Over the past several months, we’ve been traveling together through historical Transcendentalism—not as literary appreciation, not as a charming stroll through nineteenth-century New England, but as a living conversation with our own Unitarian Universalist inheritance.

Again and again, we’ve been asking the underlying question: why did this movement arise when it did, and why does it still speak so directly to congregations like ours today?

This morning I want to suggest one reason:

Transcendentalism was born in a time of cultural acceleration, social upheaval, and moral exhaustion.

Sound familiar?

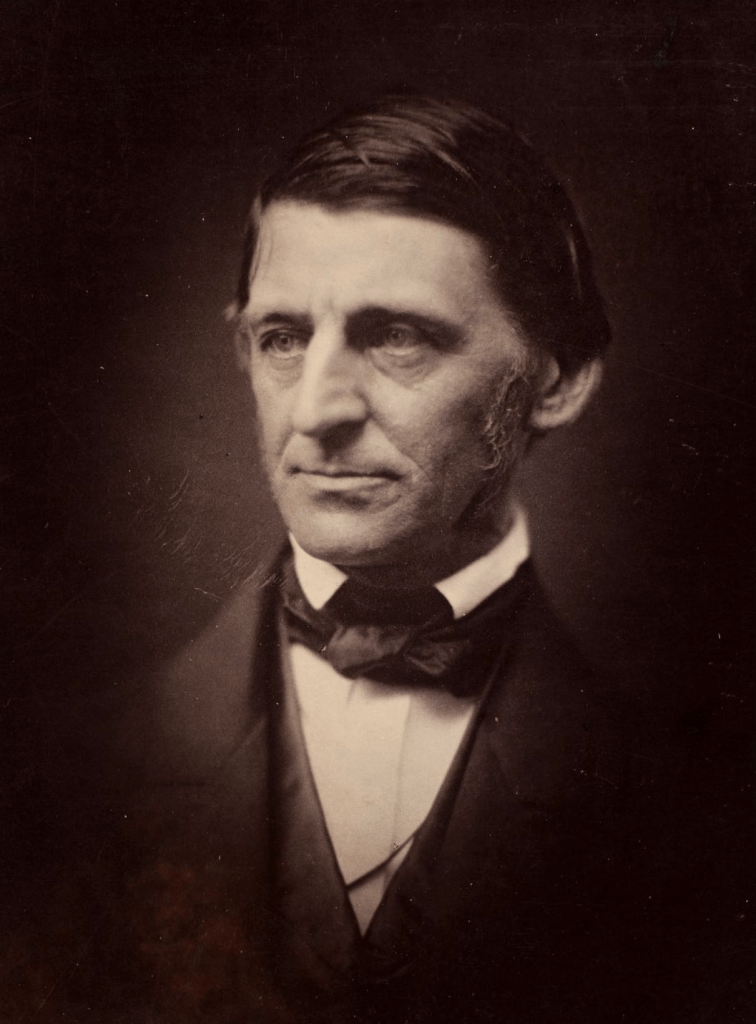

Ralph Waldo Emerson and his circle lived through rapid reorganization—industrialization, technological efficiency, economic expansion—and a growing habit of mind that prized utility above almost everything else. Railroad tracks were crisscrossing the land. Towns were reshaped around mills and markets. Life was increasingly measured, scheduled, optimized.

And beneath it all was a quiet, profound fear: What happens to the human soul when everything is evaluated by usefulness alone?

That question has not gone away. If anything, it has intensified.

Many of us now live in compressed urgency. The pace is relentless. The news cycle is unending. The crises—personal, communal, planetary—feel immediate and overlapping. Even when we’re doing meaningful work, the nervous system can start living in permanent contraction. Shoulders rise. Breath gets shallow. Even rest can start to feel like another task.

So the question isn’t, How do we become less responsible?

It’s this:

How do we stay engaged without becoming spiritually flattened?

How do we meet real urgencies without letting urgency pretend it’s depth?

Before I go further, let me offer a small doorway—right here, right now.

Take one slow breath. Let your jaw unclench. Feel the weight of your body supported—by the chair, by the floor. Notice one sound you didn’t make. One small sign that reality is larger than your to-do list.

That widening—small as it is—is the point.

And I know it’s real because I’ve seen it happen in this community.

