In the way we gather not to claim exclusive access to God but to remember that none of us is alone.

In the way we struggle—imperfectly—to repair a hurting world.

In the way we seek depth, courage, and joy in this life.

I hope you would see, in our Unitarian Universalist way, one more experiment in the long unfolding of the faith that began with you.

From one very late descendant in your spiritual family,

with respect, gratitude, and a hopeful heart,

Anthony

Leave a comment