“The unexamined life is not worth living.” A man named Socrates said that long, long ago.

Do you believe it? That we diminish ourselves to the degree that we are apathetic about the truth, or that unconscious biases dictate how we see the world, or that we have a habit of confusing appearances with reality?

Many years ago, my 23 year-old-self

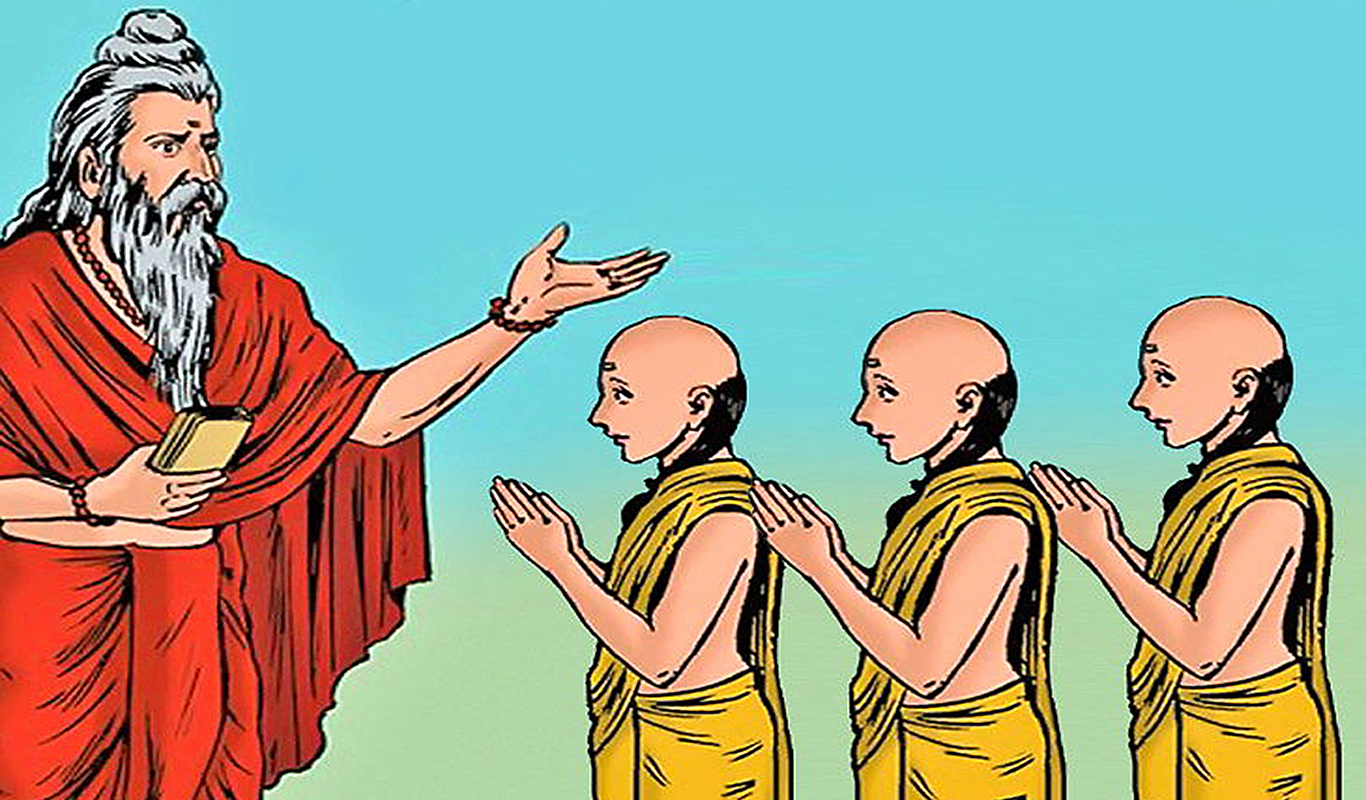

was in graduate school in philosophy because I believed people are indeed diminished unless we examine ourselves. Socrates was one of my all-time heroes. And not just Socrates. Thanks to the local Half-Price Books, I was reading stuff that appeared nowhere in any of my grad school course syllabi–this was extracurricular reading–and a lot of it was on Taoism and Hinduism and Buddhism. Stories like the following sparked my moral and spiritual imagination:

The guru sat in meditation on the riverbank when a disciple bent down to place two enormously expensive pearls at his feet, as a token of reverence and devotion. The guru opened his eyes, took up one of the pearls, but held it so carelessly that it slipped out of his hand and rolled down the bank into the river. This horrified the disciple, who plunged in after the pearl, but though he dived in again and again till late evening, he had no luck. Finally, wet and exhausted, he pulled himself out of the river, went to where the guru was sitting in meditation, and disturbed him. “You saw where it fell. Show me the spot so I can get it back for you.” The guru opened his eyes, reached for the other pearl, tossed it into the river, and said, “It fell in right about there!”

