One of my personal passions which you may or may not know about is yoga. The journey of any given yoga class from beginning to end is, first of all, unrolling my 68 inches long and 24 inches wide mat on the floor and getting on it, and this will become the center of my universe for an hour. During that hour, living becomes a flow of steady breathing in and out, in and out, while entering into a pose, then leaving it, then moving into another pose, and so on–which to me has always resembled what ordinary life is like, with its own sort of poses, and all its comings and goings.

Sometimes I am even lost to myself, and the flow becomes all, and finite and infinite become One.

But sometimes, the reverse can happen, and I find something I’d rather not, and I feel even more stuck inside the finite than usual.

It can look like this. I’m on my mat and I’m in one of those pretzel-looking yoga poses. Surrounding me are all these other people, each on their own 68 inches long and 24 inches wide mat, in the same pretzel-looking pose as me. But maybe their pose is not as “good” as mine. See, that’s where my mind goes. I’m judging the other yogis around me. I’m comparing–and I’m invoking, rather pretentiously, the Sanskrit names of the poses as I do this, as in: My Adho Mukha Svanasana is so more fully expressed than theirs! My Vrikshasana is so much more stable! I can do Shirshasana and they can’t!

And so on. The judgmental inner voice comes, I feel an accompanying tension and clench of muscles, my breathing gets shallower, and swiftly following all this is shame. It’s more of the inner judgmental voice, but this time, I’m the target. As in: What’s wrong with you? Who do you think you are? Look at that yogi over there! She can do Adho Mukha Vrikshasana and you can’t! So much for you, Mr. Senior Minister yoga-man!

And so on. The judgmental dialogue spontaneously unfolds, just like it does off the mat in real life. The only difference is that when I’m on my mat, I’m invited to bring greater awareness to what’s happening inside me. The mat is the symbol of that. Unrolling the mat and getting on it is a ritual way of saying, “I give myself to the flow of my experience. I will be curious about it and follow it wherever it leads.”

That judgmental voice: it’s like a crazed monkey with a baseball bat, in a tiny room full of delicate and beautiful glass sculptures. The judgmental voice smashes one way, then another. Others are the target, yes, but you and I were the target first.

Let’s step back to see the larger story.

You and I were born into a social world that ruthlessly sorts us according to whichever identities are ours, based on a value agenda that is all its own. You and I are born, and our tiny bodies bear a certain skin color, and we’re judged about that. We are born, and our tiny bodies come with certain sex organs, and we’re judged about that. Born, we possess congenital disorders, or we don’t, and even more judgment comes our way.

Good or bad. Better or worse. Worthy or unworthy.

It happens in so many ways. Consider birth order identity. I was born a second child, who eventually became a middle child, and such a birth order identity easily leads to becoming the forgotten child. You are not the eldest, whose right to exist is unquestioned because they were there before you, and they were lavished with a loving attention that was undivided; but now you come upon the scene, and you are desperate to divide that loving attention so you can get some for yourself. You want in on that love. But you must work to get it.

It’s called “sibling rivalry.”

Same basic situation with the youngest child. You are not the youngest, thus you are not the more vulnerable one, or the cutest, and therefore you are not the one on whom love is easily lavished.

Again, you’ve got to work to get noticed.

Our Unitarian Universalist First Principle of Inherent worth and dignity? Inherent, meaning “unconditional,” meaning “endless,” meaning “infinite”? Makes no sense to a middle child.

Made no sense to me.

We all have our stories of growing up. I offer mine to get you thinking about yours.

Besides racial and gender and ability and birth-order identities, consider how we are born into certain groups. We are born into families that are rich or middle-class or poor, and we are judged accordingly. We are born into single-parent families or two-parent families, and we are judged. Families that are Christian or Muslim or Jewish or Unitarian Universalist, and we are judged.

All these identities trigger social judgment, as better or worse. Judgments conflict too, depending on which part of society you’re talking about.

And then we grow older. Interests and talents are revealed, and they become identities that trigger judgments of bad or good. So does sexual orientation, and society definitely gives a person feedback about that. We are temporarily-abled until in some way we are not, and then we feel the sting of ableism. Our bodies grow into their adult shapes and we are revealed as tall or short, as skinny or middling or fat, as ugly or beautiful—and every identity word I am using here just oozes with judgmentalism.

Good or bad. Better or worse. Worthy or unworthy.

Judgmentalism, I am saying, is a fundamental condition of human finitude.