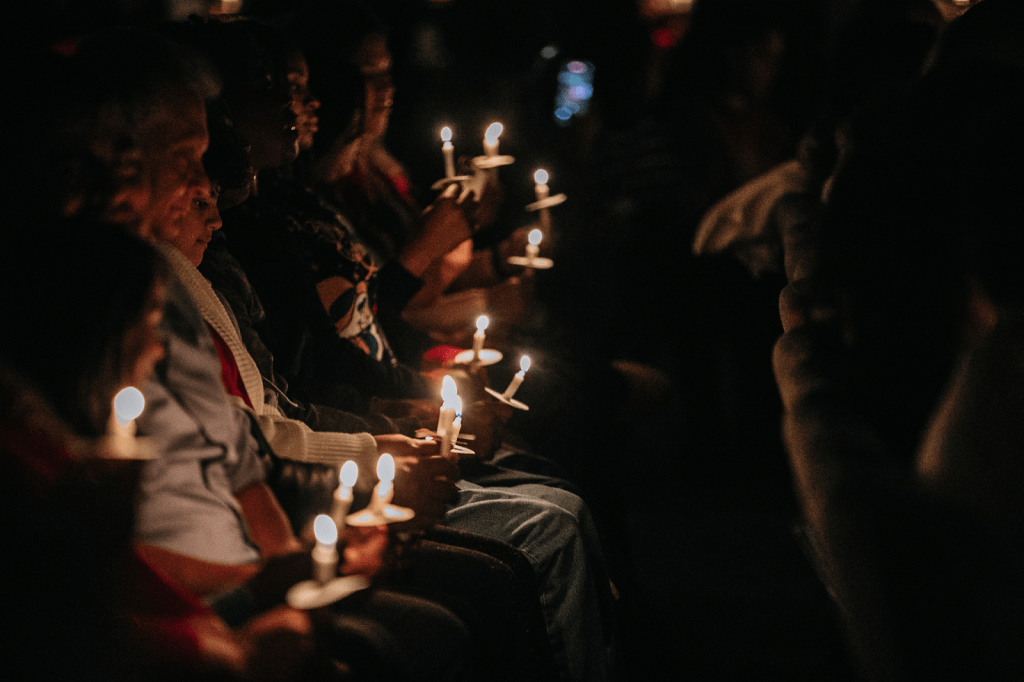

I’m thinking of the candle-lighting ritual we do every Christmas Eve here. One flame is passed from candle to candle—again and again—until the sanctuary fills with hundreds of points of fire. And as the light spreads, the overhead lights dim in proportion, until they’re turned off completely.

For a few minutes, from the chancel, I can see only what each person holds: one steady flame, a face softened into shadow, and a hush you can almost feel.

One Christmas Eve, in that darkness threaded with light, I felt something open in me.

So much of what usually divides us fell into the background: our clothes and status; our age and achievements; the labels we carry; the tribes we belong to; the opinions we defend. For a moment, the noise of ordinary life—with all its sorting and judging—simply receded.

And what I saw—what I think the God of my understanding sees—was this:

Beneath the postures and the wear-and-tear, we are shining points of light. Souls in process. Lights equal in compassionate sight.

And when I can see another person through that lens—even someone I strongly disagree with, even someone I don’t understand—I am changed. I have more patience. More humility. More willingness to stay in the room and keep working toward healing. I remember my own mistakes, and I become less eager to reduce another person to one moment, one stance, one story.

This is the shift Transcendentalism is trying to protect: a human life that doesn’t collapse into the narrow band of the tactical, judgmental mind alone.

And now I can name that shift with a word that’s become increasingly useful in today’s spiritual psychology:

Transpersonalism.

“Transpersonal” names experiences in which the cramped ego-self relaxes and a wider identity becomes available—compassion larger than preference, love larger than fear, moral clarity larger than social conditioning, belonging larger than isolation.

This sermon is about learning to widen on purpose.

Not to escape the world—but to meet the world from a deeper place.

This is where Emerson enters—not as a literary icon, but as a Unitarian ancestor who offered a practice of consciousness for exactly this kind of moment.

In his essay Nature, Emerson says many people “work in the world with the understanding alone.” By this he means: we engage reality through the senses, through calculation, through management—the part of the mind that measures, categorizes, optimizes.