That’s the story. Now, consider the disciple’s attachment to the pearls. He cared too much about those pearls! The result being: suffering! Attachment to material things is a game people play, which causes suffering. And what about all the other games people play? I am thinking in particular about this game: how too many people dismiss climate change as a mere political thing, a manifestation of “wokism,” despite its thorough scientific backing and despite the undeniable hard feedback of wildfires in Canada & Hawaii as well as July having been the hottest month in recorded history–hotter even than June which had itself been the hottest month in recorded history, and so on….

The games people play, causing suffering. But the story about the guru and disciple also leads us to wonder: must suffering be our human fate? Is it possible to stop being our own worst enemy, and to become spiritually free?

I read this story when I was 23, and I wanted to know: could I grow to become less like the disciple and more like the guru? Could I?

Graduate school for me was more than 30 years ago, but the intense desire for greater wisdom has remained. Though by now I have made peace with the idea that the inner disciple will always be a part of me. It’s not something that can be eradicated. But may there be more moments when my inner guru can bring compassion to my inner disciple. May there be more moments when I can honor the anxiety or the fear or the confusion of my inner disciple without equating all of myself with that, and being ruled by it.

Not self-ignorance, but self-knowledge and spiritual freedom.

This is central to my ministry.

And how is it with your soul these days? Do you join me, in the thirst for wisdom? The quest for an examined life?

This quest for the examined life starts, I believe, with a sober and honest reckoning with traumatic experience. The experience of trauma is a human universal, with many sources. Let’s take a closer look.

One source of trauma is evolution itself. How the bloody and messy story of the struggle of our biological species to survive is written into our brain and body structures. As psychiatrist Russ Harris puts it, “Our minds evolved to help us survive in a world fraught with danger. […] The number one priority of the primitive human mind was to look out for anything that might harm you—and avoid it. The primitive human mind was basically a ‘don’t get killed’ device.”

In other words, evolution has tuned our minds towards the negative. Negativity is hardwired in us. Saber-tooth tiger threats—which our ancestors were right to be constantly vigilant about—are long gone, but we did not drop the constant vigilance habit. Not at all. Like Mark Twain says, “I’ve had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.”

Thank you, evolution.

Evolution has also taught us to be wary of exclusion from the group. Group membership to our ancestors meant safety, and deep down that knowing remains. So, today, we can be constantly worried about not fitting in, or making a fool of ourselves, or doing something that might get us rejected. Our minds are busy comparing ourselves with others: Am I too thin? Too fat? Too tall? Not tall enough? The mandate to fit in can be felt so overwhelmingly that a person becomes willing to play the game of rejecting all scientific evidence and even the evidence of their own eyes to stay loyal to the dictates of their tribe.

Evolution is the foundation of such a game! “Evolution,” says psychiatrist Russ Harris, “has shaped our brains so that we are hardwired to suffer psychologically: to compare, to evaluate, and criticize ourselves, to focus on what we’re lacking, to rapidly become dissatisfied with what we have, and to imagine all sorts of frightening scenarios, most of which will never happen.”

And then he says: “No wonder humans find it hard to be happy!”

No wonder any of us might search for some kind of guru, to seek release!

And this is only one flavor of trauma that is inflicted upon us.

Another is the sort of trauma that is personal and happens during the course of one’s living. Being born with juvenile diabetes, for example, as was the case with David (see the story, below). Other examples might include growing up poor, enduring a pandemic, or experiencing dislocation and homelessness because your city was burned to the ground by wildfires or warfare. And then there is abuse from someone you trusted–it is so terrible–which is often because the abuser suffered the same thing when younger, and here is a case of trauma breeding more trauma, passing it down the generations.

Yet a third kind of trauma comes from being born into an identity that society marginalizes and oppresses. So is being born into an identity that society privileges. It’s never about you personally. You, personally, deserve none of the prejudice and none of the privilege. But you get it anyway, for reasons that are completely arbitrary. Color of your skin. Structure of your plumbing. Direction of your sexual desire. Shape of your body! The impersonal social system injects bias in us, injects “isms” and thereby distorts character and diminishes humanity, and the result is a world of haves and have nots, and that is a world full of trauma, I guarantee you.

Call this sort of trauma “systemic.”