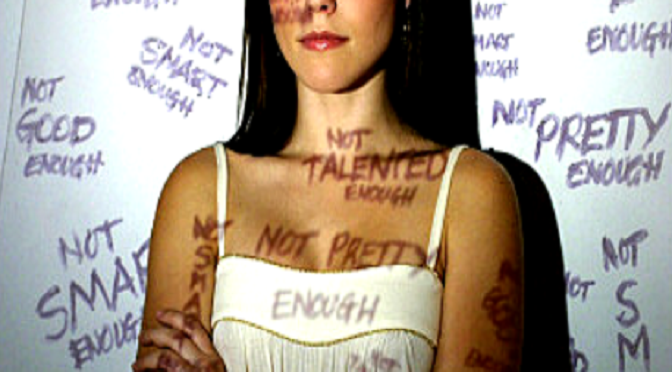

Judgmentalism fundamentally limits us. There is, in fact, so much emphasis on the judged identities that make us up, that it can seem we are nothing but our identities, and therefore we are nothing but beings who are judged. Our entire being is encompassed by judgment.

The whole social process is so ruthless and all-encompassing that, very soon in our lives, we internalize the judgmentalism—perhaps in a Stockholm-syndrome sort of way. The judgment coming at us from the outside world becomes a sub-personality within, a voice inside our very own heads that takes on independence and comes and goes as it will. Call it the Judger. The Judger judges everything. The Judger is like that crazed monkey with a baseball bat, in a tiny room full of delicate and beautiful glass sculptures, smashing every which way.

Good! Bad! Better! Worse! Worthy! Unworthy!

If we Unitarian Universalists happen to be white, or to be middle- or upper-class, the Judger at times gives voice to our unconscious racism and classism, as it smashes away at the people we encounter in the outside world. Inevitably, this happens, and we can be so shocked. We thought we were nicer than that. But it just means we are not sufficiently aware of the socialization process that takes a tiny human baby and gets it up to speed to play its part in the game of society, even at times against its will.

The game of society is to be judged, and to judge.

I believe that human fragility and vulnerability to pain and death are behind all of it. This gives birth to fear and to greed, and these metastasize into hatred. They are fiery forces, and they are unleashed through judgmentalism. They surge within the judgmentalism we feel towards others. But first and foremost, such fiery forces have been unleashed upon each of us. We have felt the full blast of fear and greed and hatred ourselves. This is the insight to hold on to. Judging others, then, becomes like a release valve. Judging others momentarily takes the pressure off of ourselves. We are choking on the hate of a hater that was put inside us which we did not knowingly choose.

A moment just to breathe means so much.

When you’ve been abused, it can feel like sweet relief to abuse others.

One day, I found myself back in yoga class and back on my yoga mat, which represents my commitment to being curious about my inner experience. I was moving from one pose to another, and, soon enough, the crazed monkey with his baseball bat started to smash away, and, like a broken record, the Judger’s voice was again comparing my yoga poses to those of others, telling me I was so much better–and then again came shame for doing this, and all of a sudden I heard the Judger’s harsh voice in my head judging me….

But this time, the Judger got interrupted. A wave of compassion came upon me. A wave, a wave, a wave. In that moment, I saw how my judgmentalism of others only expressed how my own soul had been crushed. It was only evidence of bad things that had been done unto me. My judgmentalism of others (beyond the mat too, trained on any and all identities that the others I encountered may possess) was simply the cry of my soul that had only wanted to be loved unconditionally and to be treated as if he had inherent worth and dignity without regard to any specific identities—and this had not happened.

From out of my judgment-filled human finitude, I have always longed to touch and be touched by the Infinite, which is unconditional Love.

My mat to me, in that moment, was a truly sacred space.

Out of my judgment-filled human finitude, I discovered the inkling of an identity that has nothing to do with judgment and everything to do with Love. And, from that point on, moving forward, I knew that I could not fully and freely live any of the smaller identities that society sorts me into and judges me by unless I was, in some simultaneous sense, always also dwelling in Love. If I can live within the larger infinite Love that my Unitarian Universalism affirms when it speaks of my worth and dignity as “inherent”—if I can steadily see the world from that perspective—then I can bring compassion to every person I meet whose judgmentalism is but evidence of how deeply they themselves have felt judged and how fear and greed and hatred have damaged them and damaged us all.

That’s the main thing. Being able to bring compassion.

Following all these insights, sometime later, I fell into a moment of quiet, and a memory came to mind. The memory was of something I’d read about Malcolm X. A deep moment of realization of his own in a context that, on the surface, seems entirely different.