He calls it “penny wisdom”—a life reduced to increments, transactions, and utility. And he says bluntly that when this becomes our only mode of engagement, something essential is lost. A person becomes only “a half” human being: capable, competent, effective—and yet strangely diminished.

Now Emerson can be confusing because he uses the word Reason in an idiosyncratic way. For him, Reason is not linear thinking. It is spiritual intuition—a higher mode of knowing that apprehends moral truth, beauty, and spiritual reality directly. He contrasts that with “the understanding,” the mind that analyzes and controls.

So to keep Emerson faithful and keep us clear, I’m going to use two phrases:

- Instrumental thinking: the calculating, managing mind Emerson calls “the understanding.”

- Spiritual intuition: what Emerson calls “Reason”—the inward capacity to perceive meaning, conscience, beauty, holiness.

That’s the axis of his argument: not anti-intellect, but more than intellect; not irrationality, but a larger way of knowing that restores wholeness.

And we should be clear about what Emerson is not saying. He’s not rejecting empiricism. He’s not attacking science. He’s not romanticizing ignorance. He was intellectually rigorous and deeply informed.

What he challenges is the reduction of reality to what can be bought and sold, controlled, and optimized. He warns about what happens when the managing mind colonizes every other way of knowing—when everything becomes a “problem to solve.”

But love is not a problem to solve.

Beauty is not a problem to solve.

Grief is not a problem to solve.

Conscience is not a problem to solve.

God—however you understand God—is not a problem to solve.

They are mysteries to be lived.

And here’s a simple return to our thread:

this is my candlelight seeing.

This is the widening.

To understand Emerson’s intensity, remember his context. In the nineteenth century, “enthusiasm” was a suspicious word. It didn’t mean pep. It meant religious excess—spiritual intensity that respectable people distrusted. Enlightened modernity was supposed to be sober, controlled. Any claim of direct spiritual perception could be dismissed as fanaticism, or delusion. Best kept at arm’s length.

Emerson did not accept that verdict. And part of why is that he was tutored—quite literally—by his aunt, Mary Moody Emerson: intense, spiritually demanding, morally fierce. She helped transform the era’s distrusted “enthusiasm” into something else—into mysticism in the best sense of the word.

And if “mysticism” sets off your inner skeptic, stay with me: I’m talking about experience, not superstition. Not escape from the world—contact with depth. Mary taught Emerson that the soul has its own instruments: a way of knowing that does not cancel intelligence, but completes it; a way of seeing that widens the self instead of narrowing it.

Emerson names our predicament: when we live from the managing mind alone, we become dulled, cramped—less than fully alive.

He’s not telling you to throw your phone into Lake Erie and become a forest hermit. He’s saying something subtler and more searching: if the only authorized tools for reality are senses, technology, and instrumental thinking, then we will treat everything as if it were a problem. And crisis consciousness can trap us there even when our intentions are noble.

When you’re flooded, the mind narrows. You become efficient. Reactive. Tactical. And—understandably—you lose access to depth.

So the pastoral question becomes:

How do we widen again?

How do we return to a self that can act, but not panic; care, but not collapse; engage the world, but not be devoured by it?

Emerson’s answer is a kind of opening. In Nature, he describes stepping into the woods and feeling the ordinary ego loosen and he becomes, in his famous image, a “transparent eyeball.”

He’s not just describing a nice walk. He’s making a theological claim: human beings are capable of moments when the ego relaxes, and a larger reality becomes available.

And the effect is not escapism. It is re-orientation.

A person remembers: there is more going on than the crisis. There is a depth that was here before the emergency and will be here after it. There is a sustaining reality—call it beauty, call it the holy, call it the currents of universal belonging—that can hold us when our own inner resources feel spent.

Now I want to speak directly to our moment.

One of the striking developments of contemporary culture is the enlistment of spirituality as a workplace best practice. Meditation becomes a business tool to focus longer. Mindfulness becomes a way to tolerate more stress. Purpose becomes a way to work even harder. Belonging becomes a way to increase loyalty to the job.

None of these are automatically bad. Many are genuinely helpful.

The danger is when the deeper life is permitted only insofar as it serves productivity—when interior life becomes another resource to manage. The soul becomes one more asset. Spirituality becomes acceptable as long as it doesn’t actually widen us beyond the systems and pressures that demand constant output.