And there’s still more kinds. All of them feed the inner disciple, who is thereby made spiritually unfree and full of suffering, and therefore, the inner guru has its work cut out for it.

There’s that old saying: “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle.”

What do you think?

And now a fourth and final kind of trauma for us to consider here: the developmental traumas that are part of everyone’s hero journey of life. A developmental psychologist like Erik Erikson tells us that, from birth to death, there are eight “psychosocial” crises a person will inevitably face when they get to be of a certain age. One of the big take-aways here is that a person’s character is inextricably interwoven with how they handle each crisis. Crisis is how character grows. We are made by crisis. There is indeed a hero in each and everyone of us, but that hero can’t emerge unless: crisis.

It’s always struck me as funny when people talk about dreams. “Oh, it was dreamy!” “It was a dream come true!” Really? I don’t know about your night-time dreams, but my night-time dreams are full of problems to solve. I’m always getting lost. I can’t find my car keys. I’m showing up on Sunday morning to preach but I’ve forgotten my manuscript, or I’m naked. And perhaps it’s just not about me. “Researchers estimate that people experience about 1,700 threatening REM dream episodes per year, or almost 5 per night. Projected over a 70 year life-span, the average person would suffer through about 60,000 threatening REM dreams featuring almost 120,000 distinct threats.” This bit of data is from a book called The Storytelling Animal, and its main contention is that we are storytelling animals and that the most compelling stories for us are stories of facing crisis. That our deepest humanity shines in that!

So we come to what I like to call the allegory of coffee beans. You can’t know the good thing that comes from coffee beans until you bring crisis to them: roast them, grind them up, pour boiling water over them. Only then does the coffee come, and the enjoyment of it.

Coffee, Coffee, Coffee, Praise the strength of coffee.

Early in the morn we rise with thoughts of only thee.

Served fresh or reheated, fatigue by thee defeated,

Brewed black by perk or drip or instantly.

Remember this when you find yourself afraid about the state of our world. Crisis brings the hero out of us. There’s a hero in you and in me that’s more than up to the challenge. Your sense of fear is your sense of a call to find a way to make a difference–to find the hero path that’s uniquely yours.

Trauma is the trigger. No less than four dimensions of it: evolution-based, systemic, personal, developmental. The quest for the examined life begins with an honest acknowledgement of this.

And then the quest moves on to a second acknowledgement, which is a distinction: that, on the one hand, you have the pains of life, but on the other hand, you have spiritual suffering. A great gift coming from Buddhism and other world wisdom traditions is the insight that physical distress and physical pain are one thing but how people show up to that, what stories people tell themselves about it, where people sink the anchor of the their fundamental sense of safety and vitality—ah, that is another thing entirely, and it makes all the difference.

I mentioned earlier how, as a young man in grad school, I did a lot of extracurricular reading–and one of my favorite finds was a book entitled Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: a book that, story after story, helped me to see the big difference between the mere fact of pain and the variety of possible spiritual responses, some of which intensify suffering but others of which reduce it. Here’s one of my favorite Zen Flesh, Zen Bones stories:

Ryokan, a Zen master, lived the simplest kind of life in a little hut at the foot of a mountain. One evening a thief visited the hut, only to discover there was nothing in it to steal.

Ryokan returned and caught him. “You may have come a long way to visit me,” he told the prowler, “and you should not return empty-handed. Please take my clothes as a gift.”

The thief was bewildered. He took the clothes and slunk away.

Ryokan sat naked, watching the moon. “Poor fellow,” he mused, “I wish I could give him this beautiful moon.”

That’s the story. Clearly, Ryokan the Zen Master anchored his safety in something very different from possessions. The purpose of his life was something very different from “what’s in it for me.” He experienced something we would all agree was physically jarring, but the result to him was not spiritual suffering. Not at all.

Which is in stark contrast to the thief, who is in a place of spiritual suffering, deeply so, to do what he was doing in the first place. Poverty traumatized the thief, stole so much from him, and he is stealing back what he feels he’s owed. It’s all unfair, from beginning to end. So why should he care about the unfair pain he inflicts on others? Stealing, for him, is like a survival strategy. Besides being the means of his survival, it is a way of protesting the unfairness of a society that allows for and enables poverty, and it is a way of shoring up a sense of personal dignity and value.