But it’s not.

Malcolm X, you may know, was and is a powerful, prophetic Black voice raised against the sort of judgmentalism known as racism. He was assassinated in 1965, when he was just 40. The story of his I have to tell happened just months before his tragic death.

Malcolm X had been a key leader of the Nation of Islam, which, writes Pierre Tristam in ThoughtCo., was “an odd cult whose principles of racial hatred and separatism, and whose strange beliefs about whites being a genetically engineered race of ‘devils,’ stood in contrast with Islam’s more orthodox teachings.” Malcolm eventually became disillusioned with the Nation’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, and he realized that authentic Islam was a different thing entirely than what he’d been teaching.

And so, he went on a pilgrimage to Mecca, which is the destination of every pious Muslim at least once in life. From America, Malcolm first traveled to Cairo, the Egypt capital, then to Jeddha, the Saudi city. Muslims there already knew who he was. As Malcolm writes in his Autobiography, “They were aware of the yardstick that I was using to measure everything—that to me the earth’s most explosive and pernicious evil is racism, the inability of God’s creatures to live as One, especially in the Western world.”

When Malcolm finally arrived in Mecca, his mind was blown. “My vocabulary,” he says, “cannot describe the new mosque [in Mecca] that was being built around the Ka’aba.” It was “a huge black stone house in the middle of the Grand Mosque. It was being circumambulated by thousands upon thousands of praying pilgrims, both sexes, and every size, shape, color, and race in the world.” Malcolm continues, “My feeling here in the House of God was numbness. My mutawwif (religious guide) led me in the crowd of praying, chanting pilgrims, moving seven times around the Ka’aba. Some were bent and wizened with age; it was a sight that stamped itself on the brain.”

“In my thirty-nine years on this earth,” says Malcolm, “the Holy City of Mecca had been the first time I had ever stood before the Creator of All and felt like a complete human being.”

And that’s from Malcolm’s Autobiography. In America, he did not feel like a complete human being. From the beginning of his days, as is true of all of us, society sorted him; but because he was Black and he was a man, the sorting he endured was painful and disfiguring in a way that non-Blacks can never understand.

Is it so strange, for someone judged because of the color of his skin and nothing else, to think that whites must be a genetically engineered race of devils, as the Nation of Islam taught?

Is it so strange?

But authentic Islam became a place for him to dwell within, and to really see. To really witness. How God’s creatures might live as One, as opposed to the creatures of society who cannot possibly live as One because judgmentalism divides them into good or bad, better or worse, worthy or unworthy.

I stood upon my yoga mat to see this, and Malcolm stood before the Ka’aba and saw it circumambulated by thousands upon thousands of praying pilgrims, both sexes, and every size, shape, color, and race in the world, and his feeling there in the House of God, he says, was “numbness.” It blew his finite mind.

For the first time, right then, he felt like a complete human being.

That’s really what I’m talking about today. How to feel like complete human beings, whoever we are, whatever our particular collection of identities happens to be.

Soon, Martin would write a letter to a friend in New York, and the letter was published May 8, 1964 by the New York Times. In it he says, “There are Muslims of all colors and ranks here in Mecca from all parts of this earth.” “During the past seven days of this holy pilgrimage … I have eaten from the same plate, drank from the same glass, slept on the same bed or rug, while praying to the same God—not only with some of this earth’s most powerful kings, cabinet members, potentates and other forms of political and religious rulers —but also with fellow‐Muslims whose skin was the whitest of white, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, and whose hair was the blondest of blond—yet it was the first time in my life that I didn’t see them as ‘white’ men. I could look into their faces and see that these didn’t regard themselves as ‘white.’” “Their belief in the Oneness of God (Allah) had actually removed the ‘white’ from their minds, which automatically affected their attitude and behavior toward people of other colors. Their belief in the Oneness of God has actually made them so different from American whites, their outer physical characteristics played no part at all in my mind during all my close associations with them.”

That’s Malcolm’s letter—an excerpt of the full thing. The part that really stands out for me is when he speaks about the “white” being removed from people’s minds—whiteness being the judgmentalism that automatically translates into seeing non-whites as bad, as worse than, as unworthy.

We could equally speak of the “male” in people’s minds, or the “straight,” or the “able,” or the “middle-class,” and so on. Forms of judgmentalism that have been put in people’s minds by a society following its own value agenda and wanting to maintain its ancient ruthless game.