And here is the pastoral cost: people begin to feel that even their spiritual practices are just another item on the to-do list. Another optimization strategy. Another way to keep going when they are already depleted.

Some of you are exhausted—not because you’re doing nothing, but because you’re doing so much while spiritually starving. You’ve been trying to meet the world from the narrowed band of the tactical mind alone: coping, managing, pushing through.

And Transcendentalism—when it’s more than literature—offers a mercy:

You do not have to meet the whole world with your own small self.

You can be supported by what is deeper than any momentary crisis. Not by denial. Not by spiritual bypass. But by lived connection to the depth layer of reality: widening so you can tell the truth, bear the truth, and still keep your heart.

And if you’ll allow me—this is where I can say, not only that I’ve seen widening happen in this community, but that I learned its necessity very early.

Here is the story. My two brothers, my dad, and I essentially lived in our garage. The house was where mom lived. The rest of us made do with what was left.

It’s because this was the safest arrangement we could make. Mom wasn’t well—was dangerous at times.

It’s not something I told friends. If I played with someone after school, we went to their house.

Our garage fit two cars. Dad built our living space in the area meant for one. The other bay was completely taken up by my mom’s green Datsun, with its oily smell.

Our beds were mattresses that sat on examination-room tables. Dad showed up one day with four of them. Until we needed them, they stayed stacked in the only closet. We had to keep the room as uncluttered as possible.

There was a long desk with chairs that slid underneath, and shelves along the wall. It was one common room, and each of us chose which places would hold our stuff.

Sometimes I took a favorite record album cover into the closet. I’d climb on top of the stacked mattresses and roll the door closed, leaving a crack of light. One of those albums was Trying to Get the Feeling by Barry Manilow. The cover showed a funny sculpture of him at the piano—smiling, hair over his eyes, his long fingers playing away.

There was no way to drag a record player into the closet, so I just stared at the cover and sang the songs I could remember over the muffled sounds outside.

My favorite was “I Write the Songs.”

I didn’t understand everything it meant. But I understood the feeling: that music could make you brave, could make you move, could make your heart feel like a place worth living in. The chorus ended with a phrase I held onto—a worldwide symphony.

Even in that dark, cramped space, I could feel something in me widen—bigger than the room I lived in, bigger than the garage, bigger than the smell of oil.

Widenings like this is why I didn’t give up—what kept hope real in the midst of family chaos growing up.

So when I say “transpersonal,” I’m not offering a fashionable idea. I’m naming a human capacity that can keep a soul alive.

Widening experiences can come through many doorways: nature, meditation, prayer, music, art, athletics, dreams, love, service. They can come through awe, grief, joy—quietly or dramatically. What they share is this: they loosen the tight knot of self-concern and reconnect us to a wider field of meaning.

And here’s the practical question:

How do we choose that doorway—on purpose—when we’re living under pressure?

Isn’t America right now one big family chaos? And that’s what we all need—keeping hope alive.

It doesn’t have to be heroics. Doesn’t have to be dramatic reinvention.

Just this: choose one doorway to the “more.”

Three minutes outdoors—no phone—just enough to let the world be radiant again.

One piece of music with your eyes closed, letting your body remember it is alive.

One act of compassion that interrupts the ego’s habit of isolation.

One honest conversation in which you share—not only what hurts, but what has ever made you feel wonder.

Abraham Maslow noticed something simple and hopeful: when people remember and speak about their peak experiences, they often become more available to them. Naming the possibility opens the door.

So share your stories—not only of pain, but of wideness. Not only of struggle, but of moments when you felt held—and found your footing again.

Because this widening of the self is not a luxury. It is not escapism. It is sustenance.

Let our religion be true.

The deepest thing that’s real is not our urgency. The deepest thing that’s real is the radiance beneath things. The love that outlasts our crises. The moral beauty that keeps calling us forward. It is the depth Mary Moody Emerson dared to trust, and Ralph Waldo Emerson dared to name—and that our tradition still needs, not as ornament, but as nourishment.

May we be widened.

May we be re-rooted.

May we be supported by what is deeper than this moment—

so that we can serve this moment without being consumed by it.

Leave a comment