Do you get that language of “survival strategy”? It’s what we spiritual beings having a human experience do to cope with trauma. Trauma jars us, and because we don’t yet know that our true safety can be anchored in something untouchable by the hard knocks of life, we interpret what is happening to mean that we are in deep danger; we must resort to some exaggerated and artificial game to protect ourselves. In my case, I learned to protect myself in the face of my deeply mentally ill and abusive mother by adopting a tripartite survival strategy: (1) perfectionism, (2) self-abandonment so that I could give my all to managing the borderline personality disorder chaos of my mother, and (3) self-discipline through shaming—so that when a personal desire or a need did pop up and threaten to create conflict with my family, I’d push it down with a vicious shot of shame.

Shame was the cattle prod I learned to use to keep myself in line.

Does this speak to anyone here? Is this a part of your story too?

It worked! I survived. But the thing about survival strategies is that there gets to be a time when you discover that it’s bringing you way more unhappiness than happiness. That’s it’s really not working anymore. It’s just as the mystic and poet Rumi once said: “Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.” The Love is and has always been there, deep inside. That’s the inner guru! But to survive chaos, you build the walls. Then the day comes when you’ve forgotten all about the Love deep inside, and you’re anxiously grasping for anything external that seems like it can give you the Love you’re missing…..

Or, maybe a character like the Zen Master comes into your life, and you just do your survival strategy thing, whatever it happens to be, and his response to you in no way plays by the rules of your game—you’re playing a finite game and they’re playing an infinite game—and you are bewildered, you slink away, and maybe it gets you to wondering if, perhaps, your life could be different than you’d ever imagined….

The title of this sermon is “Four Noble Truths” and by now we have covered the first and second.

The first is, “Life is suffering.”

The second is, “Suffering is caused by stuck behavior patterns which we developed to survive chaotic, cruel, nonempathic environments.”

Which leads to the third: “Life doesn’t have to be this way.”

When I was six or so, I hadn’t lost conscious connection with my inner core of Love yet. At six years old I knew with inexplicable certainty, in a part of myself untouched by the rest of my life, that suffering and despair don’t have to be the last word. Growing up in Northern Alberta, in Canada, I lived by a river called Peace River, and it spoke to me.

It spoke to me of irrepressible Life at the core of all beings that is deeper than the deepest trauma. There is a Peace River at the heart’s core of everything and it is a pressure to push through all blockages and walls and to open up a way to larger realities in life, of reverence, gratitude, forgiveness, compassion, justice, peace….

When we seek it out—or when it seeks for us. That’s the truly incredible part. When the Love deep within seeks us. Think back to the story about David (see below). David suffers primarily because he reduces all that he is to the single fact of his juvenile diabetes. But one night he has a dream. He dreams of a statue of the Buddha. David wasn’t a religious person in a traditional sense; he didn’t know much about Buddhism at all. It’s just that something wise within him felt a kinship with the Buddha image and used it to say, “Here I am!” It was the inner Peace River reaching out to him, using the Buddha image. The Wellness deep within was making itself known…

This is what I mean when I say that grace is real.

The dream told him a better, more honest story that he was telling himself. It told him that his physical sickness was nothing to dismiss. It was like a steel grey dagger! It hurts! It’s thrown into the heart of something innocent. He was innocent. None of that New Age crap idea that says if you get cancer then your thoughts must not have been positive enough, you must have done something to cause it. No way! Cancer happens. Bad stuff happens. In the dream, David’s response to the dagger thrown at the innocent Buddha was like his response in real life: anguish, rage. But the dream goes on from there. In the dream, the Buddha statue changed in a way that echoed the countercultural wisdom of a Zen Master. It just grew. The statue just grew bigger and bigger.

Meaning: that while our egos play out their survival strategies and rage and curse at adversity, the inner Buddha in every one of us wants us to respond in a very different way: TO GROW. It’s not that the physical pain of life is ever taken away. The physical daggers–at least four different kinds of them, as we saw from earlier—they hurt. They hurt terribly. But no matter what kind of dagger is thrown, our souls as a response can grow, our vision of ourselves and what the world means can grow. In turn, it means that every dagger, finally, assumes its proper place and proportion in the scheme of things. The inner Buddha will always be larger than any pain. Tap into that largeness, that spaciousness and size, and spiritual suffering decreases. Compassion and peace increase. Power to show up, to do one’s part, and then to let go—that power becomes ours. All the tension within us, the way we hold our bodies as if we’re just waiting for life to ambush us at any moment—we can let that go. We can live in this world and say Yes to it. Accept all that it brings, all the ups and downs.

And our hearts will soften, our eyes will fill with tears.

Love will flow, like a Peace River from deep within our hearts.

The Four Noble Truths was the Buddha’s very first sermon. I’m wanting to start our 2023-2024 program year with it so that we here at West Shore begin in a spiritually grounded way, with clear intentions for growth. Number 1: “Life is suffering.” Number 2: “Suffering is caused by stuck behavior patterns which we developed to survive chaotic and cruel environments.” Number 3: “Life doesn’t have to be this way.”