Malcolm came away from his pilgrimage to Mecca affirming that belief in the Oneness of God (which to him meant belief in Islam) was the power that could help every believing individual to dwell in Infinite Love even as, simultaneously, they lived as finite human beings bearing finite identities of race and class and gender and all the others. Again, the need to balance an Infinite identity with finite identities is a matter of antidoting the judgmentalism. It’s a matter of taking away the baseball bat from the crazed monkey of the Judger within. The Judger within starts up, and he gets neutralized by the wave of compassion that comes pouring in.

This is Love witnessing the abuse that’s behind all the judgmentalism.

This is Love empowering us to stop playing the judgmentalism game, and to see all people as Children of God.

I am not a Muslim. I don’t believe in the same sort of God that Malcolm believed in. But I do believe that we ended up in the same place. His pilgrimage experience to Mecca took him, I believe, to the same place that my revelation upon my yoga mat took me. That we don’t have to experience others and ourselves as purely finite beings, completely bounded by judgmentalism, nothing but a collection of judged identities, and relating to others through judgmentalism. Yes it’s true: as long as we live in this world, all our finite identities will remain. No one can stop being white or Black or cis-gender or trans-gender or male or female or intersex and on and on. But that’s not all of who we are. We can also and at the same time live as Children of God. We can see ourselves and others from that standpoint. And energy flows from that. Compassion that is divine flows from that. Compassion that disrupts the vicious judgmentalism game.

I will close with a few specific insights about what it means to live from an identity of Love, which is infinite.

The first is that right and wrong are not thereby vanquished. Right and wrong remain. Racism is wrong. Sexism is wrong. Abuse of any kind is just wrong. Yes, abusiveness ultimately comes from being abused first. It comes from being a tiny baby growing up in a society that abuses it through ruthless judgmentalism as the way to preparing that baby to play the game of human life. The abused abuse. But: abuse itself is wrong, so it must be stopped, and abusers must be held accountable. Compassion, however, says that abusers must never be treated like monsters. Holding abusers accountable must involve firmness but kindness.

Self-love, furthermore, tells us to stop returning to the line of fire, and get someplace safe. Because you love yourself.

And now a second insight about living from an infinite identity of Love, which is related to the first: it’s about affirming the Universalist idea that people’s actions are always motivated by the aim of doing what’s good and right—but as people conceive of what is good and right. They may be terribly confused about that, however, and so they act in ways that go very contrary to their best interests and those of others. So, of people who are confused, the question becomes, What got you there? What experiences have led you to think that?

Say that you are having a Facebook chat with someone about politics. They say something that, to your mind, is egregious. Don’t flame them. Don’t write them off as a monster. They are a Child of God. And you are living from your Child of God identity if you say back to them, Huh. That has not been my experience. Tell me your experience. Pay attention. Get on your yoga mat, and get more curious.

A third and final insight. When we are living from a Child of God identity, which is Love, which is infinite, we see others and ourselves as true Mysteries. Each of us is fighting a hard battle, the extent of which is truly unknown. You may think you know others, or yourself, and therefore you may think that the Judger voice within you speaks truly. But that Judger voice is finite, fashioned out of the fires of fear and greed and hate, fashioned out of the need of society to reproduce its values game, and it will never honor the Love in you and the full extent of who you are. It will never honor the Love in others and the full extent of who they are. It can’t. This is why I commend the phrase “child of God” even to those of us who don’t believe in God. Because Everyone’s challenge, atheist or not, is unconsciously falling into the trap of thinking that we are God-like infallible in our opinions. But our opinions are not God-like infallible. About others. About ourselves.

We actually don’t know squat about others, or ourselves.

To call yourself a Child of God is to acknowledge this finitude of understanding, but it is also and at the same time to affirm that you belong to the Infinite. You belong to Love. That there are depths in you that you may never know. That there is a goodness and wisdom in you that right now you might not be feeling. But just because you’re not feeling it right now, doesn’t mean it’s not there.

Maybe you would feel it, if you got on a yoga mat.

Maybe you would feel it, if you took a pilgrimage to Mecca, as Malcolm did, and saw what he saw.

Maybe there is a way to Compassion for you that’s not about a yoga mat or Mecca, but it’s something else.

Find it. Don’t allow yourself to be nothing but a pawn in society’s game. Free your mind. Don’t allow yourself to bound completely by judgmentalism and all the small identities arising out of judgmentalism.

All your limited human identities are you. But you are also more than that. Always.

You are also Love.

You are also a Child of God.

You are.

You are.