And now we turn to Noble Truth Number 4. For the Buddha, the Fourth Noble Truth essentially says that suffering can be healed if a person practices the spiritual disciplines of the Eightfold Path: Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. Here’s what can turn the thief of the Zen Flesh, Zen Bones story into a Zen Master. Here’s what can help to strengthen the inner guru. Here’s how you practice what Socrates spoke of, when he spoke of examining oneself.

Check it out. See the “Deep Dive” resources in your order of service to learn more. All I will say here, as my sermon comes to a close, is to affirm the importance of spiritual balance. Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. Yes and yes and yes. All of this good spiritual work. But never forget that one’s personal efforts only go so far. Sometimes we just get stuck. No one blooms all year round! No one blooms all year round! Sometimes we just get stuck. Sometimes we just get confused. Or tired. Or moody. Or whatever.

Even so–even so: grace is real. We are sought after. It’s not all on us. Spiritual growth is not a one-sided sort of thing.

Islam’s Mohammed put it like this when he spoke the words of Allah. Speaking for Allah, he said, “Take one step towards me and I will take ten steps towards you. Walk towards me and I will run towards you.” That is grace. Now, as Unitarian Universalists, we can wonder: is grace about God? Is it? But grace itself–that’s real. Often it can be as simple as a teacher who comes into your life whose free gift to you is to help you see the world differently. It’s one reason why I love our RE teachers here at West Shore. They are literally agents of grace.

But also consider something called a “glimmer.” A “glimmer” is the opposite of a trigger. It’s like a micro-moment that makes you happier, a little moment of awe, something that makes you feel hope even if just for a moment. Once you start looking for these gifts that are coming to you all the time, life can feel so much sweeter….

Sometimes, we are so deep in our suffering, that suffering is all we feel we are, and it seems no one can help. We are flailing about. But there is a Peace River already flowing in each of us, and that is the anchor of our true safety, and nothing external can diminish it. In such a time, don’t just do something–don’t redouble your efforts–just stand there. Be still. Practice wise silence. Let the clutter in your mind fall away. Allow your deep wisdom to find you. Allow yourself to be found.

Let the teachers come.

Let the glimmers come.

If God is real for you, let God come.

Know this best of all philosophies: At the core, you and I are all fundamentally Buddhas. There is a fundamental Peace River spiritual health at the core.

Even as you seek, you are sought after.

And, whatever steel gray knives have been thrown at you, or are being thrown at you, or will be thrown at you, don’t despair.

Know that’s the call to the hero in you.

The best revenge is to grow.

READING

Our story today comes from a real-life incident related to us by Rachel Naomi Remen, a medical doctor whose special focus is counseling those with chronic and terminal illness.

The story is about a teenager named David. David was diagnosed with juvenile diabetes two weeks after his seventeenth birthday. He responded to it with all the rage of a trapped animal. He flung himself against the limitations of his disease, refusing to hold to a diet, forgetting to take his insulin, and using his diabetes to hurt himself over and over. Fearing for his life, his parents insisted he come into therapy. He was reluctant, but he obeyed.

After six months of therapy, he had not made much progress. But then he had a dream that was so intense, he didn’t realize until later—–after he had woken up——that he had even been asleep. In his dream, David found himself sitting in an empty room without a ceiling, facing a small stone statue of the Buddha. He was not a religious person, so he didn’t know much about Buddhism. All he knew was that he had a feeling of kinship with the statue, perhaps because this Buddha was a young man—-not much older than himself.

The statue’s face was very still and peaceful, and it seemed to be listening to something deep within David. It had an odd effect on him. Alone in the room with it, David felt more and more at peace himself.

David experienced this unfamiliar sense of peace for a while when, without warning, a steel gray dagger was thrown from somewhere behind him. It buried itself deep within the Buddha’s heart. David was profoundly shocked. He felt betrayed by life, overwhelmed with feelings of despair and anguish. From his very depths, a single question emerged: “Why is life like this?”

And then the statue began to grow, and grow, and grow, so slowly at first that David was not sure it was really happening. But it was. This was the Buddha’s way of responding to the knife.

But its face remained unchanged, peaceful as ever. And though the Buddha grew, the steel gray knife did not change in size. As the Buddha grew larger, the knife eventually became a tiny gray speck on the breast of the enormous, smiling Buddha. Seeing this, David felt something release inside him. He could breathe again. He awoke with tears in his eyes.

Here ends the story.

Leave a comment